Invariably, when a yacht approaches a marina berth with a couple on board it will be the man at the helm and the woman holding the lines. Why is that? asks Elaine Bunting

In 1950s movies, when a man and woman were going somewhere together, it was invariably the man who drove the car. Driving was a male role, like carving the Sunday roast or deciding how to vote. Even among my parents’ generation, the next along, I knew of a woman who was not allowed to drive her husband’s car, as if operating it safely were somehow beyond her mortal powers.

Today such notions seem preposterous – at least in Western countries. Yet some aspects of sailing still resemble a 1950s Technicolor world. Go to any harbour or marina in the world and see which one of a couple is at the helm as a yacht approaches.

In 90 per cent of cases, or more, it will be the man at the wheel and the woman doing the heavy work of grappling with lines and fenders, jumping onto the dock and tying up.

Surely this is the wrong way round? In a logical world, it would make sense for the woman to be at the wheel and the man doing the lifting, throwing, jumping and pulling. So why aren’t women at the helm?

And why aren’t more men concerned that their partners might not have the skills necessary to return and pick them up if they fall overboard? Or to navigate and sail their yacht safely back to shore if necessary?

Women scarce in professional sailing

Top professionals such as Ellen MacArthur, Dee Caffari and Sam Davies have highlighted women’s sailing abilities, but actually women are much scarcer in the professional world than they are in amateur racing and cruising. Women make up a large proportion of the Ocean Cruising Club, for example, about 40 per cent of racers at Cowes Week and around a fifth of sailors on the ARC rally. Yet often the roles on board are divided into ‘blue and pink’ tasks.

This is at odds with life on land and is a subject seldom discussed. It can be construed as provocative, sexist even, and anyone who raises the debate on forums is liable to go down in flames.

But things are beginning to change. The subject of women in command is being spoken of more openly. It is the subject of an upcoming symposium being run by the Irish Cruising Club. The Cruising Club of America runs a course titled ‘Suddenly Alone’ at which couples interested in coastal cruising are invited to consider what skills each of them has to sail safely.

The fact is that if you sail two-up offshore you are, in effect, two single-handers in need of duplicate skills.

If you’re reading this as a castigation of men not giving over the helm to their partners, though, you’d be wrong. The reason so many women don’t take charge of manoeuvring, navigating and other key tasks is because they are afraid to, they don’t have the confidence. That lack of confidence can make women reluctant sailors, which means that frequently the guy’s dreams of sailing away into the sunset stay just that – dreams.

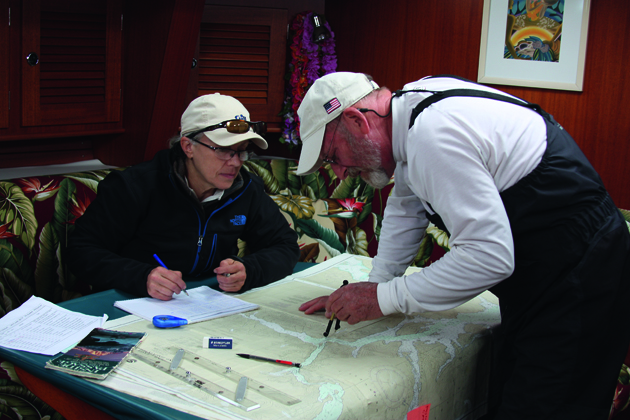

John Neal and Amanda Swan Neal sail round the world on their Hallberg-Rassy 46, Mahina Tiare III, and run expedition courses for sailors (www.mahina.com). When I asked them ‘why can’t women drive?’ they replied: “This is a question that we ask ourselves constantly as a fair number of our expedition members would do anything to get their partners interested in sailing and cruising, much less interested in driving.”

To their minds, it comes down to the different way men and women learn. Their experience is that men are happier to learn intuitively whereas women prefer to be sure they can do something before they take it on. “In a nutshell, it’s about gaining the confidence, which requires practice, a good support system, grounding knowledge and experience.”

Instruction and practice

“It’s difficult to place a finger on the reluctance of women to step into a task when in many situations men appear to take control quickly and effortlessly, but whatever it is, in order to take responsibility, all sailors need time, learning goals, instruction, involvement and practice,” says Amanda. “Dealing with emotions and finding the courage to overcome fears will enable you to move forward as long as you have a trusty crew and realise there will be mistakes.”

John adds: “During expeditions, we have a captain of the day and a docking/anchoring master. Guys tend to be more intuitive when it comes to docking, and women tend to need to talk it through more than once before approaching the dock. When we have couples aboard, we frequently end up sending the guy to the bow to handle the bowline so that his partner can dock without any instruction from him.”

Rachael Sprot is a professional charter skipper also leading expeditions and adventure sailing voyages (www.rubicon3.co.uk). She says: “I can comment from the opposite perspective. I grew up sailing with my parents, and my mother was the sailor and father took it up for her. He never parks the boat or does the maintenance on board, she does it all!

“The fact that short-handed sailing can be stressful makes couples revert to their default settings: if it’s windy or you’re in a rush, the more experienced person goes on the helm. Add to that the fact that your partner probably isn’t the best person to teach you how to park and it means that, even when the conditions are right, you’re not in a good learning environment because you don’t have the right instructor.

“From a non-couples perspective, women tend to be more cautious about taking on the responsibilities of boat handling in high-pressure environments. I think generally women prefer not to take quite as many risks, and are more afraid to fail than their male counterparts.”

Sprot suggests: “Couples should learn separately and make the effort to let the less experienced person take the helm and build experience. Increasingly, the opportunities are there to take leadership roles if you want them, you just have to be prepared for the fact that you will make mistakes along the way.”

She adds: “I’d like to see women crashing into pontoons and shrugging it off, as well as parking.”

[Sprot is a fine role model for women taking the lead. See her feature on cruising in the ice HERE]

Sharing the driving

Speaking for myself, I enjoy driving, whether it be under sail or bringing a yacht alongside under power. I rather like the tricky bits. But my husband likes them just as much, so we’ve always shared it out.

Have I ever got it wrong? Certainly, and so has he. So has everyone. But practice is the best way to learn.

Daria Blackwell learned to sail before she met her husband, Alex. Now they sail together. ‘I’ll let you in on a little secret,’ she writes. ‘If I had known how much easier it is to be at the helm than in any other job on the boat I would have taken it up decades sooner.’

I think she hits the nail squarely on the head when she comments: ‘I realised that the reason many people have problems is that they come in unprepared. They don’t have their lines set, they are still fumbling with fenders, they come in too fast, and they don’t observe the natural forces – wind and currents. If you come in prepared, your chances of getting it right are pretty high unless nature takes its toll in conditions you couldn’t have predicted. Then, anyone would have difficulty. But that’s not the usual situation.

‘Ask yourself, what’s the worst that can happen? You’ll miss the mooring and have to try again. Just don’t foul the prop on the mooring line and you’ll be fine. Work your way up. Try docking in calm conditions, in slack water, going very slowly to learn how your boat behaves. Go a little faster if you lose steerage, slower if you’re uncomfortable. Don’t let anyone intimidate you.’

Sailhandling, navigating and essential maintenance are also part of the skill set women sailors should have, and not be deterred from acquiring. A couple sailing on their own are co-skippers and ought to have a fair share of seamanship skills.

Co-skippers and seamanship skills

Andrew Bishop, managing director of the ARC, is an experienced double-handed sailor himself, and has led forums for short-handed sailors for 11 years. He has heard many couples’ fears.

“We make the point that it’s important that both parties share responsibilities and knowledge so that each can do the other’s jobs to a greater extent. I don’t think people prepare for this enough,” he says.

“I always ask how many male skippers let their wife drive the boat into marina berth. It’s usually very few. A very small number say they both helm on a regular basis. I emphasise the importance of doing that, but it doesn’t necessarily change as a result.”

When I ask how he thinks two-handed couples could prepare better, Bishop replies: “Thoroughly thinking through their sail handling and how to deal with that, and definitely sharing the ability to handle the boat in a situation where one is left on their own, be it a man overboard or berthing the yacht because the other is incapacitated.”

“When Alex and I decided to cross oceans, we also agreed that we both had to learn some of everything the other did,” says Daria Blackwell. “I took a diesel mechanics course and he did a medical/first aid course. I wanted to survive if we had an accident.”

And she remarks that their different approaches to learning can be very useful. “With the diesel mechanics class, I learned the most important thing is the service manual. A guy would never look in it. If Alex can’t figure it out, I read the manual. It’s worked on many occasions. We just think differently. That helps.”

Overlapping knowledge also allows couples to decide on specialist areas. “Amanda is responsible for sails, rigging and fixing things other than the engine and heads,” says John Neal, “and I am responsible for navigation, weather and communications.

“We share sail changes, troubleshooting, choosing overall destinations and anchorages, provisioning (except I take care of breakfast and everything related) and varnishing. We switch at the helm when anchoring, but for some reason Amanda prefers if I drive when [coming alongside].”

So if women can drive just as well as men, and ought to know how to so that they can take command when it’s needed, why don’t more wives and partners do it? Is it like voting, or driving cars: we just need to be given an equal opportunity?