When we set out to hoist a trysail in 40-plus knots of wind near Cape Horn we soon found out why four reefs in the mainsail is the preferred sailplan of Skip Novak. In this part he looks as storm sails

I have to admit to being highly amused when I hear what pundits have to say about storm jibs and storm trysails. In my IOR racing days (I go back to the days before headfoils!), we often used the No 5 – in effect, a storm jib, hanked onto the headstay by a crew of heavyweights while half-underwater.

Trysails? Well, I used one once on the last leg of the 1981-82 Whitbread Round the World Race. We were in a blow off the Azores and had damaged the mainsail. But we wouldn’t have bothered if we weren’t racing.

So-called storm sails that spend 99.9 per cent of their time stowed below decks gathering mould are all very good in theory. But believe me, they are a nightmare to deploy in practice unless you are so conservative that you are content to fly almost nothing in near-calm conditions before the gale to storm force winds and seas that you anticipate some time in the future. This hypothetical ‘wait and see’ approach can be dispiriting.

We are talking about cruising here which is, by definition, short-handed; often double-handed and sometimes single-handed. To my way of thinking, your storm sails should be rigged and ready to go, deployed early but at the right time, set easily and without fuss or risk.

The trysail dilemma

The dilemma over whether to reef or set a trysail is no dilemma at all once you convince your sailmaker to put a fourth reef in your mainsail. They don’t like it as a rule and will argue on points such as the weight penalty aloft. And for some there are aesthetic considerations.

Remember, though, that we are considering world cruising, not performance cruising, which can quickly become a misnomer in anything above about 25 knots of wind. Yes, a fourth reef is more costly, but it is well worth it.

The only way to convince yourself of this concept is to take the time in a blow offshore and deploy your storm trysail as an exercise, which is what we did to show you in the video that goes with this feature.

Many serious cruisers worth their salt permanently stow their trysail along the boom, loaded onto a secondary track, and even have a secondary main halyard all ready to go. But there is still a lot of work to do – properly securing the mainsail and primary halyard for a start. Starting the manoeuvre by locating the trysail where you thought it was below is more testing.

Hoisting a trysail in storm conditions can be problematic. By that stage you are usually running before the wind and the sail will plaster itself against the rig, creating enormous friction. A slack halyard – it always goes slack at some point during this manoeuvre – can easily swing forward of the spreaders, and all kinds of handling errors can occur, things that are never practised enough. And when it is blowing 40-plus knots, flogging trysail sheets can get dramatic, able to crack open your head.

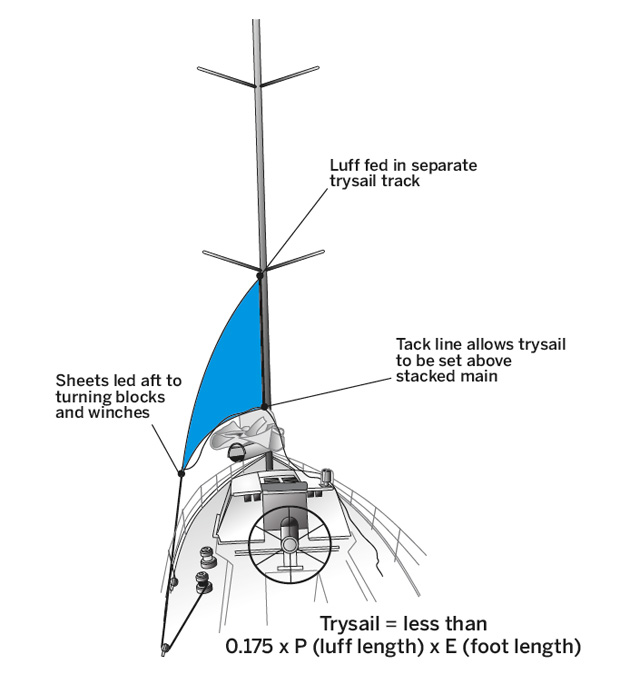

So why not do a manoeuvre that you do all the time instead: taking in a reef? There is no difference between this and taking in the first, second or third reef. In fact, taking in a fourth is even easier as there is not much sail left. What remains will be about trysail size, defined as something less than 0.175 x P (luff length) x E (foot length).

The first, slightly precarious step of getting a trysail up is lowering the main and wrangling it down the luff track

It is a matter of a few minutes to shorten down to storm configuration. The clew height of all the reefs should rise slightly as you shorten down, to be significant for the third and fourth reef. The seas will be big by this stage and a roll with the boom end in the water could end in tears. Admittedly, a trysail would not suffer this risk.

The fact is, unless things become very dire, such as the classic scenario of having to claw off a lee shore, few people would bother to use a trysail once the main has come down from three reefs, which happens often as the third reef usually leaves a massive amount of sail. Sailing under a partially rolled up jib alone is fine if you are content corkscrewing your way off the wind and rolling around underpowered.

If you have to reach, even with the wind at, say, 60-80° apparent in big seas, you will go nowhere.

With a fourth reef and a properly shaped storm jib, you should be able to carry on in well over 40 knots, roughly in the direction you want to go, in balance and in some modicum of comfort.

It must be pointed out that if you did blow the head off the mainsail or suffer any significant damage above the fourth reef, this whole argument becomes moot. Therefore, as the various regulations stipulate, carry a trysail in case and as the name suggests, ‘try’ to learn how to use it.

Storm jibs

There seems to be a plethora of solutions for setting storm jibs. Hanked on to a bare stay or foil is the traditional and simplest solution. This means first dropping a sail and stowing it below – a gymnastic feat in itself.

In any case, few people have anything but roller-furling these days, which presents problems at the outset. I’ve seen various slipover, wrap-around-furled-sail inventions, which can be discarded forthwith (read the forums on it). There are storm sails hoisted on stays, but these are cumbersome to stow and awkward to hoist.

Given that we are talking about sailing in the open ocean where there will be big waves and swell, being on the foredeck manipulating any variation of this gear is a risky business, with stories legion of things (even people) going over the side or tangled up in gear.

Ideally, every cruising boat should have three roller-furling sails up front, a common configuration for single- and double-handers on the round the world IMOCA 60s. One would be a big yankee on the headstay, say 140 per cent for light to moderate winds, which is either rolled up or all the way out and used primarily for reaching.

The second is a working jib on a forestay close behind the headstay of around 90 per cent for mid-range to fresh conditions upwind and reaching. This sail should be cut to furl partially and, again like the yankee, cut high-clewed for good visibility below the foot, but also to avoid having continually to change the lead when rolling in and out.

This combination takes you through most conditions up to the time you fully roll up the jib. Next, simply roll out your third sail, the staysail and, hey presto, you are under storm jib. (For more on this, don’t miss a feature on sail design later in this series.)

Accepting that there is a performance margin in light to moderate air that will be lost in not having a large staysail, it makes sense to make the staysail the true storm jib. This should be a bulletproof sail, cut flat, high-clewed and roughly the same area as a moderate-sized storm jib. This sail should also be able to be rolled up to ‘Oh my God’ conditions – which is basically a clew patch. Because this sail is so small, it takes little time to roll it up and if it is on a self-tacking traveller, so much the better.

By the way, one of the biggest advantages of having readily available storm sails that can be deployed at will is when heaving to – and there’ll be much more on that in the next feature in this series.

Part 4: heaving to

Skip Novak demonstrates this simple and often overlooked technique, a safe and comfortable way for any crew to ride out heavy weather, let a system pass or allow crew to rest up

12-part series in association with Pantaenius