It was the dream of a lifetime for James Ashwell to sail to the remote islands of Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea

For a month, the boys had been hidden in the mountains with their uncles. They had their noses pierced with bamboo and stayed in the ceremonial hut for three nights, while their mothers and aunties conducted a singing vigil. They started the process as boys, but now it was time for them to be released and presented as men.

Their fathers took great care to dress their sons in their most treasured family possessions. They were adorned with huge, century-old hornbill beaks. Priceless pearl shell necklaces, collected from the coastal tribes over centuries, were wrapped around their necks. Necklaces made of parrot feathers completed the look, together with head dresses from possum fur topped with the incredibly rare feathers of the Bird of Paradise.

Finally it was time. The young men were released from the hut and led around by their fathers and mothers with the entire village out to watch. The procession was one of the most dramatic scenes I will ever witness.

Start of adventure

Simbai, in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, is the most remote and inaccessible place I have ever been to. Planning to get here has taken years. I’ve been somewhat obsessed with Papua New Guinea (or PNG) since I was 12 and read a feature in the National Geographic. Ever since then I’ve been desperate to visit. PNG is one of the three key places that gave me the motivation to try to sail around the world.

In the UK I lived with my three best friends and every year we went sailing together. One summer, I said: “Why don’t we do this for a year?” They agreed that if I got a boat, they’d join me. A year and a half later I saw Uhuru, a brokerage Oyster 62, for sale and bought her.

We all quit our jobs. I was running a business and told the shareholders we were off; one of my friends is a doctor, the other is in the film industry. We’d each lost our parents when we were young and knew all too well the fragility of life and the importance of living for the present.

The incredibly remote Tanga Islands, New Ireland, PNG. Photo: James Ashwell

Although we’d sailed together on a lot of charters we had never even crossed the Channel when we set off round the world. We took guidance from an experienced solo sailor for the first few months, who taught us everything we needed to be safe and competent cruisers.

After crossing the Atlantic we spent a year in the Caribbean, then decided to go to the South Pacific via Easter Island and Pitcairn. It was fantastic – the places that other people don’t want to go are the most amazing.

We got as far as New Zealand when Covid struck in 2020, and I got stranded for almost two years, unable to leave because the weather window in April for returning to the Pacific didn’t align with lockdowns. So I decided to completely refit Uhuru. I took apart floors and ceilings, removed every deck fitting, ripped her apart and rebuilt her.

I met my partner, Jin, and it became both our full-time jobs during the strict New Zealand lockdowns.

Departing from New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf, bound for New Caledonia in perfect condition. Photo: James Ashwell

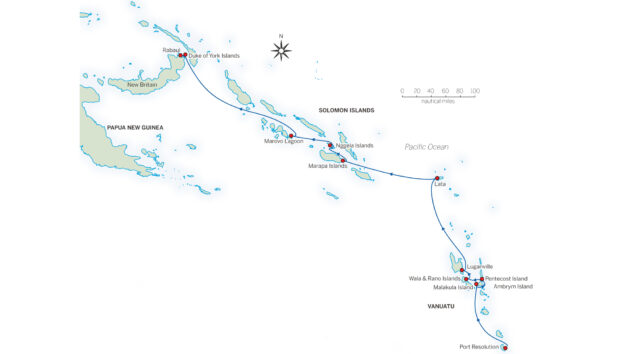

In June 2023 we left New Zealand with a crew of five: me, Jin and three friends we’d met in New Zealand. We progressed from New Caledonia to Vanuatu and by the time we’d sailed onwards to the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea, it was just me and Jin, and our friends Dan and Gareth.

A sacred dance

We had a turbulent crossing from New Caledonia to the island of Tanna in Vanuatu. Our first stop in Vanuatu was the anchorage of Port Resolution, where we cleared in. The bay was sheltered and it felt like a garden of Eden.

Tanna is famous for its active volcano, Mt Yasur. The journey from Port Resolution, crammed into the back of a truck, was memorable in itself. I’ve had only a handful of experiences that are truly breathtaking, but this was definitely one. Nothing had really prepared us for the scene that greeted us at the crater rim.

Gazing into the volcanic abyss of Mt Yasur on Vanuatu’s Tanna Island. Photo: James Ashwell

I can only describe it as peering into hell, with a steep cliff of black earth leading to a deep cauldron of boiling, glowing magma.

When the first explosion went off, so loud that you could feel your body vibrate, the magma shot high into the air and then fell back to earth in what appeared to be slow motion. I was mesmerised.

From here we sailed to Ranon on Ambrym Island, and then to Pentecost Island. In Vanuatu it is believed that the more volcanic an island the more potent is the black magic, and there are few islands more volcanic than the black sand, double crater island of Ambrym.

Sharing kava with locals in Lamen Bay, Epi, Vanuatu. Photo: James Ashwell

The islanders here practise a dance called the Rom dance, a sacred event that is believed to improve the harvest. The ritual stretches back centuries and tells the timeless tale of good versus evil. The locals dress to represent evil spirits, adorned in a thick cloak of dried banana leaves and a conical, brightly painted banana-fibre mask. As the dance begins, story, myth, heritage, and belief entwine with the supernatural in an unfolding rich in symbolism.

Christmas spectacle

I was as excited as a child on Christmas Day when we arrived in the south of Pentecost Island to see the land diving, or Nanggol, probably the most famous custom of Vanuatu and a big part of the reason we chose to sail here. It was certainly an incredible experience to witness.

In mid-July we pressed on to Rano Island, Malakula. We’d heard that local traditions were still thriving on the two stunning islets of Wala and Rano on the north-east of Malakula and so we sailed there to find out. The islet of Rano is as picture perfect as it is possible to get and we dropped anchor on a 10m-deep shelf of pure white sand and gin-clear waters.

Tribesman at PNG’s Goroka Show. Photo: James Ashwell

The Vanuatu islands first had contact with Europeans in 1606, but Malakula was isolated and little visited by Europeans until well into the 20th century. As a result, the island’s indigenous traditions were better preserved there than elsewhere in Vanuatu.

Malakula is as wild as it gets. It is one of the South Pacific islands famed for its history of cannibalism. Sparsely populated with only 23,000 people, the jungle is thick and the land mountainous, which has resulted in 30 languages being spoken in an island the size of West Yorkshire.

It meant local villagers rarely explored the world further than a few miles from their homes. They got along badly with neighbouring villages and communication and trade were limited.

Dramatic arrival at Rabual, New Britain, PNG. Photo: James Ashwell

There were regular wars between tribes. After a battle a couple of captured men would be taken to a site specifically designated for the purpose, then killed and parts of the upper torso eaten. We found a local guide who took us on a trek to one of the cannibal sites deep within the jungle.

The captured men would be taken to an upright stone where they were slaughtered, butchered then cooked. We could clearly see the place where they discarded the bones.

By early August, with the season advancing, it was time for Uhuru to head north and make the 300-mile passage from Luganville to the Solomon Islands. We cleared in at Lata, having contacted customs and immigration in advance. Shortly after we lowered our quarantine flag a lovely lady whose house overlooks the small bay came over to welcome us with a beautiful bouquet of flowers.

Sunset walk with the local kids at Port Resolution, Tanna, Vanuatu. Photo: James Ashwell

We felt it was a good omen for what was to come. Over the next few days we spent a lot of time with Hilda. We toured her beautiful garden filled with orchids. She cooked a traditional meal for us and introduced us to her children.

Heading north we decided to break the journey with a stop in the Marapa Islands. The anchorage I picked out from satellite images turned out to be one of the most beautiful we were lucky enough to enjoy. The tiny island on Paipai reef is everything you’d hope a tropical island to be and we never tired of the stunning view of white sand and palm trees.

Unexpected dance by three local tribes around our camp in Simbai. Photo: James Ashwell

On arrival we followed the process we’d set for ourselves and first asked permission of the locals who own the island and offered gifts. However, it wasn’t long until a dugout canoe with a very angry man arrived asking why we hadn’t asked permission. After a good hour of talking he understood that we’d been fooled earlier by a local from a different village and his anger turned to friendliness. We visited his family, gave some gifts and soon felt comfortable and safe.

Navigation challenges

If you look up the Nggela Islands on Google Earth you will see a tiny sliver of a channel between two huge islands that just begs to be sailed through. The only problem is there’s no data available on any charts that indicate the depth, so it was impossible to know if Uhuru, with a draught of 2.5m, would be able to make it through.

We decided that it looked like an adventure we couldn’t ignore and would be worth a go. So at 0500, before sunrise, we raised anchor and headed for the channel.

We slowed to 3 knots and gingerly entered the passage.

Trading with locals at Nissan Island, Bougainville. Photo: James Ashwell

As the depth reduced from 25m to 5m I started sweating. However, it was well worth the worries as we passed just a few metres away from remote stilt villages and beautiful jungle. We managed to capture depth data the whole way along the passage and passed it on to Navionics so vessels that come in future will know exactly how deep it is.

Friendliest of welcomes

From here we sailed to Roderick Island. On our arrival a man named John came over in a dugout canoe and asked us if we wanted to come over for some drinks. As soon as we arrived at the beach his whole family welcomed us, fully dressed up in their traditional attire. They were singing and chanting as we got off the dinghy.

Only when we walked up from the beach, did the full extent of his efforts hit us. He’d decked out his whole beachfront as if for an extravagant wedding. We entered by passing through a palm entrance arch, each of the palm tips decorated with hibiscus flowers. He presented us with three necklaces each, astonishingly, made from hundreds of orchids. John had made a hand wash bowl out of a giant clam.

Diving straight off Uhuru in Kavieng, New Ireland, PNG. Photo: James Ashwell

After washing our hands, his daughters presented us with cold coconut juice and a leaf plate of food extravagantly decorated with colourful hibiscus flowers.

Following a meal and conversation, we were led by a group of dancing children through a passageway of flowers to the fire. Here, we gathered around, and everybody danced and laughed. The most incredible thing is that John did not do any of this for money and asked for nothing.

He only did it because we’d written to him in advance to ask his permission to anchor on his land, and he wanted to show his welcome. To show our thanks we scuba dived on his mooring lines to check their condition and bought him a load of building supplies to help him refurbish his property.

We could have happily spent several months here. Sadly, the window for heading over the top of Papua New Guinea closes in late October when the winds and current switch direction making the passage almost impossible.

Stern line to a palm tree in a wonderful Duke of York Islands anchorage. Photo: James Ashwell

We made a last stop at the pristine Marovo Lagoon, New Georgia, an incredibly wild place with waters teeming with life and jungle spilling down to the shore. It was a shame to have to rush through the Solomon Islands; we could have spent much longer there.

Beautiful but dangerous

We’d planned to clear into Rabaul, the capital of New Britain, Papua New Guinea, but I had an uncomfortable feeling as soon as we arrived – it was industrial and had a bad energy. So after formalities we headed to a safe anchorage at the nearby Duke of York Islands, where we left Uhuru to venture inland to Papua New Guinea’s mountainous interior. This is not an easy journey. We’d been warned that travelling anywhere in this country is challenging, but we were not prepared for the reality.

Our first experience of tribal culture was at the Goroka Show, one of the largest tribal gatherings in the world.

The show was originally an attempt by missionaries in the 1950s to curb tribal fighting by bringing their different cultures together to showcase each of their distinctive and colourful rituals. Today over 100 tribes gather to perform their songs, dance and show their traditional dress.

Interacting with the tribes at the Goroka Show in PNG. Photo: James Ashwell

At around 2.30pm, way after the time it was suggested we leave, we noticed the mood change. As we walked back to the ‘tourist’ area, we heard gunshots. We started to jog and then realised everyone else was starting to run. It turned into a stampede and the barbed wire fences protecting the package tourists got trampled down.

We ran into the nearby university accommodation and locked ourselves into a bathroom until it felt safe to leave.

From Goroka, we hitched a ride on the missionary plane to Simbai. The views along the way were incredible – dense jungle, misty mountains and villages with not a sign of outside influence.

When we landed in Simbai there was a small gathering of locals keen to see who’d arrived. We didn’t know it yet, but this was to become the most moving and inspirational human interaction of my life.

Exploring the south of Bougainville’s Green Island with local kids. Photo: James Ashwell

After settling down into a traditional hut, high on the mountain side above the village of Simbai, we lit a fire next to our sleeping bags and drifted to sleep. At around 1am we awoke to the distant sound of women’s singing. Eager to not miss out on the festival we got dressed, grabbed our head torches and walked towards the sounds.

Arriving at the ceremonial house we were the only foreigners there and the locals were keen to explain their customs to us. The festival marks the ascent of their chosen boys into manhood. To explain, the village elder invited us into the initiation hut where he showed us the boys recovering from having spears pushed through their noses.

At dawn, the sun rose spectacularly to reveal a clear, blue sky. The valley below was filled by a thick fog. Villagers in traditional dress walked by carrying bows and arrows.

These memories of a rare and genuine tribal celebration in a remote mountainous corner of Papua New Guinea were a privilege I’ll treasure as long as I live. I wonder if my kids’ generation will still be able to witness such an event?

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.