Phil Johnson and his wife Roxy bought Sonder in 2019. The pair crossed the Atlantic last summer and when Covid hit, decided to cruise Scotland in the autumn

The warble call from a loon broke the silence as we edged closer to shore, motoring quietly through still water. Astern, mountain peaks glowing purple in the sunset faded into the sea. Off our bow, tidal rocks marked the entrance of a cosy lagoon we’d soon be anchored in, just before the crisp evening air settled around our yacht Sonder as we continued to explore in our hasty plan to cruise Scotland.

The bay was shadowed by sheer cliffs of dark volcanic rock, now in silhouette, that thrust high above our mast top, reaching 1,000ft in places. This was Scotland in the autumn, during a global pandemic, and we were all alone.

My wife, Roxy, and I are both in our early 30s and run a small e-commerce business remotely while living on our Cheoy Lee Pedrick 47 Sonder. In August, we sailed across the Atlantic from Massachusetts, with the goal of cruising the warm waters of the Mediterranean, but with European COVID travel restrictions still in place, we opted instead to winter in the UK.

This change in plans set off a chain reaction of spontaneous decisions; the first being an idea to cruise Scotland ‘while the weather was good’. However, it was now the beginning of October, and local sailors we shared our cruising plans with responded uniformly: “The sailing season is already well over!”

Their advice resonated as we sat in our chilly, damp cabin listening to sheets of rain on deck while docked in Belfast. Sonder has spent her life in warm water without a diesel heater, which is a problem since Scotland’s northern latitude nearly matches that of Greenland.

As we hurried to install a heater, friends docked alongside us with European passports tossed their lines and departed for a course south, chasing the waning sun.

Tempting though their plan was, we instead turned Sonder left, sailing into steep chop that slapped her bulwarks as we pushed north out of the Irish Sea.

‘Turning left’ for Scotland proved a great escape for visiting US sailors Phil and Roxy Johnson. Photo: Photo: @sailingsonder

The water of the Scottish west coast isles awes visitors with its icy clear blue, more reminiscent of the Caribbean than anything you might expect to see at this latitude. Its temperature is slightly warmed by the faint remnants of the Gulf Stream, which helps moderate the climate of this archipelago.

This was why, upon making our first landfall and anchoring off the Isle of Gigha, we were surprised to find New Zealand palm trees dotting a bay of white sand beaches scattered between granite boulders.

Cruise Scotland in an Indian summer

In the morning, the sun lit the water brightly right down to the base of Sonder’s keel. Plucky locals nearby leapt into the shallows for an icy swim.

I hugged my morning coffee in the cockpit with a woollen blanket over my shoulders. Perhaps the Belfast sailors were wrong, maybe we were fated to have an Indian summer?

My eye caught the scurried movement of an otter climbing a nearby rock. A little later, several otters were taking turns basking in the sun, as if they too felt the scarcity of this warm morning.

The fine weather held the following day as we broad-reached toward Loch Tarbert on the Isle of Jura.

A peaceful anchorage on the Isle of Mull. Photo: @sailingsonder

Sonder’s full main and 110% genoa scooped the following breeze from our starboard quarter, the seas running down the Sound of Jura just starting to build up as the sound widened towards the Atlantic.

I slid the port jib-car forward, pulling the genoa leech tight and called back to the cockpit for Roxy to sheet out the main a little. The weather-helm eased and Sonder drove forward, unaffected now by the short seas building behind us.

With full tanks and provisions, Sonder weighs nearly 22 tons. Even so, she moves along just fine in moderate airs, carrying over 1,100ft2 of canvas. The designer, Dave Pedrick, cut his teeth at Sparkman & Stevens and brought the same classic ocean-racing philosophy with him when he designed a line of Cheoy Lee cruising yachts.

Her proportions are quite moderate; she has a long keel with cutaways fore and aft and a skeg-hung rudder. The beam narrows towards the stern, which has a slight overhang coupled with a healthy freeboard and moderate sheer.

On this day, Sonder was in her element sailing at over 7 knots through the water. We made quick work of the Jura Sound and soon entered the narrow seaway dividing the south coast of Jura and Islay just as the tidal flow increased in our favour.

Article continues below…

It’s Windy Up North

Violent storms forecast in Scotland

Scotland’s stunning sailing

The west coast of Scotland can't be beaten. It has some the finest seascapes on earth

The high shoreline of Jura dirtied the air, with puffs coming at us from shifting angles. I steered us between the channel buoys, scanning the water’s surface for signs of katabatic gusts coming off the surrounding hills and cliffs while Roxy sheeted the main in snugly.

The tidal stream made up any loss of speed difference and we clocked speeds of up to 13 knots dancing though overflows, eddies and gurgling water.

Sonder dwarfed by the majestic Cuillin peaks in Loch Scavig, Isle of Skye. Photo: @sailingsonder

Around the west side of Jura, Loch Tarbert is a deep, watery scar on the west-coast that nearly severs the island in half with miles of tidal bays and creeks, all surrounded by pristine privately-held wild lands.

We approached an anchorage surrounded by hills of heather and thistle that shone a confetti of bronze in the autumn sun. Statue-like stags were silhouetted on top of a distant ridge, behind which rose the grey twin peaks of Jura, affectionately called ‘The Paps’ for their bosomy shapes.

A few moments later, when Roxy had our anchor set and the engine turned off, an overwhelming silence took over, with only the faint babble from a distant brook and the lap of water rounding stones on the shore creating an ambient soundtrack. This quiet serenity, during the pandemic felt like a calming antidote to our anxieties.

Not far north of Jura is a 5th Century stone abbey that seems inexplicably exposed on the pastures of the Isle of Iona. Navigating this shore requires close attention with many shoals stretching miles off the coast.

Time and tide…

We timidly anchored on the Isle’s north-western tip, in a small white-sand bay exposed to ocean swells in everything but the calmest conditions.

After a wet beach landing with our RIB we made our way through the maze of sheep fencing to find the island’s sole road, a narrow, single track.

It was late afternoon and the shadows cast wide as we walked south the mile or so to the Abbey, now

crystal clear water makes

hull and keel checks a doddle. Photo: @sailingsonder

showing distinctly against the grey granite of the island’s few rocky moraines. Ancient stone walls which lined the road parted to envelop the Abbey and its town.

The Abbey has drawn monks, pilgrims and tourists for hundreds of years, but today we were outliers as visitors among the resident sheep and cattle.

As the hue of sunset faded we walked in silence back to Sonder, finding our path to the beach down a steep dune. Our dinghy was somewhere in the dark up ahead, hauled well up on the tide line. A few minutes later we found it, filled with saltwater and many, many pounds of sand.

The placid sea had somehow still managed to swamp it. Our biggest mistake was not even having a simple bailer in our dinghy, this time a shoe having to suffice. This was the first of several lessons the tide would teach us.

A Storm Brews

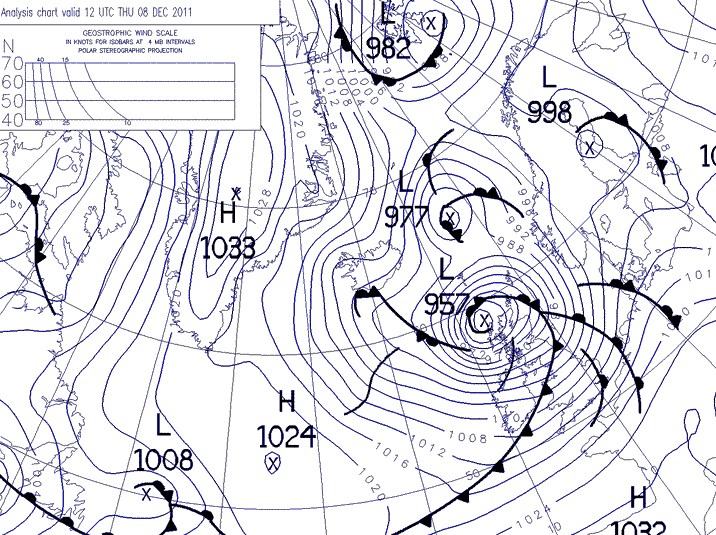

In the autumn, low pressure systems sweep across the North Atlantic, often bringing strong winds and big seas to the west coast of Britain. South-westerly gales are common, but occasionally highs buffer these storms, turning sailing into a finely tuned game of hide and seek, dodging in and out of protected anchorages before another system rolls in.

As we enjoyed an extraordinary Indian summer, it was easy to forget what normal weather was supposed to be like at this time of year.

A reminder came forcefully in the form of Storm Aiden, which lashed the west coast over Halloween. As the storm headed our way, we sailed Sonder beside the Isle of Mull under double-reefed main and partially furled genoa.

Sheets of rain blew down from the Monroes on Mull channelling into choppy waves in the narrow seaway. A Caledonian MacBrayne ferry was our only companion while Sonder heeled deeply as she dug into the chop, and we had to take several tacks across the channel.

As the forecast continued to deteriorate, we decided to make a rare trip to a marina, tying up at Dunstaffnage in Oban. I looked over to our neighbours in the next slip and saw the skipper tying his ninth dock line, every one of which was carefully fitted with rubber shock bands. “Is this weather typical for this time of year?” I asked. “Aye, we get a few each year but I’ve never seen nuthin’ like this,” came the response.

Tobermory’s houses are as colourful as a rainbow. Photo: @sailingsonder

The following morning Sonder started to buck on the hammerhead with the wind screaming above 60 knots. Borrowing muscle from our bemused neighbour, we heaved and pulled to fix the lines, as if handling a wild beast.

I could see our inflatable fenders blowing sideways in the gusts, dangerously exposing Sonder’s hull to the dock. It was then that I made a comically late decision to find suitable fenders at the local chandlery.

The storm surge was by now pushing green water over the quay. While Roxy stayed behind to fend off Sonder, I set off for the chandlery. After walking in with water streaming off my foulies I asked a kind lady behind the counter for her heaviest fenders, to which she replied, in her thick Highlander accent, “Well it’s a little late for that don’t y’h think?”

I borrowed a lifejacket from an insistent Coastguard man for my return trip to Sonder, using the shiny fenders as extra buoyancy to fight the torrent of water and wind. It was another half hour of battling with fenders and lines before Roxy and I could return to the warmth of our dry little cabin to thaw out.

When the sun broke through the clouds the following morning, we could see snow on the mountainous horizon. News arrived of lockdown measures in England for all of November, swiftly justifying the postponement of our wintering plans in the Solent.

By now we were entranced by the timeless beauty of this coastline, and all too easily lured by descriptions of anchorages further into the Sea of The Hebrides.

So, donning every piece of warm clothing we owned and filling a hot water bottle to warm our fingers against the biting cold, we set off north, alone again.

Plockton Harbour – the Gulf

Stream creates a microclimate. Photo: @sailingsonder

Loch Moidart appears like a two-tailed snake on the chart, curled tightly around a wooded island.

Two days, and some 50 miles of upwind tidal sailing lay between us and the inner anchorage, situated at the foot of a 15th Century castle that loomed large above Sonder’s spreaders.

Called Tioram, this idyllic stone ruin is set on a large grassy berm guarding the inner loch – or rather, that’s the view we were greeted with in the morning, having actually found the anchorage in pitch dark. Like buying fenders in a storm, I don’t recommend night-time loch navigation.

Night-time nav

The night before, utterly frozen from a long day exposed in our open cockpit, we slipped past the narrow rock-strewn entrance into Moidart as the last of the evening light faded behind us.

Roxy stood on the bow with our most powerful flashlight to spot buoys and I focused on the GPS running Antares charts: a local and, thankfully, highly accurate sounding of anchorages on the west coast. In the tight turns of the channel and with no moon there were no reference points on land or water, and when my eyes followed the beam of the flashlight it always appeared as if we were headed towards shore.

I could sense Roxy’s nerves being quietly tested as we motored past exposed rocks close enough to touch with a boat hook and, more than once, the GPS briefly glitched from signal interference in the narrows. But, with the current and lack of sea room, there was no turning back.

Finally, after nearly three miles of this recklessness, the channel opened into a pool and we dropped our anchor, relieved, a bit lucky and ready for bed.

The following morning the aroma of my coffee mingled with the scent of salty evergreens growing in abundance on shore. I hoisted our Google Fi phone up a halyard on the mast to catch a tenuous signal while Roxy made calls from her laptop – we’re both never working and always working.

In the afternoon, we stole away for a hike up a small mountain to the east. The trail threaded its way around large boulders just above the tide line, then turned abruptly, traversing up a steep slope as beech and evergreen trees gave way to fields of native grasses.

The spectular Isle of Gigha; white sand beaches and turquoise waters reward sailors who explore Scotland’s west coast. Photo: @sailingsonder

As we climbed the calls of seabirds gave way to the faint rumbles of an underground spring nearby and the soil under our feet became a dense black peat that oozed around our boots. At the peak, bronze hilltops multiplied in mirror images out to the horizon broken only by a single sharp line of cobalt; the Atlantic to the west.

Back inside Sonder’s teak cabin, our heater slowly won the battle against the damp air. Roxy lit candles on our dinette table, a new nightly routine to add some much-needed ‘hygge’ indoors as Sonder swung back and forth at anchor between gusts that whipped down off the dark mountains of Skye during an evening squall.

I finished cooking a chowder, filling the cabin with scents of smoked paprika, heavy cream and salt, before we sat down to watch a movie, turning the soundtrack up to drown out the weather grinding away above our heads.

Sometime later, when the film finished, I stood up to realise we are heeled over motionless in the water. Checking the depth sounder confirmed that Sonder’s keel must be on the seabed. The tidal range in Portree, the main fishing village on Skye, is around 15ft, which makes anchoring a challenge on the narrow shelf lying parallel to the shore. The bottom is mud and there was little we could do but try to sleep in the frothy conditions.

By morning, the weather had improved some but our situation hadn’t. Peering out the port side as I ground some coffee, I was shocked to see sheep grazing on a narrow towpath a mere 100ft away. Did we drag our anchor after being marooned during the low tide? More luckily still, it seems we dragged 1,000ft from our set point, our drift following the shelf and barely keeping us off the rocks.

Fairytale endings

The forecast for the following week was bleak, showing a tentative window before December to sail south to our winter berth in the Solent. The decision was inevitable; our six-week cruise of Scotland was coming to a close.

Tidal flows, storm conditions, weather prediction, complex inshore navigation – we’d used nearly every skill in the sailor’s arsenal, together with a bit of luck, to thread our way up the west coast.

It’s bone-chilling standing watch at the helm while endless rain and bitter wind forces its way up the

Enjoying the high life off the beaten track on Skye. Photo: @sailingsonder

sleeves of your foulies, or wrestling with the cold metal of the anchor chain to attach the snubber while the sun sets at 4pm.

But the struggles we had with Mother Nature, and there were plenty, did not on the whole detract from our experience. The difficulties instead helped illuminate the stark contrasts of Scotland’s west coast.

It’s the smells of chilled sea spray against warm peppery peat smoke, the shards of black Cuillin rock against soft lambswool, and the vast expanses of silence broken by the roar of a storm. This is a land of extremes.

Undoubtedly, sailing Scotland in the peak of summer must be lovely, but I wouldn’t trade it for the fleeting opportunity we had to take Sonder north, while the days were getting shorter, to discover empty anchorages among the hills and sheep. Now, when the time next comes for a hardy adventure, we know there’s a place to find nature in its most raw and timeless form.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.