The Golden Globe Race is deliberately ‘retro’, but are there lessons to be learned? Or is the race impractical in 2018-19?

The Golden Globe Race is a race like no other. It is a competition, an adventure, but also a celebration of an event that happened 50 years ago – the first ever solo around the world race in 1968. In designing the event, organiser Don McIntyre trod a difficult line between creating an authentic homage, but also building a new race that is relevant today.

Whether you think the Golden Globe Race concept madness or genius probably depends on whether you adhere to the view that traditional long-keeled yachts are the most intrinsically seaworthy.

In 1968 nobody knew what type of boats would perform best. “They weren’t the right boats last time around – Suhaili was not, Joshua was not, but they created unique stories,” points out solo racer Mike Golding, who has sailed through the Southern Ocean multiple times in BT Challenge yachts and IMOCA 60s.

Actually Robin Knox-Johnston’s first choice of vessel for his 1968 circumnavigation, a 53ft steel schooner, would not have been allowed under the new race rules.

The modern Golden Globe Race created a unique test in which 17 production yachts, all 32-36ft and designed prior to 1988, were pitted against some of the toughest ocean conditions imaginable. The fleet included six Rustler 36s, three Biscay 36s, an Endurance 35, Nicholson 32, and a Gaia 36. There was also one ‘new build’, a replica of the double-ended Suhaili.

On the face of it, they did not come out of it very well. Of the 18 entrants, 13 had retired by the time Jean-Luc Van Den Heede won in 212 days. Five were dismasted. Four of those were abandoned.

Article continues below…

A voyage for 21st Century madmen? What drives the Golden Globe skippers

A voyage for madmen, so was the original Sunday Times Golden Globe Race deemed. When the first non-stop race around…

Golden Globe skipper recovering in hospital after dramatic Southern Ocean rescue

Abhilash Tomy, the Golden Globe skipper who was dramatically rescued from the South Indian Ocean on Monday after nearly 72…

Three more had to stop racing after their self-steering systems failed. Others have been plagued by extreme barnacle growth and toxic mould, due to the sheer length of time spent at sea. The last skippers to finish were battling infections and food shortages.

But is such a rate of attrition surprising? Don McIntyre admits that the drop-out rate has been higher than expected, “As a gut feeling I didn’t think we’d have this low number of finishers, I was thinking maybe half or just less than half might have been realistic.”

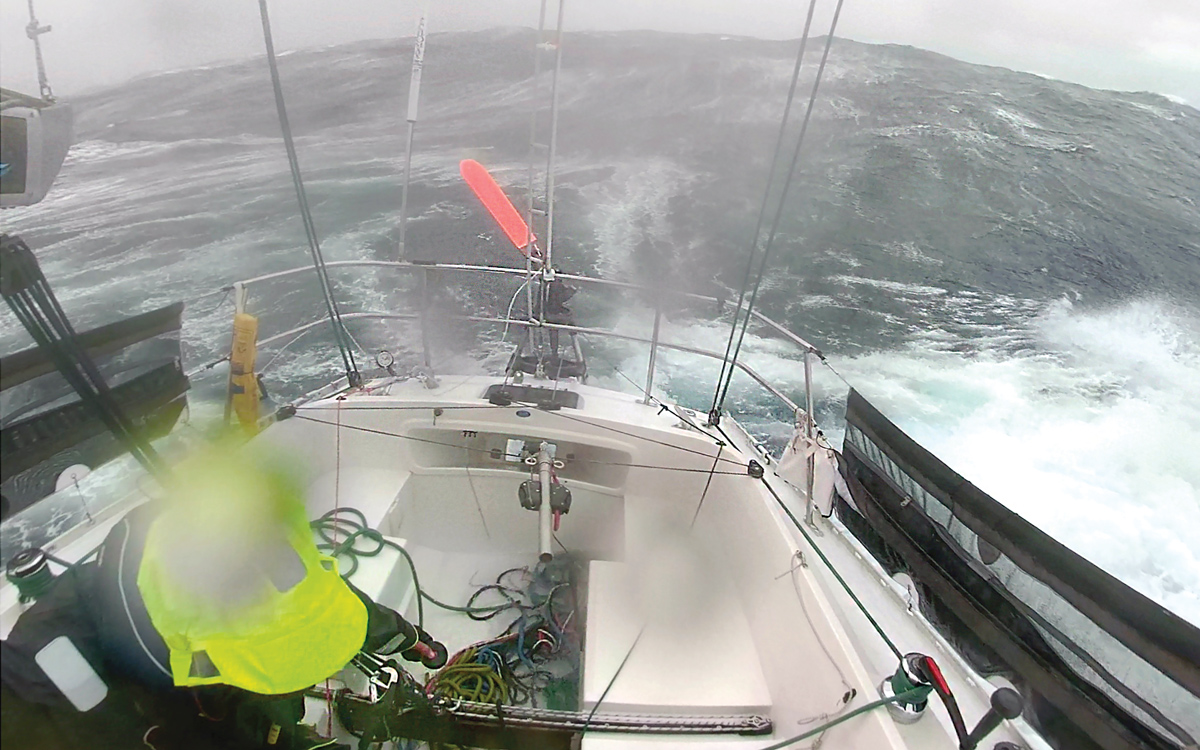

The biggest reason for yachts to withdraw was due to being rolled, by up to 360°, violently pitchpoled in waves, or severely knocked down during Southern Ocean storms.

“When boats are in the open ocean, size matters,” explains Merfyn Owen of Owen Clarke Yacht Design. He compares a stability curve for a long-keeled 36-footer and a modern bluewater cruiser.

“When boats are in the open ocean, size matters,” explains Merfyn Owen of Owen Clarke Yacht Design. He compares a stability curve for a long-keeled 36-footer and a modern bluewater cruiser.

The cruiser’s angle of vanishing stability will likely be at a far lower angle. “People might point to that and say the old boat is much more stable, it doesn’t have a vanishing angle until, say, 145°, so it’s a much safer boat.

“However, with a larger and/or modern yacht, especially with a deep keel and bulb, if you look at the righting moment – the top peak of the curve – it is likely to be quite a lot higher and the area underneath that curve is greater.

“It’s that area under the curve that is of most importance, because it’s directly equivalent to the energy required by a wave to roll the boat. The greater the area, the less likely to be rolled in the first place,” he explains.

The other key factor is speed: the long-keel designs are slow when compared, for example, to a modern Class 40. Typically sailing at 5-7 knots, skippers have little opportunity to sail away from severe conditions, and running before waves becomes difficult.

Storm tactics

The yachts’ relatively light weight is also a factor – the Rustler 36 is about 7.5 tons unladen. “I’ve done a non-stop round-the-world before on a 51-footer, it was a steel Buchanan, and it’s just a whole different game,” commented 2nd-placed finisher Mark Slats.

“That boat weighs 20 tons, so you can leave it beam on to the waves for quite a long time and nothing really happens. But on these little boats I get really nervous – the boat has to keep going forwards or you just get in trouble.”

There is also the question of whether boat handling in extreme conditions can increase sailors’ chances of avoiding knockdowns. This is something organisers asked Sir Robin Knox-Johnston to investigate – he released his report on 24 April.

There was no prerequisite to carry a drogue, and no briefing discussion of storm tactics before the start, although Slats says it was a big topic of conversation among the group of skippers he chatted with on the radio.

Gregor McGuckin was under bare poles and trailing warps in winds gusting 80 knots and confused seas when his Hanley Energy Endurance was dramatically rolled.

Gregor McGuckin successfully set a jury rig after his dismasting. Photo: Australian Maritime Safety Authority / PPL / GGR

In the same storm, which also saw Abhilash Tomy rolled and injured, Mark Slats first tried hand steering, then deployed warps before hauling them in (bare handed, having forgotten to pack gloves – a job which he estimates took one and a half hours) and sailing out of the low pressure system under windvane and storm jib.

“It’s really hard to say why I came through it and they didn’t – it could be just one wave,” he ponders.

Susie Goodall changed her storm tactics throughout the race. “Every storm is different. I used to deploy a drogue to slow the boat down,” she recalled in Hobart, saying she’d tried a new process approaching Tasmania. “But in [the] last storm, I simply towed warps and hand-steered to keep the boat stern-to and it seemed better.”

Abhilash Tomy suffered a spinal fracture when Thuraya was knocked down, but is making a good recovery. Photo: Australian Maritime Safety Authority / PPL / GGR

Van Den Heede never trailed warps, but always aimed to run with the breaking waves at a shallow angle to Matmut. “The mistake that I made when I was knocked down, I had an angle which was not big enough between the waves and [where they were] hitting the boat,” he said.

“I think if I had been 20° under the heading I would not have capsized, but we were sailing low to go down to Cape Horn. I went down too far.”

Solo cruiser Donna Lange has more experience of storm sailing in a small yacht than almost anyone. She has completed two circumnavigations in her Southern Cross 28, and has used many different tactics.

“I’ve tried everything. I have tried warps, but I didn’t have any luck with them. When I hove-to in the North Atlantic the sea anchor was fabulous. But you have to practice, because deploying it produced some incredibly extreme forces that I did not anticipate.

“It depends again on how your boat handles. Being a double-ender, my boat hobbies through the water and is really fantastic in big following seas. On my first trip I scudded: I was Knox-Johnston all the way! I just turned tail to anything and sailed it no matter how big the seas.

“It’s all about trying your gear and practising. Every ocean is different, so the techniques are different. In the Atlantic I could run under bare poles for hours, just cruising. I couldn’t do that in the Southern Ocean, I always had to have a hanky of a jib flying. It’s about being able to keep the boat powered up at all times.”

Steering issues

Windvane failures led up to two of the dismastings. According to McIntyre, Are Wiig was lying hove to in 35-40 knot winds because he was working on a repair to the coupling of his Monitor windvane.

McIntyre says Goodall had deployed her series drogue before she was pitchpoled because she too had been repairing a coupling on her Monitor. When her Rustler 36 righted one side of the drogue bridle had broken away.

Three competitors – Francesco Cappelletti, Nabil Amra and Philippe Péché, all carrying Beaufort windvanes – retired following problems with the vanes or the brackets.

Windvane reliability is an area organisers are looking to improve in the future. McIntyre is reluctant to prescribe equipment, but says they are considering making recommendations for the 2022 race.

The Golden Globe skippers relied on windvanes rather than modern autopilots. Photo: Jean-Luc Van Den Heede / PPL / GGR

“We don’t want to say: ‘You must have this windvane’. But maybe we start by saying, at this point, for these particular boats, we are happy with Aries, Hyrdovane and Windpilot. Any entrant who [wishes to use something else] has to give us a proposal as to why they believe it is suitable, and we will have to review that.”

On the positive side, the 30-footers may have been ‘domestic’ cruisers, but no keel or rudder issues were reported, and the only structural failure was on Wiig’s OE32. He was rolled 360° by a suspected rogue wave off Cape Town with such force that hull and deck cracked through, and a window staved in.

The rigs on both the 1st and 2nd placed finishers also survived extreme conditions. Van Den Heede’s developed a 5cm tear in the mast after being knocked down, and he is convinced that if he had not shortened his rig, he too would have been dismasted.

Before the race Mark Slats had worked hard to reduce weight aloft on his Rustler 36, and speculated that this may have contributed to its survival. He also reinforced all the chainplates before the start.

Abandonments at sea

That five boats were rolled and dismasted is remarkable in itself, but the fact that four were abandoned in the ocean is for many an unacceptable amount of collateral damage (some skippers were instructed not to scuttle due to local restrictions, other yachts are believed to have sunk).

“I think for any race that kind of rate of attrition is horrendous,” commented Dee Caffari, who recalls the 2008 Vendée Globe where just 11 out of 30 boats finished. “You are in the lap of Mother Nature and that is part of what you’re doing, but from a safety element it isn’t really acceptable.

Loïc Lepage dismasted 600 miles south west of Perth on October 20, 2018. He was rescued two days later. Photo: RAAF / PP / GGR

“And I think now the question is, is it acceptable for us to abandon these boats? Is it acceptable to leave it as a hazard or to break up in our oceans? Should we have a responsibility to scuttle our boat if we know we’re not going to have the funds to salvage it? It’s a conversation that has to start in our sport.”

Before the start, race organisers had placed a big emphasis on ensuring skippers were equipped to self-rescue or assist one another.

“Going right back to the concept of the boats we chose, we did it on the basis that they would be similar, so they would move as a fleet. It was always our philosophy that if something would happen the first person to assist [would be a fellow competitor],” explains McIntyre.

“In all the safety briefings we talked about ways of getting people on and off boats, even abandoning your boat to get onto a disabled sailors’ boat, we went through those protocols because that was what was expected.”

However, the distances between the yachts meant that in practice a ship could reach every stranded skipper long before another sailor. McGuckin set a jury rig and began sailing to the aid of the injured Tomy, until the French patrol vessel Osiris reached him first. A sailor in the Longue Route (a French event celebrating Moitessier’s voyage) headed towards Loïc Lepage, but a ship arrived sooner.

Are Wiig was dismasted 400 miles south-west of Cape Town on August 27, 2018. Photo: Eban Human / PPL / GGR

The Golden Globe is the only race that requires entrants to demonstrate they can set a jury rig effectively (using spinnaker poles) before the start. Wiig covered 400 miles to South Africa successfully under his. But Goodall lost DHL Starlight’s remaining spinnaker pole, boom and sails during her pitchpole.

There may be some creative solutions to this problem: Dick Koopmans, Mark Slat’s shore manager, says they built a joint which could couple two spinnaker poles together to build a taller jury rig, and even considered carrying a power kite that could be set without a spar.

Navigating by the sun

One of the most controversial ‘retro’ rules was the requirement that entrants use only navigation and communication devices available during the original Golden Globe.

Whilst this conjured up a romantic image of skippers listening to the shipping forecast while navigating by sextant, making no other contact with the outside world, the realities were quite different.

The banned equipment list meant skippers could not carry GPS, chart plotter, radar, or electronic wind instruments, but they could use radio, on both marine and amateur ham networks. Within the rules, this allowed skippers to set up a network of ham radio operators who could transmit forecasts to the sailors.

In practice, this meant a skipper could have an in-depth discussion with a radio operator, who could be looking at a modern computer with the tracker positions for all competitors, viewing satellite weather data, and comparing different forecast models.

As long as they were discussing publicly available information, and did not stray into routing – specifically giving directional advice – this was within the rules. Some competitors spent up to an hour every day discussing weather via the ham radio network.

Predictably, accusations of cheating were levied. On 20 February Estonian skipper Uku Randmaa, who was 3rd at the time, was given a 72-hour penalty after a recording emerged of a radio discussion where Randmaa is given advice that violated the rules.

Although originally the rules didn’t prohibit competitors from receiving position reports via radio, organisers were forced to reconsider and amend.

It also transpired that some operators were recording McIntyre’s weekly Facebook video updates, which included weather analysis, then replaying them to competitors. McIntyre began noting in his commentary which bits couldn’t be shared as they fell under ‘routing’. It all got very muddled indeed.

Things that can change

The 2018-19 Golden Globe was in many ways an experiment – almost as much of an experiment as the first race. Nobody could predict how running a 50-year-old-style race would pan out in an era of Facebook, sat comms, and wholly different attitudes to acceptable risk and environmental impact.

“We didn’t get it perfect in the first one. We had the ideas, but you never really know until you get into it,” admits Don McIntyre.

McIntyre says there will be changes for the next edition, planned for 2022, with some of the biggest being to weather and communication:

“We will only allow one type of weather, and it’s going to be the official text GMDSS weather report. It makes it tougher for the entrants, but I think it makes it more enjoyable.”

The timing of the race will also move. The Golden Globe faced criticism from many observers that its start, on 1 July 2018, plunged the majority of the fleet into the Southern Ocean too early in the season.

“We didn’t leave early, we left when we wanted to leave,” defends McIntyre. “But for the second edition the decision’s easy because 2022 has always been planned to celebrate Moitessier. He left on 22 August. Now that’s pretty perfect, because it’s seven weeks [later] and it balances getting to Cape Horn later versus arriving back [in France] in March.”

There will be a change to the course for 2022. Next time the fleet will have to round the island of Trinidade in the South Atlantic to port. “It takes out the whole issue of trying to cut through the South Atlantic High,” explains McIntyre. “That was challenging on the boats and it wasn’t enjoyable, because they had a lot of windward work.”

Other changes include an increase in the qualification requirements for skippers, doubled to 2,000 miles in the yacht in which they will enter.

Ultimately, the Golden Globe Race fleet may have experienced its fair share of bad luck, but impressive seamanship, the selflessness of rescue crews, and modern technology such as EPIRBs being available to deploy when really needed, meant even the skippers in the greatest peril have returned safely.

The Golden Globe is different from the established ocean races in every way, and it fills a very particular, yet surprisingly popular, niche in the short-handed calendar. It needs to avoid repeating the same problems in this edition, but with the mooted rule changes, the 2022 Golden Globe may be a very different beast.

There is every sign that another big entry will sign up. It seems there is plenty of appetite for the challenge of sailing slow, traditional yachts in the most extreme conditions imaginable.

Force 12 in a 36-footer

Mark Slats describes sailing through the most devastating Southern Ocean storm of the race on 20 September:

“First you get the north-westerly winds, and it goes up to 50 knots, 55, maybe gusting 60, but I was still sailing really fast and going good. Then the front comes over, and within two minutes it’s a south-westerly and it builds up to maybe 20-30% more than it was before.

“This time, I had the middle of the low pressure on top of me so my barometer went from 1010mb to 968 in five or six hours – I was looking at it thinking: is this real? I made a safety call to Don. He told me to get prepared for 70-80 knots.

“Then a big wave smashed the back of the boat, and took the sprayhood off, broke the door, the windvane, and it just filled the boat up with water to above the chart table. The boat went on its side, and kind of stayed there because there was so much water inside, at an angle of about 30-40°. I had no steering, but I had to prioritise, get the water out of the boat first.

“When the water was under control and I thought the electric pumps would catch up, I went outside and began hand-steering. I got very violently thrown overboard in a big knockdown, but the boat came back up and I got thrown back into the cockpit, all within 20 seconds – boom, boom!

“I said to myself this is not safe, so I threw lines out the back of the boat, so the boat would stay with the stern to the waves, still with the storm jib up, and went to fix the wind vane.

“Once I’d put the wind vane on, I immediately knew that it was doing a much better job than I had. It was dark, it was the middle of the night, you’re sitting behind the wheel and you hear one wave breaking on the starboard side and one on port, and you’re just waiting for the next one to break right on top of you.

“After that I had another four or five storms in the race, but they were all never more than 50 or 60 knots. You can have these storms that are just great, you know? Everything is just on the edge of control, and you’re in the middle of nowhere. I love that feeling, pushing everything to the maximum.”