Volvo Ocean Race press conference about Team Vestas Wind shipwreck had no definitive answers to offer

What happened to cause Team Vestas Wind to hit a reef in the Indian Ocean last week and what will happen to the wreck? These are questions that almost everyone following the race has been asking for a week, and which we hoped would be answered this morning at a hastily arranged press conference.

The Volvo Ocean Race press conference about the Team Vestas Wind shipwreck was announced yesterday evening and scheduled for 0730UTC, an early Monday start so difficult, especially in the US, that it smacked just a little of what political spin doctors refer to as ‘burying bad news’.

But it turned out not to be a burial at all, just a light scuffling of soil around the body. There were to be no definitive answers to any of the pressing questions – why, how, what next – and it ended with a vague promise to reveal “honest and open” answers at some unspecified time in the future.

Here is what we do know. During the day of 29 November, the leading yachts passed to the west of the Cargados Carajos Shoal reefs, around 200 miles north-east of Mauritius. On board Abu Dhabi they noted that this was hard to spot. The comment would suggest the crew expected to see this reef and were keeping watch for it.

It was dark when Team Vestas Wind approached, and they were not keeping a watch for it nor, it sounds, were they expecting a reef to be there at all.

At the press conference today Chris Nicholson explained: “Prior to the crash we noticed there would be some sea mounts, and I asked what the wave, current and sea conditions would be. They went from 3000m to 40m. The current was negligible and we decided we would monitor the wave state as we approached; 40m [would be] perfectly safe to cross.”

It was, he added, “a big mistake that we made.” And while he did not elaborate precisely on this mistake, he said: “It was a simple human mistake,” and added that it was “a simple question of zoom.”

There were to be no further details, and no further discussion or mention of Nicholson’s earlier statement that, as skipper, he took ultimate responsibility for the loss. “We have not yet managed to get the computers up and running. We would like do this and hopefully we will be able to,” he said.

Knut Frostad was keen to move on. “You made a serious mistake, but then you didn’t make any more,” he said.

As I speculated last week, most likely Verbraak did not zoom in closely enough along his track. He therefore failed to see that the shoal patches shown at a small scale resolved into large drying reefs when zoomed to a larger scale.

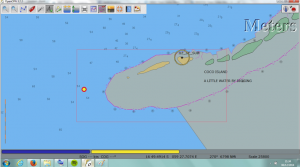

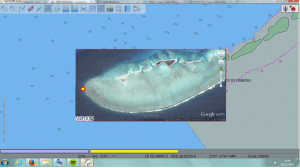

This is a well known electronic charting flaw, an anomaly encountered quite frequently, especially in poorly charted areas and well known to ocean navigators, professional and amateur. The huge difference in appearance of this very reef at different zoom levels on some charts is shown in my earlier blog here.

Another point of interest is that the reef is not in the position charted. Using Google Earth images georeferenced and overlaid on electronic charts, one can calculate that the reef is approximately 0.46 nautical miles from of the charted position. The red dot annotated in these screen grabs of this show that the reef is to the west of its charted position.

Whether that is relevant to Team Vestas’s mistake we don’t yet know. If Verbraak and Nicholson thought the minimum depth in the area they were to cross was 40m, knowing of this chart inaccuracy would have made no difference. But it does beg the question of whether boats ahead which also cut very close, such as Dongfeng, were themselves aware of the extent and real position of the reef. Did they really mean to cut the reef so close? Possibly not.

Another reason we can be reasonably sure Verbraak believed there was no hazard ahead is because he was asleep at the time. In his account on his Facebook page – taken down the same day he posted it but reproduced elsewhere, including our Facebook page – he confesses that before the crash he had put his ‘head down for a rest after a very long day negotiating the tropical storm’.

What navigator would go to sleep when a reef is about to be passed close at night? What skipper would allow that to happen? A navigator and a skipper who both had no inkling of what lay ahead.

Actually, I think you can see that from the on board video. After two huge bangs stop the boat dead in its tracks, one of the crew rushes down to leeward, peers out into the darkness and says: “It’s a ROCK!” in utter amazement. What else could it have been, amid shoals? Yet judging by the tone of voice, the sight was as unexpected and astonishing as an encounter with the Kraken.

So, this was a basic error of navigation and seamanship, a failure to properly walk the course and obtain detailed data about it. Maybe it was also a failure to use a secondary method of navigation, even something as low tech as a depth sounder alarm.

I’m not saying I don’t have enormous sympathy for their plight. As I wrote before, if you sail far enough or long enough, mightn’t you make a few mistakes yourself? Especially under pressure, with your eyes on the weather, and on the race.

What, if any, role did the race organisers play? Did the pre-race briefing point out these hazards? That was one of the questions asked this morning (journalists were instructed to submit their questions in advance on Sunday night; questions were not taken at the telephone conference).

Did any race waypoints take them closer to this area than was sensible? Were there any mitigating factors?

Questioned this morning about the briefing, CEO Knut Frostad surely knew exactly what was being asked but replied obliquely. “First of all, I must say it is the skippers’ and teams’ responsibility to make a passage plan and make their own decisions on where they go,” he pointed out.

This is indubitably true; the sole responsibly of a skipper for the safety of the ship and crew is rightly enshrined in racing rules. But we know that there was a course change shortly before the start of the leg; Wouter Verbraak told us so in his retracted Facebook post. He told us that he thought he ‘would have enough information with me to look at the changes in our route as we went along.’

Were the electronic charts supplied to the crews adequate? Were the organisers themselves aware of the hazards of these reefs, had they taken note of the chart inaccuracies and zoom errors? Could the new course have taken the fleet closer to these shoals than was sensible?

Questions still lie unanswered while, no doubt, discussions play out about how and what insurance will cover, and the costs of removing the wreck, something which can be very, very expensive. This, however, has no financial consequences for sponsors Vestas, group vice president Morten Albæk said this morning, as the boat is owned by the Volvo Ocean Race and leased to the company.

We were just told that removing the wreck “in its current form” or in parts is “not confirmed in detail but we are supporting the work.”

Meanwhile, there are still hints that the crew of Team Vestas might be back in the race if this proves possible. There is no spare boat, contrary to some rumours, but with the race due to continue until June is there the outside possibility of building another yacht and, perhaps, completing the final leg(s)?

Lead times for components, including the pre-preg carbon from which the hull is built, is likely a factor in this. Frostad wouldn’t say for sure whether it could happen, only that it was something they were working on very hard.

And for their part, Vestas said they had every confidence in Chris Nicholson. “It will be Chris as skipper if we are sailing again,” said Albæk. “I trust him completely.”

Frostad finished by promising that “learnings will be published and shared. We want the whole sport to benefit from what we learn.”

“I think it’s very imporant in our culture to be very open and honest,” Chris Nicholson agreed. “In the weeks ahead we can go into much finer detail.”

Let’s hope they do. The Volvo Ocean Race’s audience is more knowledgeable, intelligent and sophisticated than the media output is catering for – or perhaps wishes to – and, unanswered, these fundamental questions won’t go away. How did a crew of professionals come to make such a fundamental and catastrophic mistake, or series of mistakes?

Earlier story: ‘How could a yacht bristling with technology hit a known reef?’ here