Sam Fortescue reports on the latest developments in autonomous boats and self-sailing technology, which is ready to be deployed in a variety of uses from weather monitoring to shipping

‘Vessel not under command’ looks set to take on a new meaning, with the race to develop a new generation of autonomous boats sailed by artificial intelligence (AI). But what will it mean for other water users?

Today we’re all familiar with the concept of autonomous vehicles. Self-driving cars are the next development frontier, and the tools needed to make them a reality are being intensively tested by some of Silicon Valley’s biggest tech firms.

Less well known is the similar trajectory being followed in the marine industry. So-called unmanned autonomous vehicles, or marine drones, are attracting research interest from everyone from backyard inventors up to engineering behemoths like Rolls-Royce.

They come in all shapes and sizes, with intended purposes varying from meteorology and oceanology, to cargo, surveillance and defence. From the outside, some resemble normal sailing multihulls.

You might never realise there is no human aboard Artemis Technologies’ self-sailing cat, for example, with its 50-knot top speed. The Belfast-based company has based its design for a 45m-long Autonomous Sailing Vehicle (ASV) on technology developed for the 2017 America’s Cup.

Artemis Technologies’ autonomous boat design is based on the 2017 America’s Cup catamaran. Photo: Artemis Technologies

With two fixed wing sails, the catamaran rises up on four foils and hits top speed in just 20 knots of wind. Regenerating propellers on two of the foils charge a large battery bank on board, and that harvesting of energy brings the boat speed back down to 30 knots.

In lighter 8-knot winds, the boat still foils at 20 knots, and electric motors spin propellers that bump the speed back up to its optimum 30 knots. Artemis believes it can be used as a constant-speed commercial vessel for delivering cargo.

Meanwhile, in Plymouth, a consortium including IBM is testing a new Mayflower, a 15m power trimaran studded with solar panels, that should be capable of operating independently for months at a time. It has a top speed of 10 knots achieved with an electric motor drawing power from batteries topped up by solar.

The purpose of the boat is to collect oceanographic data, with sensors on board collecting information on marine mammals, ocean plastics, sea-level mapping and maritime cybersecurity.

See and avoid

The sheer size of some autonomous boats, and the astonishing speed of Artemis’s ASV, highlights the need for safe navigation. Such vessels carry a plethora of collision avoidance systems. While AIS technology has revolutionised collision avoidance over the last decade, it is not universally adopted among fishing vessels or yachts.

Inshore, where marine traffic is at its most dense, many dayboats will lack even a radar reflector. Other solutions, therefore, were required.

Mayflower, computing giant IBM’s autonomous vessel. The 15m boat is scheduled for a maiden voyage Atlantic crossing in April 2021. Photo: Tom Barnes

On Mayflower, computing giant IBM has installed its PowerAI Vision technology to crunch the inputs from onboard cameras that use both normal and infrared light.

In the development phase, so-called ‘deep learning’ is enabling the computer to spot navigational hazards from buoys to floating debris.

This complements radar and laser range-finding to help the boat’s software decide on the best tactic for avoidance. “We’re testing the system, but it is designed to be COLREG compliant and should spot things as small as a man in a rowboat and be able to avoid it,” said Brett Phaneuf, co-director of the Mayflower Autonomous Ship project.

Article continues below…

Torbjörn Törnqvist, head of Artemis Racing – the quiet man of the America’s Cup

You have to look carefully to spot Torbjörn Törnqvist. Wearing identical gear to the rest of his crew and listening…

Crew safety: Lessons from the aviation industry

The safety and wellbeing of both crew and vessel are the primary responsibility of any skipper. Without exception every crew…

“It is programmed to detect and identify all manner of marine objects from many types of ships and boats, to buoys and kayakers. It understands how they behave and can predict movement and act to navigate in and around them.”

In principle there’s no limit to the number of objects it can track. But in the greatest traffic areas inshore, there will be a high bandwidth data link which will enable a human to step in to make decisions for the Mayflower if necessary. “There will always be a low-bandwidth satellite connection so that we may assist the vessel should it ask for help. Its prime directive is ‘don’t hit anything’,” added Phaneuf.

The maiden voyage has been postponed until mid-April 2021, when Mayflower will attempt to become one of the first full-sized autonomous ships to cross the Atlantic. Once the technology is proven, it has myriad potential uses.

Autonomous technology means a single landbased captain could eventually be in command of thousands of tonnes of shipping all around the world. Photo: Rolls-Royce

The race is on to develop commercial vessels with no humans aboard, only remote oversight from someone in a control room keeping an eye on dozens of vast container ships. Rolls-Royce was looking into just this before it sold its marine division to rival Kongsberg.

The company believes the first steps towards using remote-controlled coastal ships will be taken in the middle of this decade, with fully autonomous vessels coming at least 10 years after that. “Autonomous shipping is the future of the maritime industry,” explained Mikael Mäkinen, former president of Rolls-Royce’s marine division. “As disruptive as the smartphone, the smart ship will revolutionise the landscape of ship design and operations.”

The military, too, hope to use the technology to remove vulnerable humans from tedious or dangerous frontline duties, including surveillance. The Royal Navy has earmarked £184m to develop crewless minehunters.

The US Navy has already completed a trial that saw one of its Ghost Fleet Overlord vessels navigate from the Gulf Coast to California through the Panama Canal without incident.

“During this voyage, the vessel travelled over 4,700 miles, 97% of which was in autonomous mode – a record for the program,” reported Josh Frey, spokesman at the Department of Defense.

Small scale autonomous boats

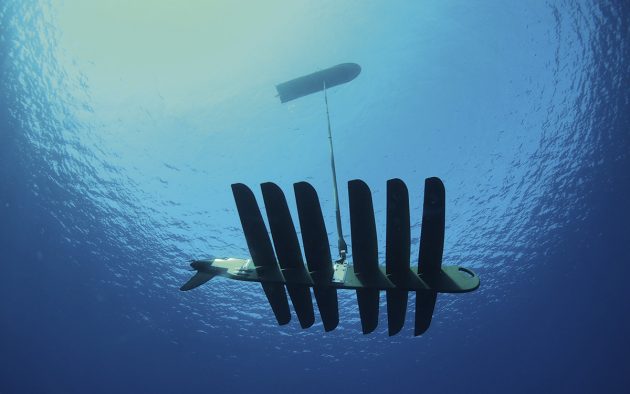

There is also a growing fleet of smaller autonomous craft that can gather a wide range of data. These include the Wave Glider from Liquid Robotics, a 3.05m craft that generates power to operate from 192W of solar panels and a submarine element that harvests wave motion.

As it weighs 155kg and moves at 1.3 knots, the Liquid Robotics team doesn’t consider it to be a navigational hazard. “The Wave Glider is very small and therefore is the one who needs to get out of the way of any other boats,” marketing director Leigh Martins told me. “So, our software uses AIS for vessel detection and avoidance to stay safe.”

Submarine propulsion element of the Wave Glider. Photo: Wave Glider

Two craft closely resembling the Wave Glider were discovered washed up on the Scottish coast without their trailing submarine elements.

Meanwhile, the Sailbuoy under development by the Norwegian firm Offshore Sensing is designed to glance away from collisions.

It measures 2m and weighs 60kg, and its sole means of avoiding collisions are the words ‘Keep Clear’ stencilled onto the balanced wingsail that propels it. “Our solution to this is to make it withstand collisions on the open ocean,” explained CEO David Peddie. “A small vessel like the Sailbuoy does not present any danger to other traffic.”

The company’s website features a video of the Sailbuoy being run down by a small freighter during testing, then righting itself thanks to its heavy keel before bobbing clear.

Sailbuoy is designed to glance away from collisions. Photo: Sailbuoy

These craft are designed to survey their environment, and can hold station like a buoy or travel slowly along a predetermined route.

It has proven a robust approach: Sailbuoy became the first autonomous sailing vessel to successfully cross the Atlantic in the World Robotic Sailing Championship last year.

Saildrone takes a different approach for their autonomous boats. Its Explorer vehicle is larger – 7m LOA, with a 2.5m draught and a displacement of 0.75 tonnes. At this scale, a more robust approach to collision avoidance is required.

While it also uses AIS to spot other vessels at sea, each Saildrone is constantly under the supervision of a human back at mission control in Alameda, California.

Saildrone has also scaled their design up to a hefty 72ft ‘unmanned surface vehicle’. The Surveyor is equipped with deep-sea surveying equipment capable of scanning down to around 7,000m depth, and has an air draught of 18m.

Like its smaller cousins, there is a human in remote control of the boat at all times, to avoid collisions. But Surveyor also bristles with cameras, images crunched by an onboard processor to identify other vessels.

The company plans to put a fleet of 1,000 USVs onto the world’s oceans for a range of missions, from weather monitoring and gathering oceanographic data to patrolling border waters for smuggling and illegal fishing.

Weather spies

One of the most exciting features for sailors will be the real-time weather information autonomous boats can deliver.

Trimtab-controlled wingsail on Saildrone. Photo: Patrick Rousseaux Jenn Virskus/Saildrone

Saildrone founder Richard Jenkins grew up sailing in the Solent, and his company supplied a super-detailed forecast for Cowes Week in 2019, based on publicly available predictions enhanced with ‘secret’ local measurements taken by a Saildrone.

The result was a forecast with a high 200m resolution. In the end the uses for autonomous boats will be as myriad as those for satellites but, as with any new technology, there can be dangers, warns Luc Jaulet, robotics professor at France’s ENSTA engineering school, which is developing the Vaimos autonomous vessel.

As the concept becomes commonplace, the world will have to create suitable rules to keep the oceans safe. “The technology is basically ready, we just have to work out the legislation and then invest in it,” says Professor Jaulet.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.