Of all sailing manoeuvres a heavy weather gybe is the one that can strike fear into the hearts of even professional racers. Jonty Sherwill asks Rob Greenhalgh for tips on how to deal with it

With your heart rate rising like a jockey heading towards Becher’s Brook in the Grand National, your gaze is fixed on the gybe mark that’s getting ever closer. You may have been through this procedure countless times before, but picking the right wave at the right moment to gybe is a fresh challenge every time.

At play are elemental forces poised to have their fun if you drop your guard at a crucial moment. Today is more testing than usual, a gusty 25-30-knot wind is pushing against two knots of ebb tide and kicking up a short, confused sea, plus a boat overlapped to windward is looking keen to gybe as soon as you do.

“Everyone ready?” calls the helmsman as the boat comes abeam of the port hand passing mark just before steering into the gybe. With fear now suppressed by adrenalin, the spinnaker trimmer has eased the sheet forward while the mainsheet trimmer is hauling in metres of mainsheet and the mast man pumps the sheet at the mast.

It all looks to be going so well, but just as the ‘trip’ is called the boat has heeled wildly to windward and is bearing away even more sharply. As the helmsman fights to keep the hull under the rig the mainsail flies across, pressing the boat further into a crash and any chance of recovery has gone.

Now with the boat on its side and the spinnaker spread out to leeward the only upside is that you’ve narrowly missed hitting the turning mark on your way back uptide. Meanwhile, the boat overlapped outside is romping off down the next broad reach.

How come they got it so right and you so badly wrong? We ask an expert.

1. Speed is your friend

In a windy weather gybe your priorities change. Focus must be on survival, not an elegant roll gybe, but making sure the gybe is completed safely and without a wipeout. A good gybe is one where the boat is on course and the spinnaker is in one piece.

The faster you go in, the less the apparent wind speed felt by the boat, so pick a wave to accelerate if you can – think about having someone looking aft calling the bigger waves as they arrive.

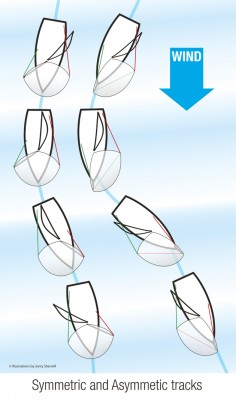

Sailing slightly higher prior to the gybe will help to build some speed. It will also keep the boat more stable and allow a larger turning angle, which will also help to create some momentum for the boom, and hopefully avoid a large steering correction after the gybe.

Often the vang needs to be brought on for the gybe as this will make the boat more stable before and after, and also make it easier to sheet the main on.

2. Getting the boom over

Getting the boom over safely is the key – in higher winds it’s more about the mainsail and less about the spinnaker.

Sheet on the mainsheet prior to the gybe (about halfway) and then get your strongest crew ready on the ‘A’s at the mast to go big on the mainsheet and get it to the centre, but don’t ease the mainsheet too quickly otherwise the boat may lose control.

Timing the mainsail with the steering is vital – the loads on the main will be too big to move until the boat is turning through the gybe, but if the mainsheet gets centred too late then the helmsman will have to over-steer to get the boom across, which could result in a broach out of the gybe.

Tripping the spinnaker pole should be as normal – quite late once the boom is crossing the centreline. Windy weather downwind trim for the spinnaker should be a little tighter all round, keeping the spinnaker closer to the boat so it does not roll so much, with both tweakers down hard to keep the leech and luff as tight as possible.

3. Keep talking to the driver

Good communication with the helmsman is vital. Keeping weight aft for as long as possible is recommended, only taking a few crew forward to do their duties as required.

It’s very important to have any large gusts or waves called. You are probably looking for a light spot to gybe, but also hopefully combined with a large wave.

The helmsman or tactician needs to take control of the comms. “Standby gybe” (sheet on main to 1/2 etc) = build speed and wait for good moment. “Bearing away” (helmsman initiates turn) = centre main, trip pole, etc. The helmsman should try to let the crew know how much control there is! Calls of “Pole made”, etc, will tell him that the crew are ready to build speed.

4. Respect the conditions

Heavy weather gybes are seldom practised so you just learn on the job. Some windy races will have been won by skippers who decided to drop the spinnaker rather than risk the potential damage of a big broach.

Wind against tide will always increase the true wind and it will make the sea state worse, so you need to factor that in. Very often laylines can be missed by a long way while waiting for a light patch to gybe in.

Always remain aware of the course and tactical requirements, and if you are flying past the layline then get the spinnaker down and tack around. Remember without a spinnaker gybing can be more dangerous.

It is also worth considering that you may not want to gybe, but are happy to hoist the spinnaker, in which case I would ascertain which is the longest gybe downwind and hoist the spinnaker. Then you can drop for the gybe/tack. The jib can be left up, especially if gybing is not an option.

5. The A-sail gybe

For an A-sail gybe the big difference will be boat speed. If it’s a modern planing boat the gybe should be relatively easy. The focus still needs to be on making sure the boom will cross, but once the boom is over and you’re in control the spinnaker can be set quickly.

For a non-planing boat, it will require more effort, sheeting on the main halfway prior to the gybe. The helmsman will need to steer enough to help initiate the momentum of the boom and then reduce the turn once the boom is over – very similar to a symmetric sail, except that the angle prior to the gybe may be higher and hence a larger turn may be required.

If the A-sail is on a pole then it’s probably best to clear the pole well before the gybe, get back up to speed and then take on the gybe before repositioning the pole.

Rob Greenhalgh won the first of his three Volvo Ocean Race campaigns in 2005/06 aboard ABN AMRO One, but made his name in dinghies, including World Championships in the International 14ft and 18ft skiff classes. A full-time offshore professional sailor, Greenhalgh says his first love is dinghy sailing, which currently includes a new challenge, the foiling International Moth.