These AIS MOB devices can alert your yacht, and others close by, to a man overboard. Pip Hare tests a selection of the latest models and considers the search and rescue options

In a safety briefing for the double-handed Transat Jacques Vabre race, a French search and rescue pilot told us just how hard it is for a spotter plane to see a person in the water.

He pointed his finger at the audience of sailors and very firmly told us that we were the best chance our co-skipper had of being recovered after falling over the side and that we must ensure our counterparts were wearing the correct safety equipment when on deck. He also stressed how important it was that we both had tested and were aware of how to use our AIS locator devices.

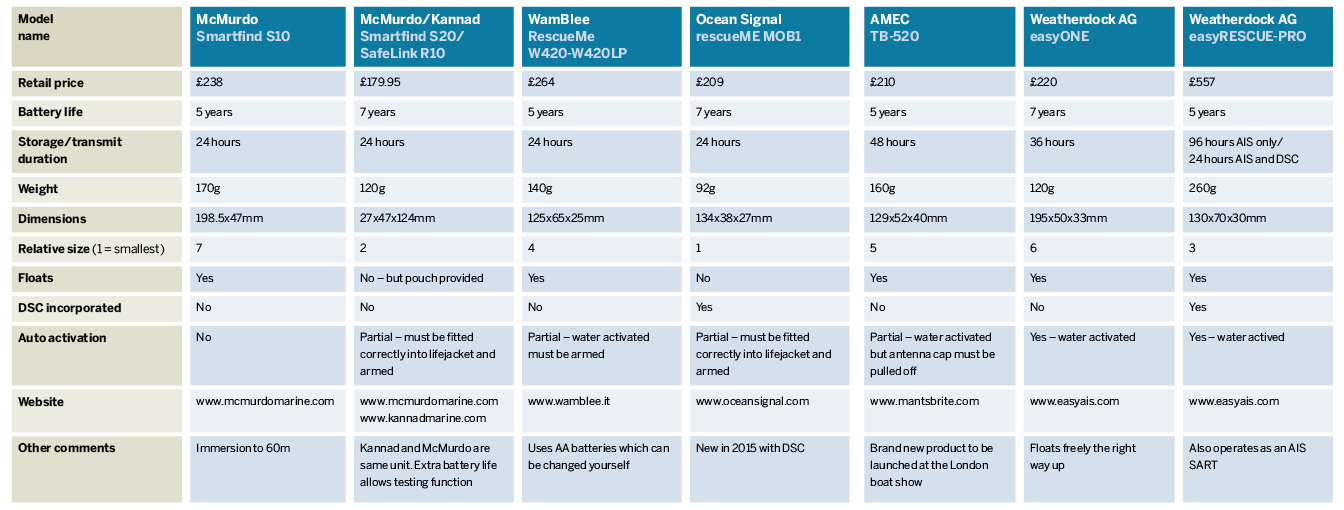

With the prevalence of these devices increasing and many sailors now making a choice between an AIS location device and a personal locator beacon, I gathered together seven AIS MOB devices and compared their key features to understand what each one could offer, how they perform and how AIS fits into the search and rescue safety package.

With the prevalence of these devices increasing and many sailors now making a choice between an AIS location device and a personal locator beacon, I gathered together seven AIS MOB devices and compared their key features to understand what each one could offer, how they perform and how AIS fits into the search and rescue safety package.

Who’s it for?

It is generally accepted that for those sailing alone a more traditional personal PLB EPIRB, which operates on 406MHz, remains your best chance of being found in an MOB situation. For the majority, however, who sail on a crewed yacht an AIS device, such as the ones we tested, allows both the mothership and nearby vessels to identify your exact location using an AIS set or chartplotter.

AIS MOB devices tested

McMurdo Smartfind S10

The first of its kind, produced in 2011, this was originally aimed at divers hence is waterproof to 60m. It has an integral antenna housed in the waterproof casing, which illuminates when the device is activated.

YW rating: 8/10

RRP: £238 / $310

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

McMurdo Smartfind S20/Kannad Safelink R10

These are the same units produced by the two Oriola brands. They are small, and offer automatic in-lifejacket activation. These are the current brand leaders in personal AIS devices.

YW rating: 8/10

RRP: £179.95

WamBlee RescueMe 420–LP

This water-activated unit is designed to fit inside a lifejacket. It has an antenna housed in plastic tubing that fits around the collar of the lifejacket and does not need deploying prior to activation.

YW rating: 7/10

RRP: £264

OceanSignal RescueMe MOB1

Despite being the smallest of all current models on the market, the RescueMe MOB1 also incorporates a DSC function. The device is designed to fit inside a lifejacket.

YW rating: 9/10

RRP: £209 / $299

AMEC TB-520

This is a new device produced in Taiwan that is due to be launched in January at the London Boat Show. It offers automatic activation and has bright LED lights in the housing, which flash the SOS message when the unit is activated.

YW rating: 7/10

RRP:£210

WeatherDock AG – easyONE

The easyONE is an entirely water-activated device that floats with its antenna facing up. It could be either kept in a pocket or tucked inside a lifejacket with no fitting or arming required.

YW rating: 8/10

RRP: £220

WeatherDock AG – easyRESCUEpro

This is the largest, heaviest and most expensive of all of the devices tested; the easyRESCUEpro can double as a liferaft SART, and incorporates a GMDSS-approved DSC alerting function.

The easyRESCUEpro does stand apart from the rest at £557, but this is down to its extra DSC functionality and ability to double up as a liferaft SART with extended battery transmission time.

YW rating: 7/10

RRP: £557

AIS MOB device fitting

All the devices fit inside a lifejacket, although some not quite as unobtrusively as others. Fitting options varied across the range, including belt loops, pouches or oral inflation tube clips.

All the oral inflation tube clips were firm and easy to fit, with the exception of the Wamblee, which uses an angular stainless steel bracket that I found fiddly. If choosing the Wamblee I feel the belt loop option is better; it comes with both.

The units with clips or belt loops can also be fitted inside a lifejacket to a suitable strop. Not all lifejackets will have these. Ocean Safety now includes a strop as standard in its Kru Sport Pro jackets, but it would be a good idea to look inside your lifejacket or talk to a service agent before taking up this option.

A small design feature that made a big difference was the addition of teeth on the McMurdo and Kannad belt clip. The teeth gripped the webbing strop firmly and kept the unit exactly in place even during automatic inflation. The clip without teeth on the AMEC unit, however, slid off the side of the bladder during activation.

The two Weatherdock and the McMurdo S10 devices are larger and can be tucked inside a lifejacket cover with the lanyard attached. They all fitted, but left bulky profiles and I definitely felt the weight of the easyRESCUEpro.

Belt loops and pouches enable a wearer to attach the devices outside the lifejacket. If attached at the waist or hip, however, they would be fully submerged if you fell in the water and unable to transmit. Units correctly fitted inside the lifejackets are already in the ideal position for transmission as soon as the jackets are inflated.

Not all the devices floated. Although the Kannad and McMurdo come with a floating pouch, this can only be used when the AIS device is dormant. Once transmitting, the GPS area must be kept clear so it cannot be put back in the pouch. The easyONE floats upright with the antenna pointing at the sky. This means that, however you carry it, it will always float to the surface and transmit. The AMEC floats, but not antenna up.

Automatic activation

There are two ways for devices to activate automatically: one is with water contact and the other is via a pull-string when the lifejacket itself goes off. For the test results I have labelled devices as partially automatic if they require arming to ensure activation.

The pull-to-activate mechanisms rely on a lanyard attached from device to lifejacket, which when put under tension by the bladder inflating, will pull away, releasing the antenna and activating the device.

Kannad, McMurdo, AMEC and Ocean Signal all use this system of activation. They recommend set up by an approved lifejacket service agent. Trial and error enabled me to find the right lanyard length; across the board the jackets needed to be firmly under pressure to get the devices to activate.

When jumping into the water wearing an auto-inflate lifejacket the results for the Kannad/McMurdo were impressive; by the time I had resurfaced, my lifejacket was inflated and the locator device was resting on top of the bladder, antenna pointing at the sky and LEDs flashing. The AMEC auto-activated well, but I had to reposition it to the top of the lifejacket bladder once in the water.

Water-activated devices rely on immersion to make an electrical connection across two contact points. The WamBlee and AMEC need arming to ensure automatic activation and both the Weatherdock units are fully automatic without arming.

The easyONE has a neat system using a dissolvable salt tablet to deploy the antenna. When tested in my sink, the force of the antenna escaping scattered bits of salt tablet half way across the room. It’s clever, but I wouldn’t recommend having it near your face during activation.

The easyONE has a neat system using a dissolvable salt tablet to deploy the antenna. When tested in my sink, the force of the antenna escaping scattered bits of salt tablet half way across the room. It’s clever, but I wouldn’t recommend having it near your face during activation.

Those of us who get regularly very wet when sailing might shy away from water-activated units. I am sure if accidentally activated inside your lifejacket there is little chance a signal would escape, however repeated activation may affect battery life.

The only device that cannot be automatically activated is the McMurdo S10.

A surprising range

I made several tests on the range of each device and in different circumstances and found little notable difference between units. Within the harbour, devices set off at water level were not detected at a range of half a mile from a receiving aerial at mast height. Along a cliff line this range was up to a mile, and over a sandy headland the signal was lost at two miles.

On open water the results for all sets were astoundingly good. I tested up to three-and-a-half miles with the AIS devices in the water and the receiving aerial at just over 14m high. On all occasions all sets continued to produce strong and regular updated information to the receiving AIS plotter at intervals of less than one minute.

Watching from my man overboard position with the devices at water level, the yacht with the receiver was no longer visible from two miles away.

I had expected to see some variance in the performance across the devices in this area, however all sets performed well enough to save your life. These tests were picked up by other passing vessels and also showed up on the marine traffic website.

‘All ships’ alerts

Two devices, easyRESCUEpro and MOB1 incorporate a DSC alerting function, which allows the unit to be paired to a mother radio set on board your vessel. Upon activation they automatically send a closed loop (unit to unit only) alert to the mother set detailing MOB information. Both units were straightforward to program and sent test DSC alerts.

The MOB1 can also send a manually activated ‘All ships’ DSC alert. The easyRESCUEpro offers a more comprehensive system: it first sends a closed loop alert to your mother ship. If this alert is acknowledged you will receive an acoustic signal from the AIS device. If, however, no acknowledgment is made within five minutes, then the device will automatically switch to an ‘All ships’ transmission, which will carry on until acknowledged by another vessel.

The easyRESCUEpro is a popular commercial and military choice. It is designed to be used both as a personal device and as an AIS SART for a liferaft. It is also the only unit able to receive a DSC acknowledgement, so manufacturer Weatherdock claims it is GMDSS (Global Maritime Distress and Safety System) compliant – which in plain English means it is the only one that is actually a recognised way of calling for help.

However, this is the heaviest and most expensive unit (more than double the price of the smaller devices tested).

Calling for help

You may notice I refer to the sets as AIS devices and not beacons. This subtle difference in name is important. A beacon is an internationally recognised means of signalling distress, whereas an AIS personal locator device is not. The beacon says: ‘I am here and I need your help’, the device just says: ‘I am here’.

Further to this fact, we must also consider who is going to notice when one of these devices goes off and what they actually see.

Since the launch of AIS locator devices in 2011, the rate of development of this product has been quite a bit faster than the infrastructure designed to support them.

All personal devices are identified by a unique ID that starts with ‘972’. When the AIS devices first came out AIS equipped chart plotters displayed them as vessels. The MOB symbol of a red circle with a red X inside came out a year or so later, and the specification for sets to make an audible alert is very recent.

Although manufacturers have been quick to incorporate new features into plotters there is no requirement for old AIS receivers or plotters to be upgraded to new software acknowledging the 972 symbol or the audible alert. It is down to the individual owner to decide whether to make these changes.

I found a range of results in my testing. Some older sets even with recent software updates are not able to display the MOB symbol. Not all sets, whether new or old, include the sentence MOB TEST when test mode is activated. And if the AIS receivers and chart plotters are different units, both may need software updates.

The answer to this is clear – if you are going to carry a personal AIS device you must always test it against the boat on which you are sailing to find out exactly what will be displayed on activation and if an audible alarm will be sounded.

As someone who sails regularly double-handed I consider the audible alarm function an essential component. If your AIS plotter is not able to produce an audible alarm then the DSC-capable AIS MOB devices from Ocean Signal and Weatherdock could provide an alternative alerting system. Wamblee also have a DSC model, the W460.

Therefore, although many vessels now carry AIS, it is not safe to assume that every vessel within range will see, understand or react to your MOB device. And as the most likely people to rescue you, it is essential your own crew are aware of the capabilities of your own device.

The rescue services’ response

In understanding the scope of AIS MOB devices it is also important to know how AIS is interpreted by the people who manage our coastline and our rescue services.

There is currently no requirement for HM Coastguard shore stations to receive alarms if an AIS device is activated. The coastguard uses AIS in its control rooms as a situational awareness tool, but its AIS software is not currently able to display the MOB symbol on receipt of a 972 AIS signal. On its screens, an AIS MOB device will show up as a coloured triangle like all other AIS-equipped vessels.

The RNLI is in the process of installing AIS on all of its lifeboats, however it envisages it will be three years before the crew and fleet are fully AIS-functional and trained.

Until then, the advice from both services is that ‘AIS is incorporated into search and rescue wherever possible, but the AIS location devices should be considered as part of a package of safety equipment and not solely relied upon. Don’t forget the traditional means of calling for help such as DSC if you wish to guarantee your call reaches the search and rescue authorities.’

Among the other people who definitely can see AIS devices are the various Vessel Traffic Services around the UK. I worked with Poole Harbour Commissioners during my testing and had a look in their control room.

Captain Brian Murphy, Poole’s harbour master, told me his VTS staff will report any AIS MOB alerts directly to the Coastguard. In many cases, particularly in estuaries and close to the land, VTS have greater AIS coverage than the coastguard, so are more likely to pick up alerts.

Conclusion

When choosing one of these AIS MOB devices over a 406 MHz beacon, you are consciously giving the responsibility of your rescue to your crew. Naturally they can alert the authorities as well as coming to your aid, however only when they notice you have gone.

There is much talk about combining a 406 MHz beacon with the AIS locator device. The sticking point here is that 406 MHz devices are not allowed to be automatically activated – so currently the two items cannot be easily combined.

Chris Hoffman, chairman of the Radio Technical Commission for Maritime Services (RTCM) in the US, told me that they are in the process of writing the first specification that will allow the combination of the two and that we may see these products on the market in the US in 2017. However, there are currently no plans for a European specification, so the timing of their introduction in the UK and Europe is unclear at present.

If you are waiting for the combination AIS/406 devices to make it onto the market before investing in an MOB alerting system, I would think again. Technology is moving on at pace and who knows what the world of tracking and communications will look like in four years’ time – all lifejackets may automatically come with tracking chips.

Today, if you sail regularly with crew on a vessel fitted with AIS, I have no doubt these small and brilliant devices might one day save your life.