Is foiling here to stay, or is it simply a spectacular means of making pro racers go fast? Matthew Sheahan looks into the rapid development of foils and asks what’s in it for us?

“There’s nothing new in what we’re trying to do with foiling America’s Cup boats,” says Land Rover BAR’s head of engineering, Dirk Kramers. “The Wright brothers would have understood the physics of an AC45f, they just wouldn’t have been able to build it.”

He has a point. The basic principles of lift, drag and flight have been known for over 100 years and if there’s one thing that the experts all agree on, it’s that nothing has changed in the physics. Yet the rapid growth of the new foiling watercraft generation has been one of the biggest modern breakthroughs in sailing.

Driven initially by the International Moth, boat speeds have more than doubled in one leap of technology. But apart from the speed, perhaps the most exciting aspect is that some of the technology involved is heading downstream towards the rest of us.

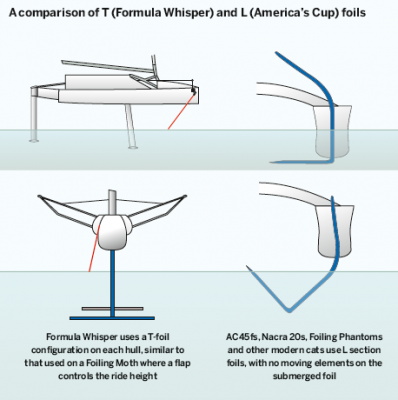

The Formula Whisper foiling catamaran, which we looked at in the August issue, is a good example of how the Moth’s T-foil configuration has helped to create a foiling boat that can be sailed by club sailors rather than pros.

Then there’s the plug-in foiling kit for the standard Laser that promises foiling for all aboard a stable, well-known platform.

At the other end of the scale the move to hydrofoils in the America’s Cup has led to a huge leap in performance since the last Cup match in San Francisco in 2013, with some of the top teams already hitting 30 knots upwind and well over 40 downwind with their 45ft development boats.

And while the teams all seem a little shy about stating how fast they expect to be going in 2017, no one will mock you if you suggest that 50 knots is possible.

Will the technology filter down?

So while there is plenty of development in foil technology in the racing side of the sport, there can be no doubt that it is the big budgets and large design teams made possible by the Cup world that are currently driving the foiling revolution.

But will the lessons learned from this hotbed of development filter down to the rest of us? And if so how?

There are plenty who believe that the answer is yes, but point to aspects of the new technology other than pure speed as being the future benefits. Although the focus for Cup spectators has been the speed, control is where the biggest steps have been made recently: control of the foils to provide smooth, stable flight; control of the boat through tacks and gybes as the entire boat continues to fly above the water’s surface; and control of speed changes, heading and trim without performing a dramatic bows-up wheelie at the leeward mark. Indeed, it is mastering control that many experts believe will win the America’s Cup in 2017.

© ACEA / Photo John von Seeburg

But before we get carried away with the idea that the Cup boats will provide all the answers, it is important to consider that there are other ways to exploit the benefits of high- performance foils. One person who knows this well is world speed record holder Paul Larsen.

“When you’re looking at how foils can increase performance, it is the relationship between power and drag that defines top speed,” he says. “If you opt to reduce the drag by lifting the boat out of the water you can increase speed. Alternatively, you can increase speed by keeping the drag the same and increasing the power generated by the foil.”

It is this latter approach that was one of the cornerstones of Larsen’s success with Sailrocket 2. When he set the new outright speed record of 65.45 knots there was not much of his bright orange machine touching the water other than the hooked foil to windward and the T-foil rudder at the stern. The key was to grip the water efficiently and use the main foil to generate power rather than using it to lift the boat above the surface.

“If you keep reducing drag you end up running out of righting moment,” he explains. “For example, in high performance dinghies like the 49er you end up having to bear away further in the breeze or twin trapeze deeper downwind to stay upright. After that you need heavier crew just to generate more righting moment for more power. It is why the foiling Moth and A Class cat classes, among others, are starting to see heavier sailors aboard.”

It’s not all about speed

But even the sailing world’s fastest man doesn’t think that outright speed is necessarily the answer. His view of the future for offshore foils envisages faster ocean passages, not just for stripped-out, record-breaking machines, but for vessels carrying a payload.

Photo: Helena Darvelid

“It’s like jets on commercial aircraft,” he says. “Sure we’ve had the technology to travel supersonic for some time, but the biggest benefit to most of us is being able to fly above the weather. This has resulted in reliable schedules and efficient travel. The same could be possible with modern offshore foils that allow us to travel fast enough never to have to sail in bad weather.”

Others have also seen the benefit of using a foil to generate more power. Most recently some of the latest IMOCA 60 boats have fitted wild-looking foils shaped like giant sabres with winglets that protrude from their topsides like the spurs on the wheels of a Roman chariot.

With these boats the thinking is that, instead of lifting the boats out of the water, foils are used to increase power by generating more righting moment. But problems aboard some of the IMOCAs during the recent Transat Jacques Vabre race suggest that maybe these foils are generating more power than teams expected and have overloaded the structure elsewhere in the boat. Others are concerned that the additional righting moment will overload the one-design mast that the class has now adopted.

The Dynamic Stability System (DSS)

But amid the rapid development in grand-prix racing classes, there is one system that is far from experimental. The Dynamic Stability System (DSS) has been increasing righting moment and boat speed successfully – while also creating a better motion – for ten years across a wide range of boat types and sizes.

The system is based on a horizontal foil that is deployed on the leeward side. As the boat picks up speed, the foil produces vertical lift, which increases the righting moment of the boat and hence power. However, the system also serves to dampen down the pitching moment, making for a more comfortable ride.

“There is no question that DSS can not only improve performance, but it can have a big effect on the motion of the boat as well,” says Gordon Kay of DSS. “And it’s not just performance boats that benefit. Any offshore sailing where reaching and running is important can benefit from this system, so for trips like the ARC rally it’s ideal.”

Since Team New Zealand managed to get its 72ft Cup boat up on foils making cats fly has appeared easy. Suddenly, a rush of classes that could fly appeared on the scene: boats such as the Flying Phantom, the Nacra 20f, the A Class and

C Class cats and the GC32, to name just a few. Last year even a 40ft performance cruising cat strutted around on foils as Gunboat’s G4 took to the air early in 2015.

However, keeping these cats in stable flight has proved less straightforward. Among the admittedly impressive flights were some spectacular and worrying crashes. As any foiling dinghy cat crew will confirm, scorching around at double-figure speeds is great until it goes wrong.

Safely on the boil

So keeping the machines safely on the boil has been one of the biggest issues. The problem is class rules can often prevent designers from using forms of automatic feedback such as those used on the Moth in which ride height is fed back mechanically to adjust a flap on the trailing edge of the T-foil on the daggerboard automatically.

America’s Cup rules do not allow such systems. Instead the foils, which are a part of the lifting daggerboard system, can only be adjusted by raking the daggerboard fore and aft to change the angle of attack of the lifting part of the foil.

The Cup boats that will be launched for 2017 – along with their current development boats – are allowed to cant the boards inboard from the vertical as well, which helps to control the ride height. “If the rules were taken away we would eventually be able to create a better boat,” says Kramers. “There is nothing new in the physics book, it’s how you control the various systems that’s the key.”

In the previous Cup the rules strictly prohibited changing the angle of attack of the T-foil rudders during the race. Teams had to decide what setting they wanted for the conditions and then lock the angle of attack. In simple terms this was akin to setting the trim of an aeroplane for pitch before take off and then not adjusting again for the whole flight in the hope that conditions would stay the same.

Such strict rules led to some nerve-racking moments for crews when conditions changed during the race.

Since then the rules have been relaxed and teams can not only adjust the rake of the T-foil on the rudder while racing, but its rake can be related to the angle of the main daggerboard foil – or ‘mapped’ to it, as the techies like to say.

This is one of the key changes that have allowed the new generation to foil more steadily and, many hope, more safely. This is good news for the rest of us as this is exactly the kind of technology that will be required for mainstream foiling if it is ever to filter downstream.

Keeping a balance

But the improvements have gone further. Canting the J section daggerboards inboard allows the lower section of the daggerboard and the tip on the other side of the J to act like a V section foil, which helps the boat to find its own ride height as the immersion of the V varies with the speed of the boat.

More daggerboard cant means better automatic ride height control, but this reduces the amount of sideways force the foils can exert and hence risks the cat slipping sideways if it has risen too high with too little foil in the water.

So a fine balance is required when adjusting the highly loaded boards and to achieve this means using hydraulics rather than ropes, blocks and cleats. Yet on some occasions it is the number of operations as well as the fine control, that require a more sophisticated control system.

“During a tack or a gybe all four foils [two daggerboards and two rudders] will be adjusted. That’s a lot to ask of a five-man crew, but also a lot of hydraulic oil that needs to be pumped around the circuit,” says Grant Simmer, Oracle Team USA’s chief operation officer. “A crew’s output is about 400W each and in a crew of six we’re using all of that most of the time to drive these boats.”

Seeing the physical demands on the crew and their work rate, which is higher and more sustained than in any previous Cup, drives home just how much power would be required to drive a foiling racer-cruiser of the future.

Looking to the skies

But the development of control systems doesn’t stop with simply moving the foils. The new sophisticated systems also affect the design of the foils themselves. “Without the new control systems we would have to design more conservative and forgiving foils, which are slower,” declares Kramers.

Just as modern fighter jets are more manoeuvrable because they have fly-by-wire systems that operate beyond anything that could be achieved by manual human input, so Cup boats are faster because of control systems.

Little surprise then that the big guns have turned to experts in other fields to help them in this area. Land Rover BAR has worked closely with motorsport and appointed its CEO from McLaren, while Oracle Team USA has hooked up with Airbus.

Les Voiles de Saint Barths 2015, © Jesus renedo

Gunboat’s foiling G4 cat, which suffered an embarrassing capsize during early trials, is having a new, sophisticated control system installed to allow the boat to be sailed comfortably by just one or two crew.

“The new system will control the main foil and the rudder foils as well as some of the sail controls,” explains Ward Proctor of Marine and Hydraulics, a Helsinki-based company specialising in advanced control systems. “The system will control the fore and aft rake of the foils to keep the boat flying level. The helmsman will have the rudder control within the tiller, but if the boat starts to get outside certain parameters, such as heel or pitch, then the system will automatically lower the boat back down into the water.”

Marine and Hydraulics has a track record of producing sophisticated solutions for a variety of craft, from PLC packages for luxury performance cruisers, to a gimballed saloon aboard a Shipman 63.

Proctor expects the G4 system to be up and running by spring and believes that there could be more to come. “We’ve already had enquiries for a 100ft foiling cat,” he reveals.

Motion damping for cruising

So while the Cup and other prestige racing designs are providing the focus for modern systems, it is projects that don’t have the constraints of class rules that are starting to take the application of new technology forward. All of which makes it easier to see how control systems might benefit more mainstream craft.

Land Rover BAR in Portsmouth

“Modern electronics and solid state gyros are now readily available and so cheap that electronic control devices could easily be incorporated,” says Andy Claughton, Land Rover BAR’s chief technology officer. “The automatic electronic stabilisers in quadcopters that you can buy in any high street are an example of that.”

Given the ability to sense motion more accurately than ever before, combined with a wealth of electronic processing power and efficient electric motors, the idea of low-drag motion dampers for cruising yachts, similar to those used in powered craft, is becoming more likely.

And perhaps the idea might go even further to allow power to be harvested when the devices were not being actively used. For example, a company called Zehus is producing intelligent hubs for electric bicycles that mean you can charge the internal battery while cycling. When the load on the pedals reaches a critical limit, the electric motor starts automatically to provide assistance.

This small, self-contained unit, which can be controlled via Bluetooth by your smartphone, is already available and being used by some bicycle manufacturers such as Klaxon.

So, when you start to imagine what such systems could do for sailing, automatic motion dampers for cruising yachts are surely only a small step away.

But if motion damping isn’t a prime concern, how about trebling the potential performance of your boat under power by simply fitting a retractable T-foil at the stern?

As we reported in 2013, Andy Claughton’s SpeedSail system offers a means of modifying a boat’s wake to prevent her squatting down at speed under engine while at the same time helping to dampen pitching motion simply by adding a horizontal underwater foil at the stern. Claughton has tested the system at full size and the results are impressive.

Foiling in the future?

So as the world’s most advanced foiling catamarans take huge leaps forward in performance, scorching around in front of thousands of spectators, it is tempting to ask whether we may all be flying in the future. Yet the answer is likely to be no, at least not for family cruising.

And then there’s the cost. Supporting any kind of boat on a horizontal section the size of a tea tray is an expensive business. Cup boat foils cost an eye-watering US$1m a pair, or $500,000 each if you thought the first number was a typing error.

If we’re talking a new generation of section shapes there is little that is going to change for the rest of us. “The book on hydrofoil sections was written 50 years ago. Nothing has changed since then,” says Claughton.

Instead, the real benefit will come with reliable and affordable control systems that will allow us to boost performance for those who want it, while improving the behaviour and motion of our cruisers. Increasing righting moment without increasing displacement using devices such as DSS, along with developments in modern control systems for foils, looks most likely to offer the greatest benefit in the long term for most us.

The genie is out of the bottle. After all, who would now want a car without power steering or ABS?

FAQs

How fast are we talking?

The 45ft America’s Cup development boats based on AC45 hulls – often referred to as ‘T2’ – are hitting 30 knots upwind and 40 knots downwind.

The top speed so far for the smaller GC32 cats that will be used in the Extreme Sailing Series is 39.21 knots achieved by Alinghi on Lake Geneva while the top dogs aboard the diminutive International Moths are now clocking 36 knots.

How much faster can they go?

Cup teams shy away from talking about specific numbers and, while 50 knots downwind seems possible, many point to the ability to tack and gybe reliably on foils as being the bigger benefit.

Is foiling dangerous?

Opinion is divided here. There is additional risk. Falling off the boat at 40 knots onto water is much like falling out of a car. At these speeds the water feels solid. Being hit by foils is a serious risk, which has already resulted in serious injury.

On the other hand, there are top sailors who say that they are far more comfortable bearing away through the danger zone on foils than they are on a conventional multihull where the leeward bow has a tendency to bury.

Also, once at speed, foiling cats are usually very stable. Turning corners or sailing in big waves can be a different experience though.

Will cruising boats be foiling soon?

For monohulls, foiling in the future is very unlikely. Achieving the kind of power to weight ratio required to fly is very difficult as some of the world’s top, stripped-out race boats are discovering.

Multihulls may be a different proposition as they are better at generating high righting moments without putting on too much weight. But foiling in future will also rely on incorporating either self-balancing foils or automated systems that ensure safe and steady flight. The technology may be there, but at present we’re still along way off a usable solution for mainstream sailors.

How might foil technology affect me?

The Dynamic Stability System (DSS) is a good example of how the smart use of foils can create more righting moment, allowing a stiffer boat that sails more upright with a better motion.

So too are systems like the SpeedSail foil that dramatically improves performance under engine.

Will we go faster?

Generating more righting moment with a system like DSS means more power to start with, but might also mean the weight of the keel can be reduced and lead to a possible reduction in displacement further helping a potential hike in performance.

Could a foil improve cruising comfort?

With the DSS system or perhaps roll stabilisers similar to those used in motor cruisers and ferries, combining efficient, slender foils with modern motion-sensing electronics and powerful small electric motors could see stabilisation make its way onto sailing boats of the future.

The Dynamic Stability System (DSS) also generates more righting moment when the boat is under way. It has been around for over a decade and has been incorporated into a number of designs. The system’s founders believe that the retractable board has benefits for cruising boats as well as racers.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.