Springtime can throw up some volatile and changeable weather, quite unlike summer. Matthew Sheahan and meteorologist Chris Tibbs offer five key tips to help you prepare for those early-season races

The boat is sorted, the sails back on board and the crew lists are taking shape, but how much thought have you put into early season spring weather?

Why should you? You’re racing on a patch you know well and can probably recite the local tactical wisdom verbatim. This knowledge worked well last season, so why should the spring be any different?

As the spring coughs and splutters into action, squalls, sudden downpours and rapid changes in wind strength and direction can create schizophrenic weather that changes abruptly and in which many normal rules don’t apply. By summer conditions should have settled into a more familiar pattern.

Among the seasonal influences, temperature fluctuations from week to week and differences between land and sea temperatures can be large at this time of year and create springtime oddities.

In the UK during April and May there are often more northerly breezes than at other times of the year when south-westerlies prevail. For the UK and Europe, a northerly air flow can mean air temperatures plummet rapidly as dry polar air is drawn down over the land. This air is readily heated, causing the development of cumulus clouds that can quickly create significant local conditions.

Separating the snakes from the ladders that these conditions create can play a large part in determining your fortunes on the racecourse.

The tracks of weather systems can also be different from those during the bulk of the season as influences such as the Azores High, which deflects many depressions to the north of the UK in the summer, is still starting to develop. Like the absence of a firewall, the lack of the high pressure zone means the UK is more exposed to fast-moving low-pressure systems that sweep across the country.

So here are five tips on weather for the early season series plus one special bonus tip: don’t forget that at some point in the spring, the clocks go forward. There’s nothing quite as slow as turning up to the start an hour late!

1. Squalls

A northerly airflow in clear, crisp conditions when the land can heat rapidly creates the perfect climate for the rapid development of squalls and showers.

Classic April showers develop as the dry polar air heats up briskly and rises. With no stabilising upper layers of air above, the heated air shoots up and condenses, forming a towering cumulus cloud before pushing on through the freezing layer to form ice crystals.

This creates the distinctive flat-topped cumulonimbus cloud. Eventually what goes up must come down, but rapidly as a shower forces a rush of air beneath it.

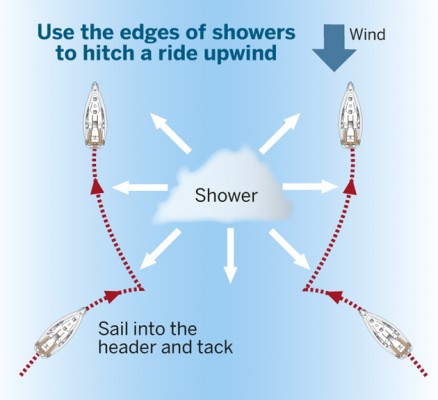

If it’s raining and you’re sailing upwind, head for the edge of the cloud, get headed on the way in, tack and get lifted as you pass the cloud.

If it’s not raining, avoid the cloud as the opposite will be occurring as air is sucked up.

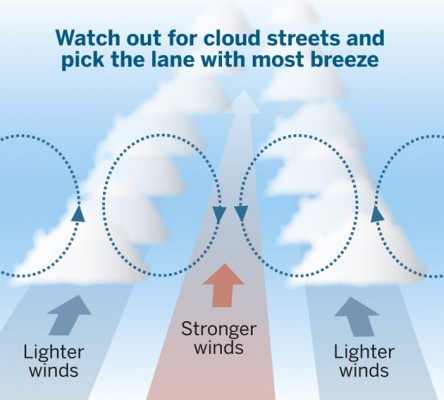

Northerly conditions often produce cloud streets on land where the cumulus clouds align in line with the wind. This can cause bands of lighter and stronger wind to extend out over the water. Generally winds will be lighter under the lines of cloud and stronger midway between them. Pick your lane carefully to sail in stronger breeze.

Streets can also exist in clear conditions. While they are difficult to spot, be aware of the possibility of bands of pressure and try to feel where they are.

2. Strange shifts off the land

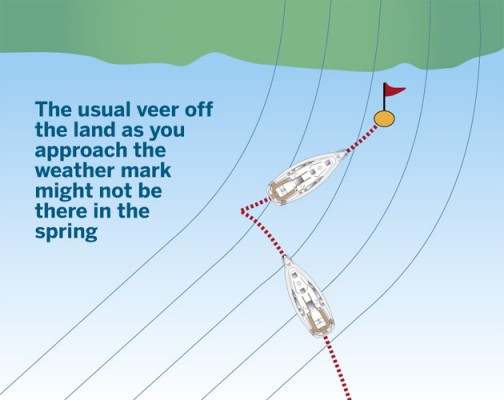

An offshore breeze usually veers as it leaves the shoreline, but if the water is cold, as it is in springtime, there is greater stability in the air closer to the water surface, which may reduce or prevent the change in direction. So the shift you were planning for as you headed in towards the top mark might not be there.

In fact, sometimes, when the air is very stable, the breeze can be backed rather than veered for a short distance close to the shore. This is often accompanied by poor visibility as warm air flows over cold ground and onto a cold sea, causing mist or fog.

3. Lack of sea breezes

Mid-season, early wisps of cumulus clouds and a light offshore breeze will be the first indications of a sea breeze later on. But in the spring the development of a sea breeze is less likely, as the land is unlikely to heat up sufficiently, for long enough and over a large enough area to draw the breeze in.

More likely is a boosting of the gradient breeze with the potential for showers and squalls to develop.

Although spring days can feel like summer once the sun’s up, the land can still cool further and more quickly overnight. The risk is that the breeze starts off feeling lighter than normal in the morning, but then builds more than expected later on – just when you realise that you’ve left the heavy weather sails in the locker ashore.

4. Fog

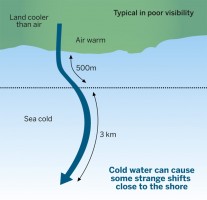

When warm moist air blows over relatively cold water fog can form as the moisture is cooled to below its dewpoint. In winter and spring the water inshore is usually colder than it is offshore in deeper water and so fog forms more frequently along the coast.

Apart from the visibility issues, there is often a stronger wind gradient and wind sheer in foggy conditions as the lower, colder layers of air are more sluggish and less inclined to rise.

This lower layer runs more slowly than the wind speed higher up, making the wind gradient more pronounced than normal.

The effect also causes wind sheer, which can be in the order of 20°, which means that you may want to sail with more twist in your sails on starboard and less on port.

5. Temperature and the early reef

Cold air often feels like heavy air and yet there is little evidence to suggest this is the case. The change in density between cold and warm air is insufficient to produce large variations in what is often described as ‘the weight of the wind’.

The reason is more likely to be the result of the mixing of lower layers of air and the wind gradient (see Tip 4).

But whatever the technicalities, the practical aspect of racing in colder conditions is that it will often be necessary to reef earlier than you would expect. Anticipate changes in wind speed and err on the conservative side, changing down earlier than you would normally if you think the breeze is about to increase.

Some racers even adjust the wind speed on boat speed targets slightly specifically for the spring.

Chris Tibbs is a meteorologist and weather router, as well as a professional sailor and navigator, forecasting for Olympic teams and the ARC rally. He is currently on his own circumnavigation with his wife, Helen. His series of Weather Briefings can be seen here

See also:

Chris Tibbs prepares his own boat for an Atlantic crossing

The best route for an Atlantic crossing

Taking the northerly route across the Atlantic

Offshore weather planning: options for receiving weather data at sea