In Part 2 of our series Dan Bower gives detailed advice on entering tricky coral passes and the use of Mk1 eyeball combined with more modern techniques

A deserted tropical paradise is getting harder to find, particularly in the busier Caribbean Islands where the number of visiting yachts means that any straightforward, well-marked pretty bay is full to bursting.

A deserted tropical paradise is getting harder to find, particularly in the busier Caribbean Islands where the number of visiting yachts means that any straightforward, well-marked pretty bay is full to bursting.

However, with a little work and skill there are still little treasures to be uncovered. Even in peak season in the British Virgin Islands, for example, you can find your own private spot – if you’re prepared to do a bit of eyeball navigation pilotage.

In the Pacific and further afield this becomes more of a necessity. With the exception of commercial harbours, most of the islands in the South Pacific and Indonesia don’t have much in the way of manmade navigational marks, and the only shelter to be found is inside the coral lagoons. Nagivating in coral and getting through a reef pass is the only way to experience the idyllic atolls that most yachtsmen are looking for.

Navigating an unmarked pass

This is one of those rare opportunities that requires going back to basics with pilotage and navigation skills. We are so used to trusting our chartplotters implicitly that the notion of your eyes being right even when the display clearly indicates something different is a touch disquieting.

In the main, I believe our navigation software. When it shows the very berth I’m tied to, it’s hard not to be impressed, but further from home accuracy cannot be assured and you can become unstuck. In a well-documented case in 2010, a Clipper round the world race yacht hit a reef the crew thought they were missing by over a mile.

The problem is not the GPS, it is the charts. Many are reliant on data from the 1860s, with positions derived from surveys using a sextant and visual fixes. This causes two main problems: charted passages may not be sufficiently detailed or accurate; and you may not be where your GPS thinks you are. This is known as chart offset and applies particularly in the South Pacific islands.

Don’t despair, the charts are a very good representation of what exists, but they need to be taken in context. Visual pilotage is actually easier than ever if you have a good radar set, forward-facing sonar and satellite photos courtesy of Google Earth.

Key points for a coral pass

It is important to enter on your own terms and in your own time. If possible, consider a close alternative anchorage to wait for the optimum conditions and perhaps even check out the pass with a dinghy. Speak to other skippers who are already in (or have been in), visiting by tender or speaking to them on a radio net.

Make sure you plan your arrival time and only enter if the conditions are right.

Tidal flow – slack water is the optimal time to enter, and even then there will be wind-driven current in the pass. The ebb tide is the most troublesome, with a higher flow rate and increased risk of standing waves. (Slack tide can be found in publications or calculated as 12 hours from moonrise/set).

Sunlight is the most important consideration, as you need to be able to see what’s under the water, so the sun must be high, and preferably behind you. Overcast or even short-term cloud obscuring the sun affects what you can distinguish.

You need a good pilotage plan, principally how to confirm your position with the chart: for example, visual fixes, contour lines, transits, clearing lines and back bearings.

Satellite imagery comes with many chart packs or can be obtained in advance from Google Earth and that will help you to familiarise yourself with the passage. Georeferenced images can also indicate chart offset if overlaid on your chart.

Ready to enter?

Get the engine on, the sails down (but lash the main halyard so the sail is ready to hoist again quickly if your engine fails), the crew prepared and briefed. The crew are going to be your pilots so familiarise them with the charts and photos.

Agree hand signals or commands if using a headset. Clear and practised communication is critical. Are they pointing to a danger or saying go that way?

Identify your position. Is it correct relative to the chart? Confirm with visual fix, spot depths, radar overlay and good old MkI eyeball. Some chartplotters allow you to alter chart offset manually, allowing you to move your position relative to the chart. This can be useful, but do not rely on it.

Make a mental note of your line of retreat, or place of refuge. That sounds pessimistic, but it’s better to have a bailout plan – even if you don’t need it, it will make you feel a whole lot better! This is a time for the GPS: record your track so you can follow it in and out.

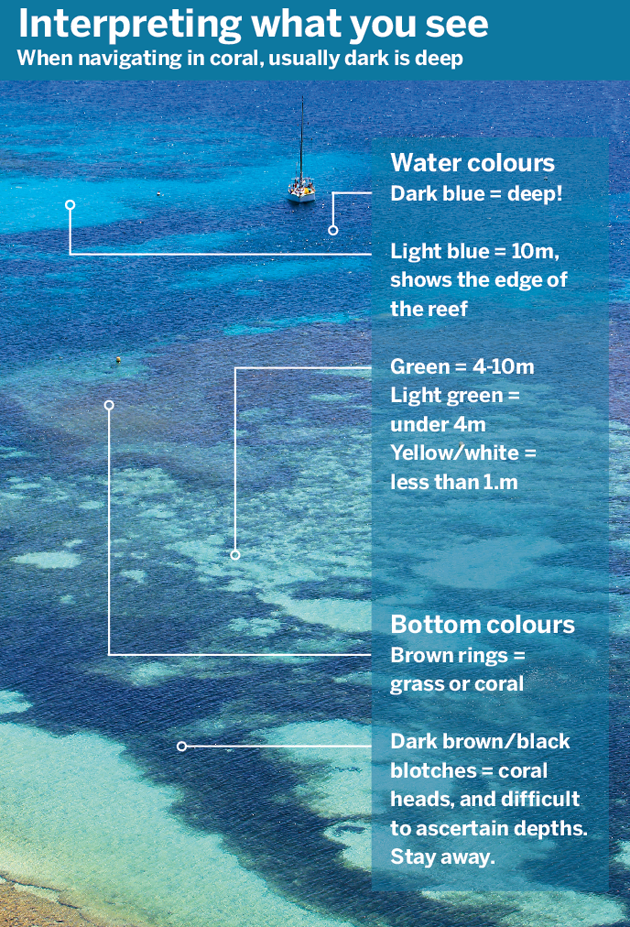

Keep your eyes primed. Reef navigation is all about the eyeball, so you have to give them their best chance. The main thing that helps is height. An aerial view is much clearer than a view from the deck, so consider sending a crewmember up to the spreaders to con you in. If you have crew to spare then post another on the bow. Polarised sailing sunglasses can help cut through the glare.

If crew numbers allow, place someone competent at the helm so that the skipper can pilot the boat in. That way you’re free to take bearings, worry about the chart (literally) and move to the best vantage points – you have enough to do. The helmsman can concentrate on steering.

Keep an eye on the currents. Around reefs these can be strong and variable, and often flow towards danger; it’s not uncommon to have sideways currents at the entrance to a pass, so monitor your ground track.

Proceed slowly and look where you’re going. Having a pilotage plan is great, but remember it is only as good as the chart. Place trust in your crew and depth sounder. Forward-facing sonar is useful if you have it.

Usually a coral pass leads into a clear and safe lagoon – hopefully the paradise you were looking for. Consider your anchorage point and aim for a sandy patch as anchoring in coral is, if not illegal, irresponsible.

It is a good plan to save your track because then you can find your way out along a known safe route. Consider taking off a couple of waypoints and transferring them to your chart – belt and braces if your track gets lost – and can be useful for a future visit.

Entering Mana

Entering the pass at Mana in Fiji is tricky, as we show in our video above. It is narrow and twisty, poorly marked and has a strong ebbing stream. Once you are in the pass there is no option to abort as there is simply not enough room for you to turn around safely.

Our charts, which are up to date and the best you can get, show no pass into the island, or any lagoon at all. We had a hand-drawn sketch chart from a pilot book, but without any reference points.

We used a Google Earth overlay to provide an idea of what we would be entering, and we transferred waypoints from that onto our on-deck GPS to give us something to go on, but from that point on, it was all about eyeball navigation.

With one person up the mast, one on the foredeck, motoring just fast enough to keep steerage we threaded our way through the reef, avoiding some mid-channel coral heads.

Satellite images are available as bolt-ons with proprietary chart packs, or it is possible to make your own with Google Earth using open source software (GE2KAP), or download charts from the cruising community who have put them together for the greater good. For instance, for the Pacific an amazing resource has been compiled by cruising sailors Sherry and Dave aboard Soggy Paws – http://svsoggypaws.com/files/.

You must test for yourself the accuracy and limitations of these. They are only available for a computer-based system and need navigation software to overlay the GPS position. Not all programs will recognise them as charts. A free, simple package is OpenCPN.

Do’s and don’ts

√ Do agree hand signals with the crew. Are they pointing where to go, or to the danger? (We point to a danger, or wave in the direction we want to go)

√ Do use floats at intervals on your anchor chain to minimise the chance of getting the chain wrapped around coral heads

√ Do remember dinghies and outboards can also be susceptible to coral heads where it is very shallow

x Don’t forget local advice. Radio other yachts in the anchorage (isn’t AIS great?) as they may have local advice about the passes and where is clear or foul for anchoring

x Don’t assume charts are accurate. Atolls and lagoons have patches that are unsurveyed, so great care is needed here.

Top tips

- Get a pair of good-quality polarising sunglasses; they will help you see below the glare on the water surface. Here we are holding up a polarisign filter to show how it works

- Rain run-off from rivers will affect water clarity, so consider the conditions and local terrain, and proceed cautiously if the water is cloudy. Get someone aloft if possible.

- It’s easy to confuse dark patches cast by cloud shadows with coral heads, so you’ll need to interpret as you go.

- Proceed with great caution if it’s overcast, and if possible make sure the timing of passing clouds or squalls won’t coincide with a critical phase of eyeball navigation.

- If going through a running pass or breaking into a coral atoll, take great care: there is likely to be current against you. There may be less current at the edges of the pass.

- If there is a choice when entering a coral pass, always take the leeward one, but if there isn’t, try to enter at slack tide or on the flood to minimise the sea state or any standing waves.

- When leaving, you will have current with you and your SOG will be greater, so retrace your original route carefully.

- If in doubt, use your GPS track to retrace your route and wait for another time – or day if need be.

Dan and Em Bower

Dan and Em Bower, both in their thirties, are lifelong sailors. Six years ago they bought Skyelark of London, a Skye 51 by American designer Rob Ladd, built in Taiwan in 1986, and have been sailing and chartering her ever since, making some 12 transatlantic crossings and covering around 60,000 miles.

Part 3: Coping with squalls

How to prepare for and deal with those sudden squalls you face in the Tropics

See videos for all the parts here

12-part series in association with Pantaenius