After six years of bluewater cruising, Terysa Vanderloo and partner Nick Fabbri enjoyed a slow cruise through Brittany on their final passage home

The sun lingered low in the sky, casting a golden glow over the sandy island of Höedic. The small south Brittany harbour is home to three large mooring balls, around which yachts rafted together in a circle, with bows attached to the ball and sterns facing outward, like the petals of three flowers.

In our cockpit, Nick strummed his guitar and I sipped on a glass of rosé, as we watched the late afternoon rush of sailors entering the harbour and trying to secure a place.

Sometimes a single-handed sailor would tie up with the practiced ease of decades of experience, leaving us embarrassed at our own clumsy efforts earlier in the day.

Other times, yachts would arrive full of enthusiastic yet unskilled crew, and after watching several messy attempts at securing themselves, we’d reflect that perhaps we didn’t do so badly after all.

Seagulls wheeled overhead, swimmers splashed in the water, and dinghies nosed their way between the rafted boats and the floating dinghy dock. The ferry blasted its horn and, in what seemed an impossible manoeuvre, executed a tight turn in the packed harbour, before steaming away, leaving yachts rocking in its wake.

Secluded bay on the island of Houat. Photo: Hemis/Alamy

This was our evening’s entertainment, and after six years of living full time on our Southerly 38, Ruby Rose, the simple pleasure of relaxing in our cockpit after a day of sailing in the sun, watching the harbour activity, was the very epitome of why we chose this cruising lifestyle.

But, this being the summer of 2020, those moments of peace were made more poignant, both because of the price we’d paid to enjoy that little bit of freedom, and because it was tempered by the knowledge that this reprieve was temporary, the future uncertain.

For us it was particularly bittersweet, as this was our final season on board Ruby Rose: we were sailing her back to the UK to be sold so we could prepare to move onto a new 45ft catamaran.

Two months previously, in May 2020, Nick and I had been desperate to get back to Ruby Rose, which was waiting patiently for us in La Rochelle on the Atlantic coast of France.

Yachts rafted to a mooring buoy at Höedic. Photo: Photononstop/Alamy

We, like many liveaboard cruisers, had spent the winter alternating between living on board in the marina, doing all those little jobs that you never seem to get to the bottom of, and travelling home to see our families.

For me, home is Australia, but as the pandemic hit and international borders started to close, we made the last minute decision for Nick and I to converge at his parent’s house in London.

When Nick left Ruby Rose, the French border slammed shut behind him, swiftly followed by the UK going into hard lockdown. Our boat is our only home and we, like many others, were stuck with no way of getting back to her.

Article continues below…

Cruising in Brittany: its warm weather, golden beaches and handy marinas take some beating

Peter Cumberlidge cruises the coast of north Brittany and investigates a slower pace of life among the many island anchorages

Sailing Biscay: Top tips for a safe and smooth crossing of the notorious bay

Biscay has a fearsome reputation and for many sailors, it is their first taste of bluewater sailing. Distances may not…

Ten long weeks later and both the UK and France were beginning to ease the hard lockdown restrictions. We booked train tickets and arrived at St Pancras station armed with sheaves of paperwork proving that we lived aboard and were merely trying to return home, hoping that Border Control would understand our unusual situation.

Luckily, after some brief but nerve-wracking discussions, we were allowed into France and that afternoon, feeling lightheaded with relief and joy, we arrived back aboard Ruby Rose. A couple of weeks later the local restrictions eased further, allowing us to start sailing again.

Quite to our surprise, it seemed that we’d enjoy our final sailing season in France after all.

La Rochelle’s busy harbour. Photo: Karl Hendon

Nick and I had sailed from Kent to La Rochelle and back two summers in a row before we made the move to full-time liveaboards. Since then, we’ve sailed the Mediterranean, crossed the Atlantic to the Caribbean, cruised the Bahamas and the US East Coast, and even taken our boat through the French canals. Yet the Atlantic coast of France, in particular north and south Brittany, remains our favourite cruising ground.

Great cruising in Brittany

Picturesque islands, sandy beaches, winding rivers, inland waterways, challenging yet enjoyable navigation, historic harbours, and, of course, the sheer Frenchness of the area, from the unparalleled food and wine to the local passion for sailing, make this cruising ground surely one of the best in the world.

And if it rains every now and then, or you misjudge your tidal calculations and end up pushing a foul current, or if you get caught out by an Atlantic low pressure system, well, that just adds to the fun – or so I tried to convince Nick as he lay in the cockpit, overcome by seasickness one grey and lumpen day as we beat into the wind and rain in the Bay of Biscay.

Knowing that we’d soon be saying goodbye to Ruby Rose, we couldn’t think of a better area to enjoy our final cruise on her.

We left La Rochelle one calm, sunny morning in early June on a glassy sea with barely a breath of wind. Having been cooped up for months, we were among dozens of boats exiting the marina and heading for one of two nearby islands.

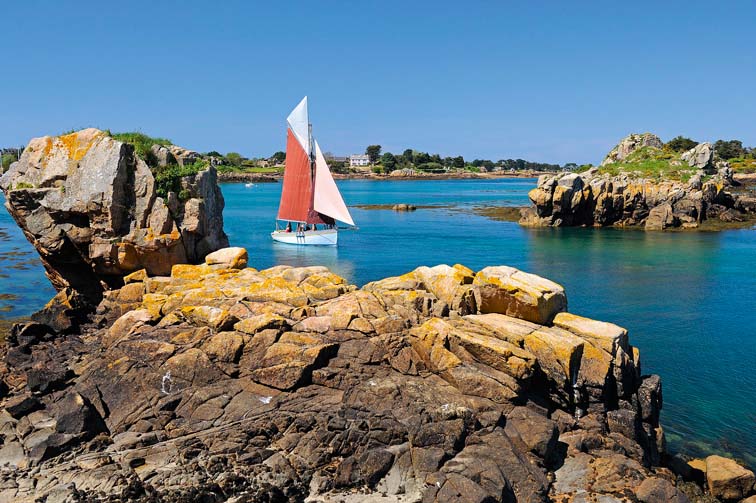

A scenic passage between Île-de-Bréhat and Île Beniguet

Île de Ré is slightly to the north, and we’d visited during our previous cruises. It’s a delightful sandy island, easy to cycle around and home to Saint Martin-de-Ré, a charming medieval port with a locked marina that is accessible at high water only.

We loved Île de Ré – it’s impossible not to – but decided this time to head to Île d’Oleron, another island slightly to the south of La Rochelle, as we’d never been there before.

It was only an 11-mile journey, and we persevered with the sails for as long as we could, but when we dropped below one knot of boatspeed, we capitulated and turned the engine on. Even so, we were both wearing big grins, unable to believe our luck that we’d been able to get back on board and could start exploring once again.

The following week was spent riding our bikes around Île d’Oleron, visiting the market, and occasionally enjoying a coffee sitting in the sun in the little village square. We seemed to be the only foreign cruisers, a trend that unsurprisingly continued well into the summer, and we loved being totally immersed in the local French culture.

Tricky biscay

Having spent those first few weeks back on board closely studying the forecast, we quickly realised that getting north wouldn’t be quite as straightforward as we’d thought.

We had done this passage before but it was years ago and with hindsignt we’d forgotten about some of the tricky local weather patterns in the Bay of Biscay. Essentially, to leave the Bay of Biscay we had to sail in a general north-west direction to get to the Raz de Sein, one of two tidal races on the far north-west corner of France (the other, the gateway to the English Channel, is the Chenal du Four).

Lighthouse of La Teignouse, between Quiberon and Houat. Photo: Hemis/Alamy

The winds entering Biscay, however, would often curve south, following the direction of the coastline. Southerly winds seemed to be rare, and in south Brittany we were often at the mercy of the strong afternoon westerlies which, of course, meant that any westing had to be achieved in the early morning light airs.

In short, we had to pick our weather windows carefully and be flexible with regard to our timing. On any days when we got any south or west in the wind, we left, whether we wanted to or not.

Heading north, we stopped at Les Sables d’Olonne, a seaside town with a big fishing harbour and home to several boatbuilders, not to mention a supremely well-protected marina (famously the home of the Vendée Globe). After being port-bound for over a week due to an Atlantic low, we then set off for Île d’Yeu.

This was the passage where Nick was afflicted with seasickness, something that seems to be a trend. The last time we sailed here we were similarly port-bound in Sables d’Olonne and upon leaving encountered uncomfortable seas that put Nick out of action that day too. It’s a good thing Île d’Yeu is so delightful and well worth a few hours of misery.

From here, South Brittany, surely the gem of Atlantic France, beckoned: the flat and sandy islands of Höedic and Houat, the lush and mountainous island of Belle Île, as well as the charming river Vilaine and the vast inland waterway of the Morbihan, home to hundreds of small islands and the picturesque medieval city of Vannes.

This corner of France alone could easily entertain any cruiser for an entire summer. Indeed, we seriously wondered if we were making a mistake in selling Ruby Rose and buying a catamaran to cruise the tropics.

It didn’t really matter what the weather was doing, there were anchorages and harbours to provide protection against any wind and swell direction.

If there was any inclemency in the forecast we simply went into the Morbihan and made our meandering way up to Vannes, or sailed further east, through the lock, and into the peaceful Vilaine (although I must admit the hull slap on the visitors pontoon in the otherwise delightful village of La Roche-Bernard was enough to drive me to distraction – though at €80 for an entire week’s mooring it was worth bearing).

Heading west

Eventually it was time to force ourselves to move west. We had a favourable forecast and moved swiftly along the south Brittany coastline, stopping over in Port Louis in the Lorient and Concarneau.

Entrance to Le Palais on Belle Île. Photo: Boris Stroujko/Alamy

We’d previously visited the Îles de Glenans, an archipelago of uninhabited islands south of Concarneau, but with gentle easterly winds and a tidal race to catch, didn’t have time to revisit them this year.

Instead, westward we went, anchoring overnight at Audierne – where we were woken by a very welcome knock on the hull from an enterprising local who was making the morning rounds in his dinghy, selling baguettes, croissants and pain au raisin – before going through the Raz de Sein.

Despite the Raz de Sein’s intimidating reputation, we’ve always timed our passages very carefully and transited the tidal gate on calm weather days.

Like our previous experiences, sailing through the gate was uneventful, which is just how we like it. From here we explored the craggy Baie de Dournanez, where the coastline was even more wild and beautiful than further south: steep cliffs overlooked wide, sandy beaches while a world of hidden coves and bays beckoned.

A stop in Camaret-sur-Mer is a must, and with an expanded marina there’s room for many more boats than when we first visited. The managers have a hands-off approach when it comes to allocating berths, and it’s down to the skippers and their crew to find somewhere suitable.

Despite the fact that this marina seemed to be at capacity, if there’s one thing I’ve learned from cruising in France, it’s that there’s always room for one more. We ended up rafted against another monohull and stayed for several happy days.

Camaret-sur-Mer is an almost mandatory stopover for sailors going both north and south between the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel as it’s not only reasonably well protected and well placed geographically for breaking up the two tidal races, it’s also an utter delight.

Morbihan has many picturesque places to visit. Photo: Boris Stroujko/Alamy

The cliff walks are spectacular, the beaches breath-taking, and the food everything you’d expect from a seaside fishing village in Brittany. We could have spent an entire summer there, watching the comings and goings, wandering the bars and restaurants of the village in the evenings, and taking brisk hikes along the coastline during the day.

However, the summer was almost over and, more worryingly, Covid cases were on the rise in France. We hastened north.

Our Chenal du Four tidal race passage was as straightforward and enjoyable as the Raz de Sein: we had one of those rare, perfect sailing days with warm sunshine, 15 knots on the beam and flat seas.

The Raz de Sein has a fearsome reputation but can be easily negotiated in calm weather with the right tides. Photo: Hemis/Alamy

We caught the north-setting tide through the gate and soon were back into the English Channel after five years away. It was quite surreal to be so close to the UK and approaching the end of our chapter aboard Ruby Rose.

We could have sailed north across the western approaches and made landfall in Cornwall or Devon, and indeed we were very tempted to do that. However, unwilling to leave Brittany just yet – ‘Just one more gallette and cider!’ – we stayed in France and started to make our way east.

The north Brittany coastline is even more rugged than that surrounding Camaret-sur-Mer, littered with rocky outcrops and islands which were initially quite intimidating to navigate. However, the area is also spectacular, each rock-strewn landscape slowly coalescing into an island, a harbour, or the entrance to an estuary.

Years ago when we first sailed this coastline there was no good option for visiting Roscoff in a yacht. Now, there’s a brand new marina with excellent protection, wide fairways, and a modern bar overlooking it.

Camaret-sur-Mer. Photo: Eduardo Fonseca Arraes

The air is cooler than further south, and the day we explored the town of Roscoff it was blanketed in fog, the medieval seaside fishing village taking on a mysterious air which only added to its beauty.

Pink granite coast

We then sailed east again, timing our passage with the tides to carry us to Île-de-Bréhat. After rounding the north side of the island to arrive at the rose coloured rocky anchorages on the south-east corner, which changed in dimension with every passing hour as the lapping waves rose and fell with the tide, obscuring and in turn revealing the pink-tinged granite rocks that encircled the island.

Heading ashore, we walked the narrow lanes to the village in the centre of the island, picked up a baguette and some supplies, and then made our way back, getting lost a few times but eventually finding our way to the pebbled beach off which Ruby Rose was anchored.

On the morning of our departure to Jersey, the sun was a blurry red orb, the sea and sky a milky pink with no distinct horizon. Heavy with regret, we raised anchor and made our way out of the anchorage, knowing that although the next chapter of our liveaboard cruising lives would take us far away from here, Brittany is the cruising ground to which we’ll always, eventually, return.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.