The Dream of the West Indies is a tale of four schoolboys on an adventurous transatlantic crossing that's enough to turn any parent’s hair grey. Tom Cunliffe introduces this extract

In the summer of 1983, a group of very young Norwegians set out on a round trip to the Caribbean in Jeanette VI, a 35ft Vindø yacht they chartered from a sympathetic ‘grown-up’. Morten Stødle and his peers were schoolboys not yet at university, but came from sailing families and all had the same dream.

Almost 40 years later, two of them, Stødle and Hauk Larsen Wahl, have gathered the diaries they wrote and given a ‘warts and all’ account of the trip. Their book, The Dream of the West Indies, is youthful, fresh and positive.

The lads left home with patched Levi jeans, knitted jumpers, three SLR cameras, two empty diaries and the New Testament. Although they’d all been sailing most of their lives, the big seas were a ‘learn-as-you-go’ experience. We join them first in the Azores, sharing their delight at finding themselves in a real seafaring community, then follow them up to the English Channel, through one wretched weather system to the next, until they’re hit by a storm that comes close to ending the adventure.

Extract from The Dream of the West Indies

Extract from The Dream of the West Indies

We have mostly fine weather for the 1950 miles from Bermuda until we see land in Faial, the westernmost island in the Azores, at 0900 on 22 April 1984. We dock in the guest harbour at the port of Horta, and look forward to a cold beer at Café Sport, and a warm shower.

Café Sport, also known as Peter’s Bar, has been visited by many famous adventurers and globetrotters throughout its long history. As has become a tradition, we hand over a Norwegian flag to the charming owner Peter, which he hangs up on the wall straight away; we hope it will decorate the bar for a long time after we leave.

Joshua Slocum, who arrived at Faial in July 1895 from Boston with his 37ft sloop Spray, had an eventful stay on the island, as described in the book Sailing Alone Around the World. ‘I remained four days at Fayal, which was two days more than I had intended to stay. It was the kindness of the islanders and their touching simplicity which detained me’.

It was great fun to meet other sailors in Horta, and we had a few cheerful evenings in the cockpit and the cabin with Germans, Danes, French and English.

Erling remembers: “I recall a detail from our arrival in Horta: the engine did not work. So, we came sailing into port in a strong breeze and spotted a place to dock. We reached past the quayside, turned the helm, went straight upwind and drifted perfectly into the dock, moored and took down the sails. The number of times we sailed out of ports, and especially into ports, without an engine, is something I think back on with great pleasure.”

Passage to England

We cast off at 0130 after a fitting farewell party with the sailors we’d had the pleasure of meeting in Horta over the last few days. We now face a strong breeze from the north-east, which means we must tack upwind and take a pounding from the waves while making slow progress towards our next goal, which is England.

Arne remembers: The sailing trip from the Azores to England was long (15 days) and cold as we tacked against the wind with waves coming towards us. It takes approximately 20 minutes from the time you see the light of a cargo ship until you might collide. To safeguard against this, it is important to scout around regularly. After seven days of sailing, I fell asleep on my night shift and woke up after roughly 20 minutes with horror when I saw a Soviet supertanker only a few hundred metres away from our boat.

The ship had a giant Soviet flag with a hammer and sickle waving in the wind. I shouted down to Hauk and Erling that they had to get on deck so that we could tack immediately. It was an intense experience to see a huge ship so close after not seeing anything out there for seven days. This was the last time I fell asleep on my watch.

Morten Stødle, Hauk Larsen Wahl, Erling Kagge and Arne Saugstad

On Monday 30 April the barometer begins to drop rapidly. On the night of Tuesday 1 May we experience a strong gale from the north, and the waves build up. We all put on our survival suits and clip ourselves to the boat when we are on deck or in the cockpit. We take several reefs in the mainsail and replace the genoa with a storm jib.

Over the course of the day, the wind increases to a strong gale, with the anemometer showing 45-50 knots. By now, we have taken down the mainsail completely and sail with only a storm jib, with a drift anchor trailing the boat to reduce speed when we surf down the waves, which are now 8-10m high, with streaks of foam and sea spray that stings the eyes. I silently pray to God that we will get through the next 24 hours without the mast breaking or the boat sinking and feel the claw of anxiety in my chest.

I think of my great-grandfather Ole Andresen, who was the chief engineer on the Wilhelmsen cargo ship named Tordis. He was back home in Norway for short periods only every year and a half, during which his wife, Anna, got pregnant, eventually raising five children more or less on her own. In 1917 at the age of 54, halfway between Brisbane and Buenos Aires, he suffered a massive heart attack and died. He was buried at sea.

It becomes very difficult to steer the boat with such limited sail area in use, and Jeanette gyrates back and forth. A large wave comes from behind, lifts the boat up and sends her downhill in a wild surf. We hit the oncoming wave at probably 10 knots, which tosses the boat to one side like a toy, and we experience our first knockdown, the mast slaps into the sea, the cockpit fills up with seawater in a second, and we hold on as the cold Atlantic sea seeps through the openings in the doorway down to the cabin. Slowly but surely, the boat straightens up, and we desperately try to gain steering speed forward. All men are in action, one as helmsman, one with a 10lt bucket and one operating the manual bilge pump, while seawater mixed with oil from the bilge is sloshing around the cabin.

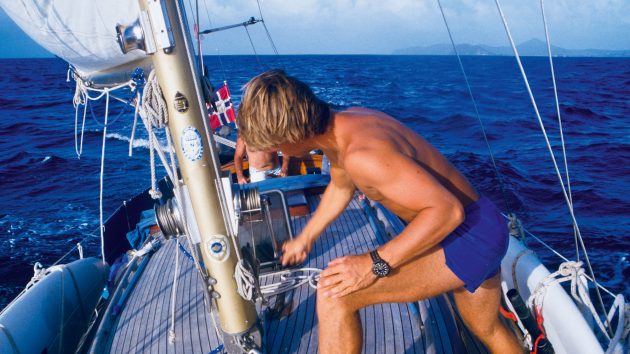

Morten kitted up and clipped on for safety in turbulent waters – but still having fun. Photo: Arne Saugstad

Everything is soaking wet and chaotic. We start the engine to get more steering speed and charge the batteries, but this causes a rope trailing the boat to get stuck in the propeller and we are now in deep trouble.

We continue the struggle to keep a fairly steady heading, but lose control several times, and Jeanette is again thrown to her side with the mast parallel to the sea. Incredibly, we avoid the nightmare of dismasting. The sea off the Bay of Biscay is furious today and the pleasant trade winds we enjoyed westbound towards the Caribbean seem very distant.

Article continues below…

Great seamanship on the Southern Ocean

The experts comment on Dee Caffari's amazing feat through the Southern Ocean 23/3/06

Great Seamanship: sailing through desert storms in the Suez Canal

Sailing Suleika by Dennis Krebs is a long sea-mile from a typical description of an extended cruise. Dennis met up…

Freak wave

Then we are suddenly hit by something that can be categorised as a freak wave. A huge wave towering behind us breaks, delivering a powerful shock that causes Jeanette to shake while at the same time hits the foredeck with great force. The solid mahogany hatch covering the opening down to the forward bunk is torn from its hinges, sent flying like a frisbee through the air and landing in the rough sea a few metres on the starboard side.

Luckily, we have daylight, so we can see the hatch floating in the sea. We desperately try to get hold of it, because large quantities of seawater are now being dumped into the forward bunk with every wave that hits us. After a few seconds of discussion, I tie a line to my safety harness, jump overboard, swim a few metres, and grab hold of the hatch. The guys haul me back to the boat, and after a few attempts in the rough sea I manage to climb up the swim ladder on the stern with the hatch intact.

Arne and Morton get to grips with the sextant. Erling and Hauk came from Norwegian sailing families, but huge Atlantic seas were a learning experience for all. Photo: Hauk Larsen Wahl

During the next few minutes, we manage to nail the hatch into the opening in the deck with some seriously large nails, which stops more seawater from filling up the inside of the boat. The cabin now looks like an indoor swimming pool. Everything floats around, and we use all our strength to manually operate the bilge pump and carry bucket upon bucket of water out of the cabin. In the end, we manage to empty seawater out of the cabin to a large extent, and we concentrate on keeping enough speed to steer the boat and avoid any more knockdowns.

The wind gradually dies down in the subsequent days after the storm and the swells subside, so we sail mostly close hauled to the north-east with winds from the north and north-west, noticing that it is gradually getting cooler in the sea and air. On 4 May we discover that the stainless steel base that secures the forestay to the deck by the bow appears damaged, so we take down the genoa for safety’s sake and take a closer look. We then make a somewhat provisional attempt to strengthen the base, and cross our fingers it will hold.

On 6 May the wind has turned to the north-east, so we are forced to tack westward to avoid getting too far into the Bay of Biscay.

For the next two to three days we take several tacks to get further north-west before we reach the entrance to the English Channel and our next destination – the town of Lymington, north of the Isle of Wight.

My mother told me when we got home from the trip that she’d had a nightmare one night in early May, in which I was about to drown at sea. It later transpired that she had that nightmare during the same day that we were fighting to keep Jeanette afloat in the storm off Biscay with no way to communicate with our family at home. Telepathy in action.

Tankers and cargo ships could be a threat – but also a godsend. Photo: Hauk Larsen Wahl

Erling remembers: I recall the sails were so blown out and repaired so many times that towards the end of the trip we could sail no closer than about 40° to the apparent wind after a wave ripped through the mainsail in the storm north of Azores.

Because the toilet had long been clogged, we had to do our business over the railing, and when the wind was at its fiercest we didn’t dare and used the galley instead. The cooking stove didn’t work either, so we ate cold corned beef from a can, crispbread soaked in saltwater and uncooked potatoes.

When the boat was filled with seawater during the storm, and the electric bilge pump stopped working, we realised that scared boys with buckets make the best pump in the world.

Fresh rations

The logbook reads: 9 May. Wind: ENE. Weather/Temp: Sunny/12°C. Barometer: 1031mb

Notes: We move the forestay from the broken mount to the one that currently holds.

One day when we are getting closer to the English Channel we spot a large oil tanker which, based on our bearing, seems like it will pass relatively close. We call them up on the VHF and ask politely if they have any food to share with us as our provisions were starting to run very low, and we were pretty tired of a diet of corned beef, potatoes and crackers.

As the tanker with the name El Gaucho passes at a distance of less than 100m, they dump overboard a large 55-gallon oil drum, which we manage to hoist onto the deck. To our great delight, the drum contains a wonderful selection of canned sausages, sardines, milk and salami. Delightful!

The closer we get to the English Channel, the more ship traffic we observe, and later that day we get to convey a message to the family in Norway via a German ship.

The wind turns to the north-west on 10 May, giving us a pleasant broad reach as we pass south of Lands End.

The day after we get a headwind again, but we manage to reach Brixham after 14 days of tough sailing from the Azores. Our stomachs scream for fresh food and cold beer.

Buy The Dream of the West Indies from Amazon

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.