British explorer David Cowper has become the first to transit the Hecla and Fury straits since the route was discovered in 1822. Adrian Morgan reports on one of the most respected marine explorers of all time.

British sailor and explorer David Cowper has successfully transited one of the most difficult routes of the North West Passage, the Hecla and Fury Straits. On 27 August, accompanied by his son, Fred, Cowper became the first to navigate through this passage since William Parry discovered it in 1822 with the ships HMS Hecla and HMS Fury.

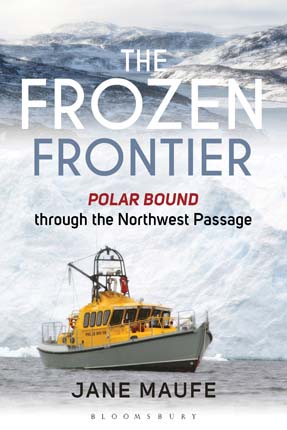

He departed from Maryport in Cumbria at the end of July in his strengthened and specially designed 48ft aluminium motorboat Polar Bound, navigating singlehanded to Greenland. Then, joined by his son, he continued beyond the Arctic Circle, and south of Baffin and Victoria Islands on a route considered by some to be the world’s most difficult.

Conditions were ferocious at times, with strong tidal rips, seas of 7m and more and winds gusting over 60 knots. In Hudson Strait they encountered several miles of ‘swirlers’, which he noted was ‘like being in an 18ft sea that couldn’t find its way out of a washing machine; we were trapped in the cabin being washed around with green water flying over Polar Bound.’

The boat was nearly pitchpoled and father and son were bruised from being thrown around. They lay ahull for several hours until the tide turned. David Cowper noted: ‘conditions were atrocious’.

“Nature is all powerful. Not to be held in contempt”

Polar Bound was designed by Dennis Davidson of Murray Cormack Associates and built by New Century Marine in one of the former minesweeper sheds at the old McGruers yard in Rosneath that Cowper owns. She is shaped like an egg – Cowper would rather describe her as ‘spoon-shaped’ – albeit an egg designed not to crack even under the pressure of 65 tonnes of ice.

The skin is 15mm aluminium, rising to 20mm at the shoulders and close framed, the stringers continuously welded, rather than tacked, every inch ultrasound-tested. “Nature is all powerful,” says Cowper. “Not to be held in contempt. She’s looked after me well in three circumnavigations.”

David Scott Cowper, the 38 year – old lone sailor from Newcastle beats Chichester’s record aboard 41ft Huisman sloop Ocean Bound. Pic: Alamy

Well known in the 1970s for his sailing exploits, Cowper undertook two circumnavigations in the Huisman-built 41ft sloop Ocean Bound. In 1979 he broke Francis Chichester’s record by a day, and two years later, sailing the ‘wrong’ way, beat Chay Blyth’s record (in the much larger British Steel) by 72 days. Before that he raced his 30ft Wanderer sloop Airedale in the 1974 Observer Round Britain and was an OSTAR entrant in 1976.

Fact: In 1982 Cowper became the fastest person to sail single-handed round the world in both directions

Cowper’s move from sail to power in 1984 was logical: whereas ice is ubiquitous in the polar regions, wind is often absent. A ‘shakedown’ cruise round the world in the 42ft cold-moulded former lifeboat Mabel E Holland made Cowper the first person to circumnavigate solo via the Panama Canal in a motor boat.

In July 1986 he left for the Arctic at the start of a solo voyage that was to last four years: via the North West Passage, during which Mabel E Holland survived a sinking while overwintering at Fort Ross, thence round the world for a second time to arrive back in Newcastle in September 1990.

Does he intend to go back to sail one day? “I might take up golf when I’m 90,” he says. “But my passion is still sailing boats. When I’m in port I go round looking at details. It intrigues me. One day I would like to design a perfect sailing boat. The ideal size would be 46ft. Most boats these days are far too sophisticated. I threw out the hot water system and desalinator. It all goes wrong.”

Meticulous planning

Prior to this summer’s Hecla and Fury voyage, Polar Bound underwent a two-year refit, having successfully returned from the Arctic after Cowper’s fifth – and most audacious – transit of the North West Passage, via the McClure Strait, the most northerly of the seven routes, one of a number of ‘firsts’ achieved by this most modest of seafarers.

Yachting World report from 2012: David Cowper through McClure Strait

Polar Bound’s refit has been forensic. Cowper leads me down the double-dogged forehatch in the forepeak, where shelves of plastic boxes contain everything he will need on a voyage he says will last one, maybe two – who knows – three years? A vicious-looking old wooden-handled RNLI boathook rests against the hull, a relic from the Watson, used for cutting weed off clogged propellers.

Watertight bulkheads separate this from the engine room and bow compartment. The space is immensely strong. This is the second line of defence, the first being a stem, already super-strong, further protected by a sharp, hefty strip of aluminium.

Every seacock and valve is accessible; every one has been dismantled and greased. Cowper has a tool for everything. A Dickinson Bering stove in the saloon, insulated with one tonne of rock wool, has been nickel-plated. “I hate rust,” he says with a passion you might express about mice in the rafters.

Cowper was the first person to transit the McClure Strait, the most northerly navigable route of the Canadian North West Passage.

Meticulous planning underpins everything he does. The 18mm toughened glass wheelhouse windows, as fitted to RNLI lifeboats, and 10mm polycarbonate side windows – Polar Bound is self-righting – have been removed and rebedded; the wipers – “very poor, all mixtures of metals” – dismantled and rebuilt.

Meticulous, but frugal. The man himself is spare. The shower looks unused. “Clean people don’t need a shower,” he says, apparently quite seriously, although I can’t be sure.

Yet expense is not spared on the essentials. The air-damped wheelhouse seat was bought cheaply off a police boat. Polar Bound carries £20,000 worth of diesel, much of which he intends to buy in Greenland “where it’s subsidised”.

At the heart of every Polar Bound voyage is a piece of reciprocating machinery that must match its owner in strength, resilience and reliability: the Gardner eight-cylinder LXB 150hp diesel engine that for thousands of sea miles in polar, Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean and Antarctic waters has turned a four-bladed 3ft bronze propeller (one of two; he carries a spare). At a steady 900 revolutions per minute, hour after hour, day after day, it is akin to a human heart, and just as vital.

Perfectionist tendencies

A fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, with a business to run back in Newcastle, Cowper is still at work, as frequent calls to his mobile attest. In 1986, returning from the Arctic, where Mabel E Holland had been left after failing to force the Bellot Strait, he worked his passage home on the Esso Imperial “peeling potatoes”.

His first yacht, the 30ft Laurent Giles Wanderer Airedale, he bought as a student for £5,000. “All my money at the time,” he recalls.

“I’ve been fortunate, always having had new yachts,” Cowper says, a luxury that does not come cheap given he has eschewed, or rather failed to attract, significant sponsorship over the years. “I gave up trying to be a global superstar years ago.”

Besides, sponsorship would bring with it obligations: to talk, interview, lecture, endorse, meet people. Not that he shows the slightest unease or reticence, let alone irritation, at answering questions and is comfortable in front of a camera. You get the impression that he would relish a little more recognition, but the relative lack of it does not bother him unduly. Named Yachtsman of the Year in 1990, he has a devoted following among those who matter, which is all that matters to him.

Those records cannot lie: his Ocean Bound feats aside, he will always be first to circumnavigate the world non-stop in a motor boat and to transit the North West Passage alone, and more besides. Between 2009 and 2011 he completed the voyage westward through the passage, down the coast of South America to the Antarctic, South Georgia – “My favourite place; special, unmolested wildlife” – via Cape Town to Australia, Fiji, Hawaii and doubling back again east, via the Passage. It was his sixth solo circumnavigation, and another first.

Jane Maufe – his somewhat younger, able crew and companion – who was aboard for his 2012 transit via the McClure Strait, describes him as “a perfectionist” and “old school, in the nicest possible way”.

“He has strong opinions about lots of things,” she says. “He’s also very knowledgeable.” Of the exploitation of the Arctic by charter boats and cruise ships he is scathing: “People want instant satisfaction. Accidents waiting to happen. It’s not a place to fool around in or take for granted. It may be a little easier than 20 years ago, with global warming, but conditions change in one season. There’ll be Beneteaus cracking like matchsticks.”

Of keels falling off or foiling yachts doing 30 knots with one person aboard, glued to tablets: “Highly dangerous.” His chart table is full Admiralty-sized and watched over by two St Christopher medallions. Is he superstitious? “Well, I would not want to sail on Friday 13th.”

David Cowper with his companion and co-adventurer Jane Maufre

So why is he not better known? It could be down to his age, lack of vanity, or quite simply the fact that most people see the world as a Mercator projection. It is only when you look at a globe that you can grasp what the “circumnavigation via the poles” – something Cowper has achieved twice, both east to west and vice versa – means.

It means hundreds of hours alone at the wheel, plugging on; of stifling fogs and brutal gales, and a vista of endless ice. Of bergs and bergy bits, and searching for elusive leads; of backtracking and frustration, danger. And always ice, the lure of which has drawn explorers north and south for centuries.

To Cowper the Arctic means “going into an antiques shop; back into history” where the shades and in some cases the bones of famous explorers still reside. Of McClure, Parry, McClintock, Franklin, Bellot and Ross, whose names are forever associated with straits, sounds and passages. There is now a Mabel E Holland Point at Fort Ross, near where she sank over the winter and Cowper raised her.

At his early Victorian house in Newcastle – formerly owned by the Barbour family – he stores a vast amount of gear, equipment and charts, as well as a collection of first editions of great explorers. Either he has a keen eye for their future value or, more likely, feels he is sailing in their wake.

“You can’t compare today’s voyagers with the old ones,” he says. “We are a relatively soft nation. They were pioneers – they didn’t know the answers. Scott was much maligned. Cook was a fantastic sailor. Should have been made a lord.”

A ghosted account of his Mabel E Holland adventures sold 10,000 copies, but he says that, although well written, he “didn’t really recognise himself in it”. Probing as to why he does it only elicits enigmatic or evasive answers. Finally he says: “Oh, it’s to get away from people”, with a smile that betrays the truth; for he clearly enjoys company, albeit of the right kind. “I don’t like people screaming at you,” he says. “Better to be on my own.”

Competent crew

There are clear exceptions: his son Freddie who accompanied him for several legs of previous voyages to Norway, the Azores and Iceland, and Jane Maufe, who shares his unflappable enthusiasm.

Maufe, fourth great niece of Rear Admiral Sir John Franklin, is retired from a Norfolk antiques business. “He told me I had ‘no annoying habits’,” she says. A “first class cook in all conditions,” adds Cowper. “We never missed a meal in all the time we were at sea. We eat exceedingly well.”

A highly competent crew, companion in adversity, diplomat, negotiator and fellow adventurer, she recalls being handed a Browning rifle at Fort Ross: “David wanders away completely unarmed with the bullets in his pocket and tells me that if I meet a bear I should click two stones together, then it buggers off.” It was a threat not to be taken lightly as a polar bear once “bounced up and down” on the Tinker Traveller that Polar Bound carries under a derrick on the aft deck.

Fact: Polar Bound is uninsured. “I just try to make sure everything is 100 per cent,” says Cowper.