Sailing the northwest passage in a 43ft gentleman’s cutter was the fruition of years of planning for Will Stirling

Integrity set sail from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, on 1 June bound for Alaska via Greenland and Arctic Canada. It was a Thursday. With naval superstitions rife among the crew and the trouble of folklore’s HMS Friday, there was no option to delay.

Having misdiagnosed one of several narrow channel entrances passing between two low lying islands and out onto the sea, we almost encountered the sea bed within a mile of departure port. Running aground on mud is not too bad, rocks tend to have a more serious impact.

Having overseen various sailing mishaps and therefore accustomed as I am to general embarrassment and small scale humiliation, a call for help so close to the start would have been a little difficult to wear with grace. But the misadventure was soon forgotten and by dark we were roaring up the Nova Scotian coast.

The crew of four divided into two watches; one to steer and one to pump. By the time that the small electric bilge pump had packed up and the rebuilt engine-driven emergency pump had broken down, a rota of the off-watch team clearing the well once every 10 minutes with the manual pump was in place. By the end of everyone’s first night out at sea, we’d done 20 miles of the 6,000 ahead. There was no sickness on board, but a general distaste for the job in hand.

The route

Thorough trials

Integrity is a replica of a Victorian cutter circa 1880, designed and built at our small Plymouth shipyard in 2012 in seasoned English oak, copper and bronze with a heavy dose of lead underneath. Five years of use in all seasons within hailing distance of the shipyard had allowed us to test and improve the boat, but also to teach ourselves how to sail her.

Following the extended Plymouth-based sea trials, Integrity spent five years in Iceland with a number of summer voyages to Jan Mayen and East Greenland, while the Northwest Passage expedition was set for 2023.

These years based in northern Iceland brought a different type of boat preparation and training. Each successful voyage cultivated a deepening assurance in the qualities of the boat and the crews and, crucially, experience of navigation in ice. We also learned about ourselves; having to deal with the boat and manage our own behaviour when tired, cold, hungry and at times frightened.

After each voyage spares and repairs were considered in two categories: the immediate in order to make the boat safe after an incident, and the onward in order to have the ability to continue a journey. We had to be sure of our own ability to service, maintain and repair the boat. Time in Iceland before and after each excursion also brought another element of great value: friendships with those familiar with the Arctic and the benefit of their advice.

Having departed Iceland for one final sojourn in East Greenland, we sailed on south from Cape Farewell, reaching Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, late in the season. This was a journey in the wrong direction but felt worthwhile because we wanted the boat to be in an area of infrastructure and expertise for a thorough winter inspection and refit. The aim was to remove any element of doubt as to the structural condition of the boat where things could not be immediately seen for survey.

Navigating by sextant through the land of midnight sun. Photo: Will Stirling

Lobsters and leaks

Though the boat had been in refit overwinter it regrettably seemed to be in worse condition than when sailed to the Lunenburg yard the previous autumn. The most immediate issue (among a catalogue of grumbles, the most minor of which was my climbing boots having been inexplicably melted in acid) was the refinished topsides, through which the pumping team were able to clearly see and note the dipping heights of the numerous passing lighthouses.

It remained dark, the wind increased, the sea rose, water ingress continued and the gaff jaws came adrift aloft. At this point a meek suggestion was made that we might ‘go in’ somewhere to resolve some of our more pressing problems. On the face of it, this was a sensible proposal. However, with a fair wind and no immediately available harbour, I felt that first we might try to tackle our problems one by one and then reassess.

On we sailed for 100 miles to the rural quay at Fisherman’s Wharf. Supplied with lobsters by the kind fisherman, we set about where necessary, refitting the refit. We reminded ourselves that if we couldn’t sort out the raft of issues that presented themselves, how could we expect to tackle the Northwest Passage?

Walker trailing log measures distance run. Photo: Will Stirling

First ice was encountered in the Strait of Belle Isle, at a parallel latitude with Cornwall and in short order the southern edge of the Labrador pack ice hove into view. Further progress north along the Labrador coast was forestalled by the ice and so preparations were made for the 700-mile passage across the Davis Straight to Greenland.

Leaving Labrador at first light gave us the longest period of daylight to sail clear of the ice. During the first day of the passage, we encountered the southern tip of pack significantly south of its plotted position and skirted around it. The ice lights were rigged before darkness fell.

A little later we came into an isolated patch of loose ice. There was a swell running making the ice dance in the water. The ice density increased within a few moments and it wasn’t clear where to turn in the dark. Just when things were beginning to look awkward, the ice seemed to dissipate and with great relief we were in clear water again.

Navigating through slush ice. Photo: Hugh Coulson

As the days passed and we rotated watches on the tiller, the miles accumulated on the log. Having turned off the GPS before departure, we were consciously engaged in the practice of navigation. In a world where we are surrounded by technology that we do not comprehend, we sought to understand our position on the globe using the evidence around us. A collateral benefit of traditional navigation is to experience the excitement of landfall.

Given the size of Greenland, we could proceed with reasonable confidence in finding the world’s largest island at the end of the bowsprit. It would then be a matter of deciding on which part of the 1,500-mile coast we arrived.Hence, navigation was by dead reckoning supported by sextant sights when the sun was visible. Venus and the Moon also helped but as we proceeded north, night faded into twilight and we entered the land of midnight sun.

After six days at sea the fog peeled back to reveal the snowy mountains of Greenland. We worked our way north sailing among offshore islands. Wildlife spotted included eagles, an Arctic fox, an Arctic hare and one musk rat. With no darkness, sleep patterns became erratic. We might wake at midnight and breakfast at 1600.

On reaching Disko Bay, crew Martyn Oates produced a mini disco ball; a joke of considerably patient gestation. In Disko Bay, ice concentration increased which became tricky with narrow anchorage entrances and grounded icebergs. One anchorage yielded a crop of mermaid’s hair; we played football on a surreal astroturf in Godhavn; and Luke Browne led a short climb on a carefully selected berg. The ice was incredibly hard, but with some nudging and wiggling we made it in time and on time for the first crew change in Ilulissat.

Poling off to release Integrity from pack ice in Resolute Bay. Photo: Kevin Oliver

Second stage

Our concerns about the ice coverage and speed of its break-up was crystalising into an awareness that it appeared to be a relatively heavy ice year. This created some uncertainty about what lay ahead.

Approaching the North Water, we waited for the pack ice in Melville Bay to dissipate. With some poor weather approaching and plenty of ice offshore we spent almost a week near a landmark called The Devil’s Thumb where Kev led a number of mountaineering shore excursions. These included an attempt to summit The Thumb, from which we turned back due to a lack of specialist rock climbing gear. The sea water was cold and, despite the 24 hour sunlight, in one bay the surface had settled into pancake ice by early morning.

Crucial to our comfort on board was the small stove in the saloon. Our usual type of coal having been unavailable in North America, we’d settled on a ¼-ton of anthracite sourced, delivered and stowed with difficulty. Gentle concern mounted as we found the anthracite reluctant to ignite without constant and fawning attention. Granted it wasn’t Welsh coal, but there was reasonable expectation that it might be flammable. The riddle was finally solved by taking a sack ashore and individually crushing the anthracite rocks into pebbles with the lump hammer. A dull task that involved the frying pan as an anvil.

Sailing the Northwest Passage means spectacular scenery. Photo: Will Stirling

A weather opportunity arose for an attempt to cross over to the beginning of the Northwest Passage. Our route across the North Water to Canada was rather meandering in order to have least exposure to the pack ice. Nevertheless, three days is quite a long time to spend in persistently thick fog with blue sky above the masthead – for those who may doubt, fogbows do exist!

While underway we used the sun to check the compass at local midnight. Ordinarily this would be done at local noon with the sun due south. As we were sailing north and the sun was above the horizon all the time, we used the sun due north at midnight. There was a small amount of maths involved; as we sailed further north, the magnetic variation between the magnetic pole and the geographic pole increased to almost 40° with one chart noting ‘magnetic compass useless in this area’.

Following the retreating pack ice edge west along Lancaster Sound, we took shelter from stronger winds in Erebus and Terror Bay beside Beechey Island, the Franklin Expedition’s winter quarters of 1845. Having climbed up to Franklin’s cairn to gain height we were able to survey the ice conditions to the west and choose a route through to Resolute.

Integrity moving fast in Newfoundland. Photo: Will Stirling

Within six hours of anchoring in Resolute Bay the wind changed and the ice sailed in, surrounding the boat and dragging her towards the shore. Having extricated ourselves from its icy grip we chose an equally unsuitable anchoring spot when, fortunately, a local hunter guided us to a partially sheltered cove where we were able to pole the more threatening ice away from the boat. Options for shelter were limited so we heeded more local advice, moving to a secluded bay nearby from where the Resolute Royal Canadian Mounted Police detachment kindly facilitated the final crew change.

Storm-bound

We remained cornered near Resolute for 12 days, initially by ice and then by a storm. The word is not used lightly: for five days we were confined on board, unable to leave the boat because of the sea state. Luckily we had forewarning and had chosen our anchorage carefully in respect of both wind and ice. With 36 hours of moderate weather between the next low pressure system and the ice having finally been dispersed by the wind, we agreed to take the rough with the smooth and get into Peel Sound.

Shore party staying in touch with the boat in Greenland. Photo: Will Stirling

Transiting Peel Sound is a crucial milestone because it is an ice choke point. The later it opens, the later in the season we would emerge in Alaska and the greater probability of autumn trouble in the Bering Sea. Down Peel Sound, across the St Roch Basin and through Rae Straight led us on to Gjoa Haven, ‘The most perfect little harbour in the world’, which Amundsen found in 1903 and where he overwintered for two years.

Sailing from Gjoa Haven, we negotiated Simpson Straight, the narrowest part of the Northwest Passage and the site of the Franklin Expedition’s last stand in the somberly named Starvation Cove. Darkness had started to set in at night, though both the cold and dark were compensated by the Northern Lights.

Integrity had a good run with the square sail out of Dolphin and Union Straight. This was the final narrow passage between mainland North America and the Arctic Islands, leading into the Beaufort Sea. With boisterous weather building up again, we careered into a lovely bay giving protection from all directions of wind – fortunate as over the subsequent six days a gale blew from the north-west and then south-east.

On a day when we could get ashore by dinghy, we walked seven miles to a river to fish. We didn’t catch any, but it was good to be out in the countryside – a low lying desert of brown gravel as far as the eye can see. With reduced visual inputs you become sensitive to nuance; the changing light on the land could be captivating.

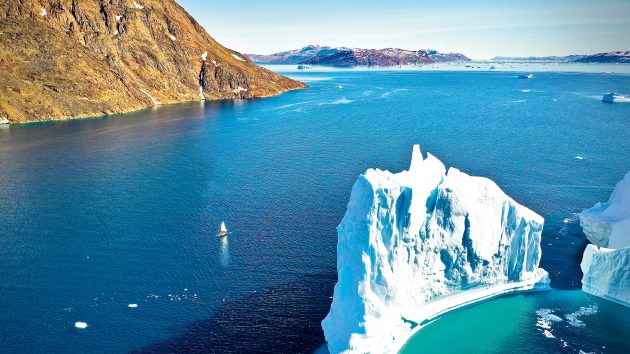

Disko Island in Greenland’s Disko Bay. Photo: Will Stirling

Pressing on

At this stage, due to unseasonably strong weather, we’d covered one-third of the distance of the third leg in two-thirds of the allocated time. Patience is an essential trait of the Arctic traveller; with 1,500 miles to go, we kept busy while waiting for the opportunity to press on.

The gales finally abated to allow us to sail 750 miles to Point Barrow, the north-west point of mainland North America. It was a helter-skelter journey in order to make the most of the reasonable weather, with only two brief stops. One was at Tuktoyaktuk, the northern end of the ice road where we saw the tug and barge trains which service the settlements in the summer, the other at Herschel Island where Inuviak rangers were packing up after the summer. They were most hospitable and their hut very warm.

The Beaufort Sea is shallow and we became used to approaching land in 4m of water. Care is required as the Canadian charts are in feet; the USA charts in fathoms and the digital charts in metres! The compass became more useful as we moved west past the longitude of the magnetic North Pole. The magnetic variation changed to east and reduced to a mere 9°.

The sun never sets during the high latitudes summer. Photo: Hugh Coulson

On leaving Canada we entered United States territorial waters. We attempted to stop at the settlement of Kaktovik for shelter from weather but on approach it was too shallow. It was windy and there was evidence of a sand bar with breaking waves. While we hauled our wind and dealt with the sails two polar bears played in the water nearby. So instead it was fresh water rationing and straight on for Point Barrow: a passage of wind, fog, a Northern Lights display, and never enough sleep!

There was some brave action from the crew at Barrow, where we took on fuel and water. It involved landing on an open beach and twice the dinghy was swamped in the surf. The stakes are a bit higher when the water is 1.5°C.

Our final leg of 550 miles remained across the Chukchi Sea and through the Bering Strait. Onwards we sailed south past Icy Cape, across the Arctic circle, through the gap beside the Diomede Islands (where Russia and the USA are just two miles apart) and into the safety of Nome harbour, the gold panning town where Integrity is overwintering. Destination reached: voyage complete.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.