STRUCTURAL FAILURE

The report sets out that, ‘In the absence of survivors and material evidence, the causes of the accident remain a matter of some speculation.’ Yet the evidence that has been compiled does draw some significant conclusions.

‘Cheeki Rafiki capsized and inverted following a detachment of its keel,’ it reads. ‘In the absence of any apparent damage to the hull or rudder other than that directly associated with keel detachment, it is unlikely that the vessel had struck a submerged object. Instead, a combined effect of previous groundings and subsequent repairs to its keel and matrix had possibly weakened the vessel’s structure where the keel was attached to the hull. It is also possible that one or more keel bolts had deteriorated. A consequential loss of strength may have allowed movement of the keel, which would have been exacerbated by increased transverse loading through sailing in worsening sea conditions.’

So while a weakened structure is believed to be the primary cause for the failure, the route that Cheeki Rafiki took and the weather that the crew ran into also played a part.

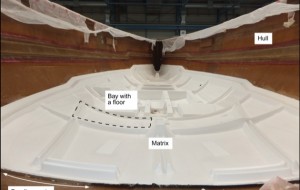

The structural failure of the hull to keel attachment is an area that the report focuses on in detail, starting with the design and manufacture of the First 40.7, in particular the internal liner/matrix and the potential for this to become detached from the hull.

During the course of the investigation, the MAIB received much anecdotal evidence regarding matrix detachments on Beneteau First 40.7 yachts. Areas notable for detachment were in the forward sections of the matrix, commonly attributed to the vessel slamming, and the area around and aft of where the keel is attached to the hull, commonly attributed to the vessel grounding.

MAIB inspectors visited four Beneteau First 40.7 yachts that had all suffered detachments of their matrix in bays around the aft end of the keel as a result of grounding. Additionally, two of these vessels had suffered, or were showing signs of, matrix detachment in the forward section.

One further Beneteau First 40.7 yacht was visited, which showed signs of matrix detachment in the forward and aft sections.

In the case of Cheeki Rafiki, the MAIB report established that the boat had suffered several groundings between 2007 and 2011, some of which had led to various inspections and repairs.

CODING & INSPECTIONS

Because the boat was operated commercially she needed to comply with the SCV (Small Commercial Vessel) code. To do this requires regular inspections, a duty not required for privately operated boats and yet a process that had provided a valuable safety check for Cheeki Rafiki.

Cheeki Rafiki had obtained Category 2 coding in 2011 (allowing it to be operated up to 60 miles from a safe haven) and had been inspected out of the water where a YDSA (Yacht Design and Surveyor’s Association) surveyor had discovered a detachment of Cheeki Rafiki’s matrix in the forward section. A repair was made.

The boat was then due for its next inspection by 18 March 2014 but at this stage the yacht was in the Caribbean.

Stormforce Coaching asked YDSA to grant an extension to allow the survey to be completed when the vessel was back in the UK. YDSA passed the request to the MCA, who confirmed that no extension was permitted under the SCV Code. Owing to the cost of completing the survey while in the Caribbean Sea, it was not carried out and Cheeki Rafiki’s Category 2 coding expired.

In correspondence between the MCA and the YDSA concern was expressed at how a yacht run commercially across the Atlantic could operate on a Cat 2 certificate. Stormforce Coaching’s position was that because she had raced across the Atlantic in the ARC she was under ISAF regulations and not those of the MCA code and therefore didn’t need a Category 0 coding for ocean crossings. Looking at the wording alone illustrates why the company took this view.

Section 28 of the SCV Code states that; ‘A coded vessel chartered or operated commercially, for the purpose of racing need not comply with the provisions of the Code whilst racing, or whilst in passage directly to or from a race.’

The MCA didn’t agree stating that; ‘Paying passengers are only

one element of the definition. If the voyage is a relocation voyage for commercial purposes, the vessel is almost certainly not being used as a pleasure vessel.’

It is understood that the intention of this part of the code was to allow boats to get to and from the start/finish area rather than to make extended passages. At the very least the issue has highlighted concerns as to the coding requirements and definitions of racing and commercial operations.

“During the investigation it became clear that opinions were divided as to whether or not Cheeki Rafiki’s return passage across the Atlantic Ocean was a commercial activity,” said MAIB Chief Inspector Steve Clinch. “I have therefore made a recommendation to the Maritime and Coastguard Agency to improve the guidance on when small vessels are, or are not required to have commercial certification. This should help resolve what has, for too long, been a grey area.”

While the ruling itself would not necessarily affect the potential for such an incident, in this case the coincidence over the timing of the inspection and that the boat’s structure was not formally inspected before she set out on the trip to the UK, appears to have played a part in the tragic outcome.

Next page: How groundings led to the failure and why we should all take note