Meet the little yacht with a huge heart and history, a famous survivor of the 1979 Fastnet Race. Nic Compton sails on Assent

It’s a gloomy, grey afternoon on the Solent and I’m in a camera boat taking pictures of a yacht sailing off Lymington. There’s a light breeze blowing and a moody, late afternoon glow in the sky but, to be honest, it’s not exactly blowing my socks off.

Then, the skipper starts gesticulating, making big belly signs. I don’t understand what he means – is he hungry or feeling pregnant? A few minutes later all is revealed as the crew break out a spinnaker that inflates into blue and white stripes. At the same time, the breeze picks up, and the yacht starts shooting across the jade green sea.

Suddenly, this looks like the yacht she is: one that could confound all expectations and win a major race; a little boat that could survive a serious pasting and give the big boys something to think about.

With spinnaker up and a decent breeze, Assent looks like a winner again. Photo: Nic Compton

For this is Assent, the Contessa 32 built by Jeremy Rogers in 1972 and the only boat in her class to finish the 1979 Fastnet Race, in the face of a storm which wiped out most of the fleet and killed 15 competitors.

No discussion of that tragedy is complete without reference to the small but hugely significant part this boat played.

On board for the photoshoot are the children and grandchildren of Jeremy Rogers: brothers Kit and Simon and their respective eldest children, Jonah and Hattie.

Happy families: Simon (left) and Kit Rogers (right) with eldest children Hattie and Jonah. Photo: Nic Compton

They know these waters like the back of their hands and are intuitive sailors. There’s no shouting, no panic. Their approach is cheerful and understated but there’s no doubt they know absolutely what they are doing.

Despite the banter, there’s a serious agenda here. Kit has decided to mark the 40th anniversary of that deadly Fastnet by entering Assent in this year’s race.

“The 1979 Fastnet is not something you want to celebrate,” says Kit. “It was a terrible disaster. The fact that Assent did so well and made a name for herself had nothing to do with us.

“I was 11 at the time, staying in a hotel in Plymouth with my mother and brother, waiting for my father to come back. But entering Assent in the race this year seems like a good way of commemorating that tragedy and honouring the people who died in the race.”

Article continues below…

Fastnet Race 1979: Life and death decision – Matthew Sheahan’s story

At 0830 Tuesday 14 August 1979, aged 17, five minutes changed my life. Five minutes that, despite the stress of…

Fastnet Race 1979: Why was the storm so devastating?

There was nothing in the forecast at the start of the 1979 Fastnet Race to indicate a storm, but a…

As part of their qualifiers for the 2019 Fastnet Race, two weeks earlier Kit and Simon had taken part in the De Guingand Bowl Race, racing 120 miles up to Portsmouth, around the Isle of Wight to Weymouth and back.

The last leg was particularly gruelling: a 50-mile upwind beat against winds gusting up to 40 knots, with seas to match. But Assent took it all in her stride, at one point taking overall lead against some much bigger IRC boats – though her crew fared less well.

“It’s a funny thing about boats,” says Kit. “Assent is just a Contessa 32. There are 650 of them out there which all came out of the same mould and are pretty much identical. Yet there’s something special about her.

“It’s probably me projecting a bit, but somehow she feels different, because I’ve got this narrative running, because I know where she’s been and you feel she can handle it, which gives you that bit more confidence. I was sick as dog, but she was great!”

On the Solent, with the same spinnaker colours as in ’79. Photo: Nic Compton

An accidental sailor

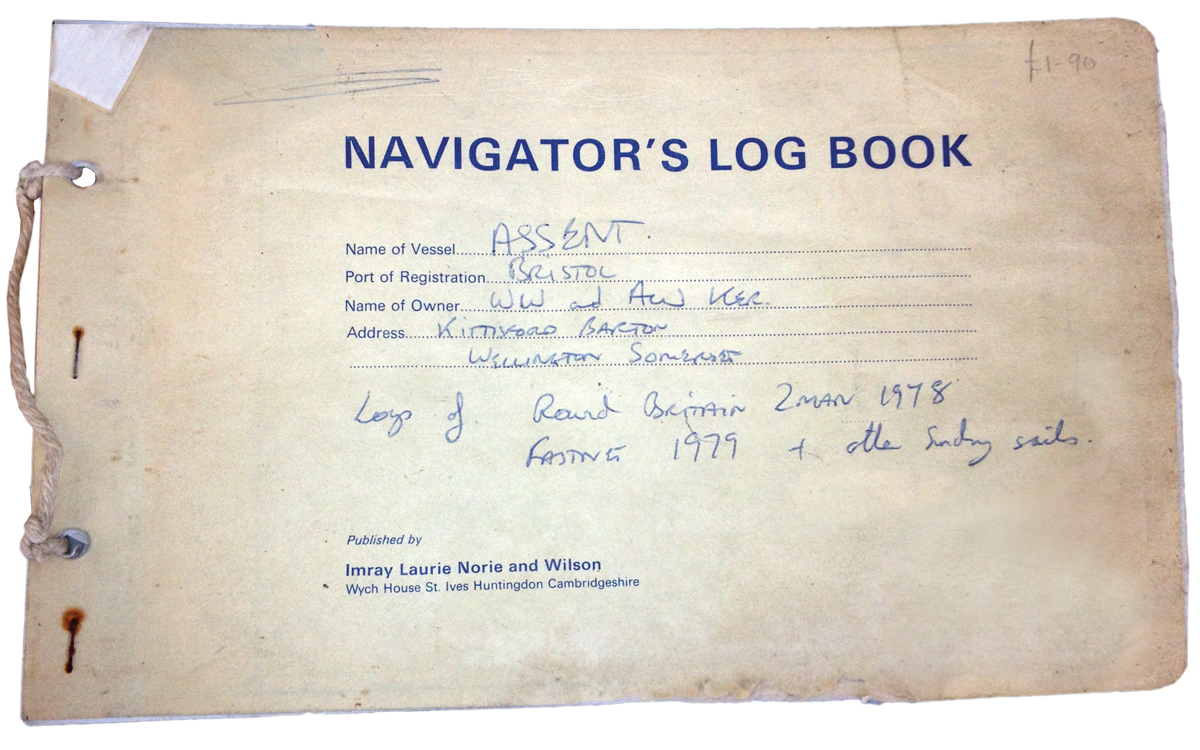

Assent was launched in 1972 as hull No 25, and was originally named Tessa of Worth. She was bought by the late Willy Ker in 1976 and renamed Assent because, so the story goes, he needed his wife’s assent to buy the boat.

Ker was an accidental sailor with a love of adventure. An engineer in the army, he was posted in Kiel after World War II and learned to sail on a fleet of yachts requisitioned by Britain as part of its war reparations. While he was in the army, he attended a university course on mapping and joined a group of volunteers charting the west coast of Canada by horse.

He then organised an expedition with a team of dogs to the Northwest Territories, mapping Great Slave Lake, on the edge of the Arctic Circle. These sailing voyages gave him a taste for remote areas that was to stay with him for the rest of his life.

The programme cover of the 1979 Fastnet Race, which Assent won in class

But Ker also had a competitive streak, and a year after buying Assent entered the 1977 Fastnet Race with his son, Alan, as crew. Two years later, Assent was back, this time with Alan at the helm and a bunch of his friends, all in their early twenties, as crew. Assent was entered in Class V, the smallest class, which included 14 other Contessa 32s.

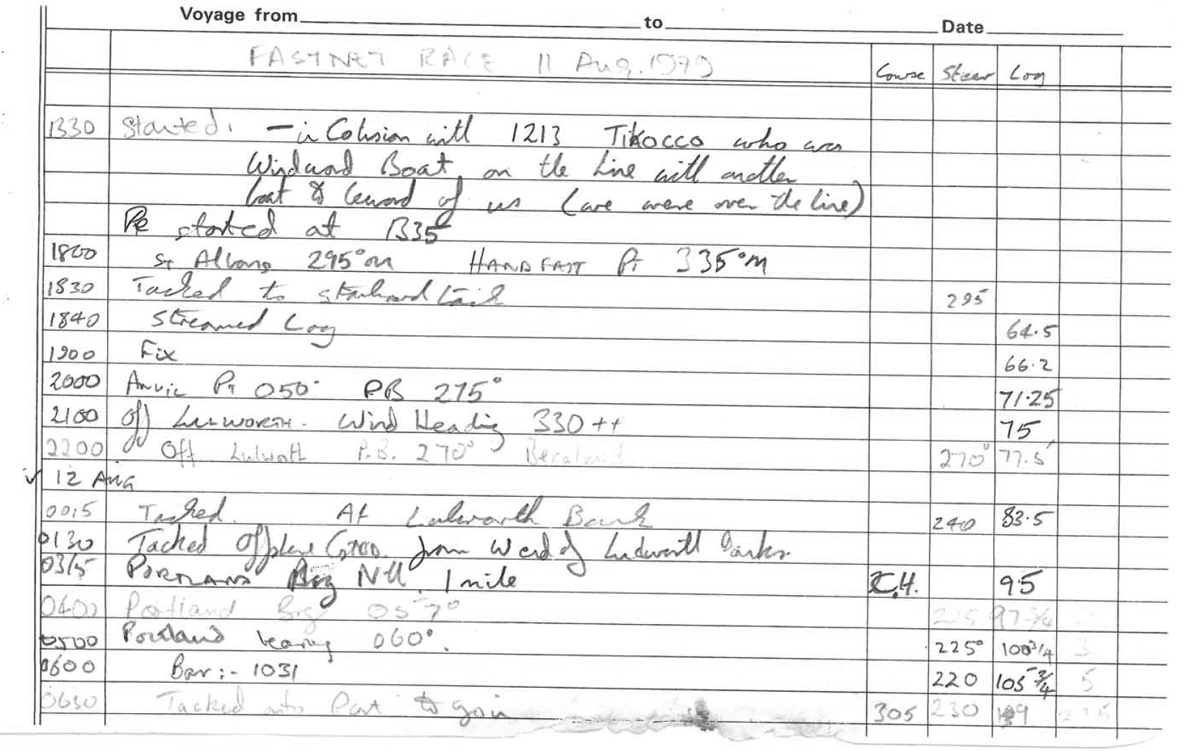

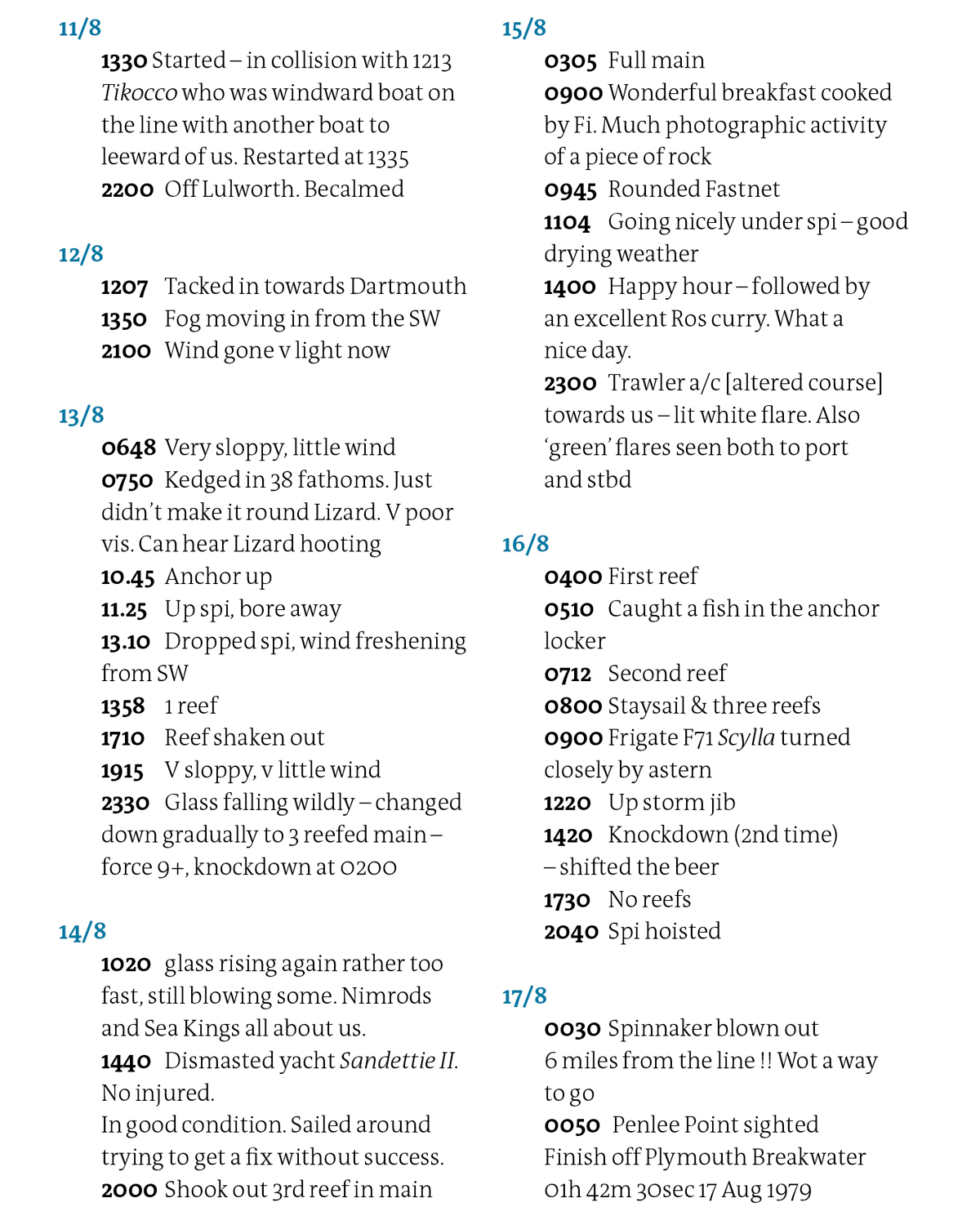

Her race started badly enough with a collision with the French half-tonner Tikocco, and Assent was forced to turn back and restart five minutes later. By that evening, the boat was becalmed off Lulworth while the crew enjoyed a hearty meal of beef stew. It took them another 36 hours to reach the Lizard, where they anchored for four hours in fog waiting for the tide to turn.

It wasn’t until the evening of the third day that the 1755 shipping forecast gave the first warning of a possible gale, by which time Assent was well into the Irish Sea, having passed Land’s End earlier that afternoon.

In his account written straight after the race, crew Gordon Williams wrote: ‘Fiona prepared a fighting supper of spaggeti [sic] bolognaise to which the majority of us did full justice’. It proved a well-timed intervention.

No time for fear

By 2330, the barometer was ‘falling wildly’, the wind was up to Force 9 and Assent was down to triple-reefed main and staysail, according to the ship’s log. Williams was still stitching a rip in the spinnaker when the 0015 forecast warned of Force 10 storm. Two hours later, they had their first knockdown, but even this was dismissed with a joke.

‘It occurred so suddenly that we had no time to fear the consequences,’ Williams wrote, ‘and as the boat quickly righted, with Fiona and I still tied in our places and only a modest amount of water in the cockpit, we shouted to Alan that all appeared to be well and remarked that we could now reckon a knockdown among our sailing experiences.’

Even more remarkable, however, was what followed. After removing the damaged storm jib, Assent’s crew carried on regardless, not just coping with the conditions but, if the log book and Williams’s account are to be believed, positively revelling in them.

‘The sail that followed through the rest of the night after the knockdown was as fantastic and exhilarating as one could expect to encounter in a lifetime of sailing,’ wrote Williams. ‘A half moon had appeared in the clearing sky to light the wild seascape of foaming breakers.

Phosphorescence in the spray was streaming over the sail and cabin top, and the wind was screaming through the rigging and life lines like a pack of coyotes, while all the time the little ship continued steadily on her course to windward with a much easier motion following the loss of the jib.

After climbing up and up each successive sea (reported afterwards to have been 40ft high), we could not help whooping with excitement, and not a little relief, as she crested each summit and slithered down into the next trough.’

The only indication that Assent’s crew were sailing on the edge that night is a significant gap in the log, with no entries at all from 2330 until 1020, apart from a brief reference to the knockdown, which looks as if it was added later. With no anemometer, they didn’t know how strong the wind, and were ‘probably happier as a result’, according to Williams.

Assent wasn’t fitted with VHF radio either, so her crew had no idea of the carnage that was taking place around them. In was only the next morning, when they saw rescue helicopters ‘all about us’ and came across the dismasted yacht Sandettie II, that they began to get an inkling that all was not well.

Assent rounded the Fastnet Rock at 0945 the next morning, with her crew ‘rested and in high spirits’ and, as they headed back to Land’s End that afternoon, they enjoyed a large curry ‘and thought ourselves very well off indeed’.

The next morning, they were back down to triple reefed main and a staysail and that afternoon had their second knockdown, which, as the log book records wryly, ‘shifted the beer’.

Extracts from Assent‘s 1979 Fastnet Race log

First to finish

Assent blasted up the Channel back to Plymouth under spinnaker, averaging 8 knots, only to blow the spinnaker out 6 miles from the finish (‘Wot a way to go!’ says the log).

They crossed the finish line at 0142, and were astonished to discover they were not only first in Class V but were the only boat out of a fleet of 75 in the class to finish the race.

Assent’s outstanding performance – along with the rest of the Contessa 32 fleet, which all retired safely with no major damage – was one of the few positive stories to emerge from the 1979 Fastnet Race.

Assent‘s 1979 Fastnet crew were aged from 18 to 25

In the soul-searching that followed, her seaworthy design was used as the benchmark against which the modern IOR boats were compared and found wanting. Assent soon acquired cult status, and barely a report on the race failed to mention the plucky little racer/cruiser, which succeeded where much grander designs failed.

But the 1979 Fastnet Race was only the start of the Assent legend. After the race, Ker carried on racing, usually with Alan as crew, competing again in the double-handed Round Britain Race (1978 and 1985), three times in the Three Peaks Race, and once in the Transatlantic Race to Newport race (1986).

It was while taking part in the 1978 Round Britain that Willy got switched on to sailing in northern latitudes. After a major refit in 1981, he went back to cruise the Shetland Islands and thereafter followed a haphazard course that would lead ever further northwards.

He ended up circumnavigating Iceland in 1982, and over the next 30 years covered over 100,000 miles, sailing to Norway and Greenland (1986) and then south to the Falklands and Antarctica (1992), back north across the Pacific via Easter Island and Hawaii (1993) to Alaska, Siberia and back to Vancouver.

He then had Assent shipped across Canada on a low-loader, before sailing through the Great Lakes back into the Atlantic and continuing his pilgrimage to Greenland and Iceland. Most of his trips were made single-handed, occasionally accompanied by his wife Veronica or some crew he picked up along the way.

A rare crew joins Ker, who sailed mostly single-handed

Contrary to popular belief, Assent was not strengthened in any way for such extreme sailing and had just the standard Contessa lay up. Her fit-out was entirely functional and almost entirely bereft of creature comforts.

Ker fitted forward facing sonar, to detect icebergs, and an SSB radio fitted with a printer to print out Weatherfaxes. He fitted a 10hp single-cylinder Bukh diesel engine, which was easy to fix and could be hand-cranked, and a paraffin cooker and stove, on the basis that paraffin was available everywhere.

He also shipped three anchors and fitted an enormous windlass on her foredeck, with vast lengths of anchor chain stored in the fo’c’sle, to allow him to anchor the boat in deep water.

Willy Ker sailing Assent off Anvers Island on the Antarctic Peninsula

Ker refused to carry a liferaft, on the principle that if he got into trouble he would rather rescue himself than drift around waiting for help to come. Instead, he had an inflatable dinghy with a rig specially made, complete with a double skin to guard against possible attacks by leopard seals – the only thing he seems to have been afraid of.

He also refused to fill the boat’s tank with tap water, which he thought was “absolutely disgusting”, preferring to collect water straight from glacier streams.

His only concession to human frailty was a small doghouse over the main hatchway – apparently made from an aircraft canopy from an old fighter plane – under which he spent most of his time while at sea.

Ker’s nav station on Assent

Ker’s exploits didn’t pass without notice, and in 1983 he was invited to join the Royal Cruising Club (RCC), an extremely select organisation whose alumni include the likes of Bill Tilman, Miles and Beryl Smeeton and Francis Chichester.

His voyage to Greenland in 1987 – when Assent became the first yacht to sail into Grise Fjord, 850 miles from the North Pole – earned him the RCC’s Tilman Medal, and he was awarded the Cruising Club of America’s Blue Water medal.

Finally, in 2011, Ker made his last voyage on Assent on a trip to Greenland, still sailing single-handed, despite his 85 years. After suffering a heart attack during the trip, however, he was finally persuaded to hang up his sailing boots and return to the UK by plane.

His son Alan sailed the boat home, and put her on the market. Although Ker consented to the sale and was delighted when Kit and Jessie asked to buy her, it must have been like losing a limb for him.

Kit and Jessie Rogers, current custodians of Assent

Functional and unfussy

Back in Lymington, Kit is lighting the paraffin cooker to boil some water for tea. He has a love/hate relationship with the cooker, which is considerably older than the boat, and has been known to use a gas flamethrower to get it going. But wife Jessie was adamant it had to stay.

“It’s part of the story of the boat,” she says. “Willy had it for 40 years and lived on the boat in extreme conditions with only basic equipment. Now we’ve pimped her up with new gear, it felt a bit pathetic if we couldn’t even manage a paraffin stove!”

Since Kit and Jessie bought Assent, the yacht has indeed been extensively updated. She now has new sails (two sets: a Vectron suit for cruising and a carbon suit for racing), a new boom, self-tailing winches, and the running rigging now leads back to the cockpit.

Kit lights the original 1920s paraffin stove fitted by Willy Ker. Photo: Nic Compton

The hull has been resprayed and, below decks, the fo’c’sle has been reinstated and the cushions reupholstered – though Ker’s sturdy, non-standard lee cloths remain. She now has VHF radio and a chartplotter instead of SSB and radar.

Yet, stepping on board Assent, she still feels supremely functional and unfussy, with her bare wood trim, her original mast complete with sturdy mast steps, and her unsprayed deck still bearing the battle wounds of her many voyages.

Far from being pimped up, it feels as if the spirit of her past had been respected. I suspect Ker would have approved of everything the Rogers have done.

Reupholstered, but the sturdy leecloths are the same as ’79. Photo: Nic Compton

“I still feel it’s not really our boat,” says Kit. “It’s still Willy’s boat, and we’re just interlopers. There was clearly a relationship between Willy and Assent that can never be replicated or repeated.

“But we are starting to have our own adventures on her – not on a level with Willy’s, but exciting enough for us. We came first out of 28 Contessa 32s in the Round the Island Race last year. And it’s cool that she’s going to do the Fastnet again.”

It’s tricky taking on a boat with such a massive history, but if anyone can give her a new future that respects her past, it’s the Rogers. As for the Fastnet Race, they’ll be just happy to get around the course and have some fun along the way, just as their predecessors did in 1979.

And if the going gets tough, they’ll have the comfort of knowing that Assent has been through it all before – and much, much more besides.

Assent finished the 2019 Fastnet Race in a time of 5 days, 14 hours, 51 minutes, 25 seconds – placing 30th out of 37 finishers in IRC 4B.