Jonty Sherwill asks sailmaking guru Peter Kay how to get the best from your headsail to keep ahead of the fleet

The ultimate test of headsail trimming is the white heat of one-design racing and nowhere more so than at the start line. A perfect approach to the line on time and with pace will count for nothing unless you can stay with the competition straight after the start gun, climbing off boats to leeward and not falling into them.

But although an expert headsail trimmer is seen as critical to consistent upwind performance, that person is just part of a team that controls the rig tension, mainsail shape, boat trim and steering.

With so many variables during a race, those teams that deal better with fluctuating wind strength, dirty air and sea state will provide their tacticians with more options and sail a lot smarter.

1. You have a brand new headsail, the battens are fitted and it is ready for its first hoist. Don’t just haul it up. First, check the wind speed is inside its design range and don’t over-tension the halyard. Expect it to set well with a minimum of luff tension and a hint of compression wrinkles trailing back from the foil or hanks.

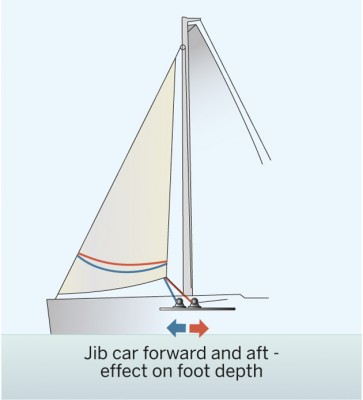

Set the car position so that, as the sheet tension gets close to fully on, the sag in the foot and leech is similar – think of it as the tension being equal in these two edges.

For a non-overlapping jib – and in the absence of a one-design tuning guide – set the inhauler just over the turn in the coachroof or use a tape measure or your phone’s calculator to mark the deck a distance of 0.174 x foot length off the centreline.

This position will set the sheeting angle at approximately 10° – the optimum sheeting angle can be anywhere between 7° and 14° depending on the particular design of the boat.

2. Don’t assume you can see enough of the sail shape from the cockpit. Go forward of the mast – it’s much easier to get an idea of the three-dimensional shape of the sail, where the maximum draught is located and what the vertical camber profile looks like.

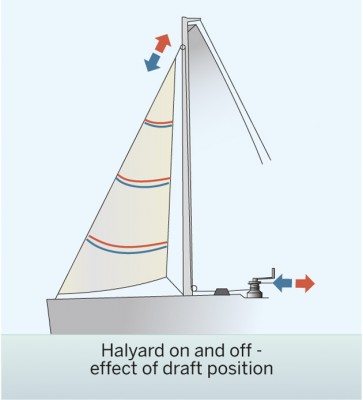

By observing the effect of changes in halyard tension from this viewpoint – extra tension dragging draught forward and rounding up the entry – it’s possible to have a better feel for calling halyard alterations here than from the more restricted viewpoint of the cockpit.

3. Starting from scratch on every occasion isn’t ideal – far better to reset the sail to a successful shape, then tweak that. To do this you need to mark up graduated scales for the track car position, halyard and inhauler.

Marks on the sheets and stripes around the spreaders (in the case of a non-overlapping jib) will let you get close to optimum settings after every mark and are also especially useful when setting the halyard tension at the leeward mark.

A call to ‘go up a point from last beat’s tension’ is more accurate than one that asks for ‘a bit tighter than last time’.

4. Although headsails are likely to have been designed for a specific wind speed range, it should still be possible to alter their shape through trimming so that the flying shape is optimised over that range.

In less wind than anticipated, the sail will need to be encouraged to develop power by sending the car forward to create more depth in the foot and by easing on the sheet to maintain twist.

To help achieve this, keep up the dialogue between the trimmers as they work together to find the sweet spot. For example, beefing up the headsail depth by releasing backstay tension and allowing more sag in the forestay may help the headsail, but what has it done to the mainsail trim?

Communication with the helmsman or tactician is also vital – although a trimmer may intuitively feel that he needs to power up to maintain speed as the breeze goes light, trying to maintain a lane or push for height to clear an obstruction, for example.

5. A sail will change shape as it ages over the course of its life. Typically, a laminate sail will shrink in the front and stretch in the back, so that more halyard tension will be needed to maintain the draught location in the correct place. As the established fast settings start to drift, it’s important to go back to first principles occasionally. Get onto the foredeck and take a really close look at the sail shape and recalibrate your settings to achieve the best possible performance.

Peter Kay was chief designer at North Sails UK in the 1980s and was involved in three America’s Cups. He started Parker & Kay Sailmakers in 1989, later associating the business with worldwide groups Quantum and latterly OneSails. As a sailor he has won national titles in the Snipe and OK dinghies, as well as European and World titles in 6-metres and Swans.

This is an extract from a feature in Yachting World June 2014 issue