Toby Hodges jumped at the chance to helm the J Class Endeavour, one of the world’s most distinguished and beautiful yachts.

The mighty press of canvas fills as her bows fall off from head to wind. As she loads up and heels, everything changes – there’s a distinct mood adjustment aboard. It’s a switch to a more serious attitude from the sailors perhaps and their respect both for the craft and the loads she creates.

It seems there’s a change in the yacht herself though. Now silent, slipping through the water Endeavour seems totally in her element.

Skipper Luke Bines relays to the trimmers “coming up ten”. Endeavour’s tumblehome is fully immersed, water streams over the capping rails now, as she loads up and points her bow to weather. And that’s when the magic really starts.

Trimmers aboard Endeavour with Toby Hodges at the wheel.

What a day. Not many people get to take the wheel of a J Class, so to be handed the helm for four hours of sailing in ideal conditions still makes me feel giddy thinking about it.

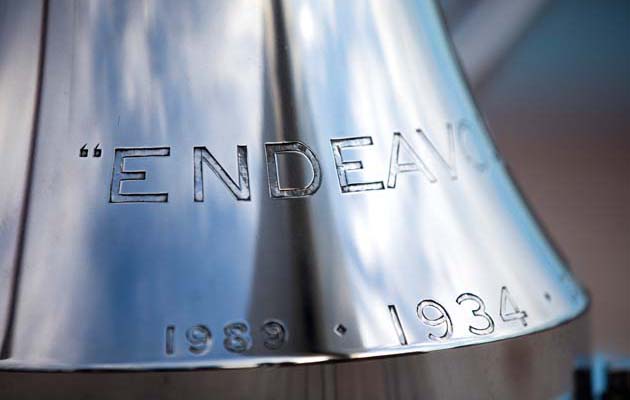

Endeavour is not only described as the most beautiful J Class, but the 1934 America’s Cup challenger is perhaps more highly regarded than any other single yacht in the world.

She is currently up for sale and her brokers Edmiston created a unique opportunity for us to sail and photograph her from her home port of Cascais in November.

Sailing a legend

Departing the marina berth that morning was a smooth, near silent operation. Once at sea the mechanics kick in as the process of setting sail begins.

The 490sq m mainsail with its distinctive JK4 insignia is hoisted. “On the lock,” the crew finally shouts back to Bines. “Cunningham on, lazys off,” he replies.

Endeavour with twin headsails.

A mastbase winch ferociously spits out halyard tails as the foresails shoot up in the blink of an eye and I am instantly reminded of how modern technology has transformed the way a yacht designed over 80 years ago is handled.

That said, even in her 1934 launch year Endeavour was ahead of her time. Sir Thomas Sopwith and his lead engineer, Frank Murdoch, applied their aircraft design experience to the rig and deck gear of Endeavour and helped introduce a number of innovations.

These included winches that could be rowed using horizontal bars, strain gauges on rigging wire and a masthead wind vane with a windspeed repeater.

In 1934 Endeavour had a ketch mast temporarily stepped and was sailed and towed across the Atlantic where she began Britain’s closest challenge ever to lifting the America’s Cup.

Eighty-three years later, however, she is for sale lying in Palma – a turnkey original J on the eve of the biggest year ever for this class.

The 10-15 knots of wind that morning was the ideal strength for Endeavour and her 3DL cruising sails. Although Js race with genoas now, the more manageable yankee and staysail are set when cruising.

Included in Endeavour’s sale is a brand new full set of 3Di racing sails (three hours’ use) plus spinnakers.

On taking the wheel I couldn’t help but think of who has sailed the boat over two lifetimes. Sopwith won the first two Cup matches against Vanderbilt’s Rainbow during that 1934 challenge and four out of six starts.

He certainly had the boat to win the Cup – Endeavour’s universal appeal was sealed that year – but he was let down by a late crew change and tactical errors. And in 2012 I had the privilege of witnessing Torben Grael take this wheel and helm her to victory in St Barth when four Js raced for the first time.

I am brought back to the present by the wholly unnatural mechanical sound of winches labouring under load. The ease of a sheet vibrating through the deck, or the shudder as the mainsheet jerkily comes on, are the harsh reminders of the loads exerted aboard today’s J.

There’s a big load on that wheel too when we harden up, yet Endeavour responds handsomely to the trim of her sails. I remain in a trance, looking along 100ft of clean decks to that pin sharp bow.

An offshore breeze blows a decent, but relatively smooth ground swell. As Endeavour heels the incredible power and load of her keel-hung rudder is felt. Trying to turn that immense appendage through a tack at speed is a workout in itself, but as I hand-over-hand the spokes rhythmically, her bow starts to respond.

I quickly appreciate how necessary it is to have the mainsheet trimmer directly in front of the wheel – without coordinating with him, turning the wheel would have little effect.

A push button panel also provides the trimmer with the suite of hydraulic controls – indeed during the St Barth’s Bucket in 2012, it was designer Gerry Dijkstra who operated the traveller, cunningham, outhaul and backstay from this remote panel.

The Cariboni hydraulic rams that drive the mainsheet traveller lie hidden in lockers beneath the aft deck. These rams are a perfect example of how the deck layout has improved, saving the need for two crew and two winches when racing.

The deck of JK4 today is clean with the number of winches reduced to the minimum. Gone are the large dorades in favour of forced aircon. “She looks more like the 1934 Endeavour now than she did in the 1980s,” Bines remarked.

The inviting cherry woodwork within Endeavour’s dining area and saloon – the latter with a working open fireplace.

The sun breaks through and the breeze rises with it, up to 17 knots now. The upwind figures of 9.5 to 10.5 knots and up to 12 knots reaching are typical for a J. But it’s the consistency with which she maintains such speed that delights. Displacement and length work perfectly to ensure Endeavour just keeps slicing through the water.

A rediscovered jewel

Endeavour’s history is one that typifies the highs and lows of the J Class fleet. She was sold for scrap in 1947 only to be bought hours before demolition.

When American Elizabeth Meyer purchased her in 1984, after three decades laid up in Solent mudberths, Endeavour’s resurgence, and that of the J Class, slowly began.

Meyer had Endeavour reconfigured by Dykstra & Partners, shipped to Royal Huisman and restored in the late 1980s, before cruising and racing her all around the world.

Nav station aboard Endeavour.

Twenty years later Endeavour’s current owner commissioned a subsequent major overhaul at Yachting Developments in New Zealand. Virtually all machinery was replaced or upgraded and a new Southern Spars carbon mast stepped with ECSix rigging.

John Munford and Adam Lay reconfigured her crew accommodation, while subtly keeping an ‘original’ 1980s look to the interior.

The saloon is, as it should be, the wonderfully welcoming heart of the boat. One can imagine the lively dinner parties held around the dining table.

Guests would then move to the green leather sofa, place their liqueur on a coffee table supported by Endeavour’s old compass binnacle, and enjoy the warmth of the working open fireplace.

Endeavour remains seaworthy in her design below. A sail locker still resides beneath the saloon sole, low and central, where it would have been originally.

In the passageway that leads to the owner’s aft cabin, is a fabulous navstation, with a U-shape leather seat that allows you to sit to a chart table facing forward or aft. The owner’s cabin features an offset berth and leecloths.

Owner’s cabin aboard J Class yacht Endeavour.

Jon Barrett was integral to both Endeavour’s major refits. He was project manager at Huisman and the owner’s rep when she went to Yachting Developments. He knew where to source every fitting – down to where to get the stars on the light switches recast.

I asked Barrett what makes Endeavour so special. “She has a unique history. During the closest match in history, she was eventually out-sailed, but her reputation as a beautiful and fast J was well established.”

She is also resilient, he says, describing her decades of disrepair. “In the last 25 years, in addition to the normal cruising routes, she has sailed to China and Japan, to New Zealand and the fjords of Norway and Alaska. I would guess that she has trekked the globe more than most yachts and certainly more than all the current Js.”

I could not think of a more prestigious vessel to purchase – to be a guardian of – particularly in this, what could be the most historic year yet for the J Class.

Enormous primary winches aboard Endeavour.