Shane Granger and crew suddenly find themselves without a rudder in a tropical cyclone. Tom Cunliffe introduces this extract from Cargo of Hope

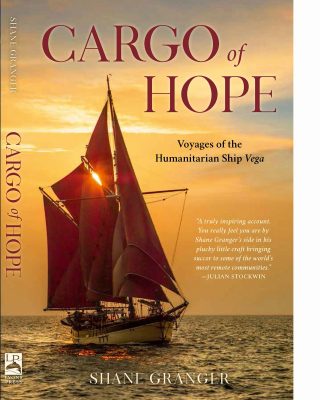

Perhaps the best way to introduce Shane Granger is to quote from the flyleaf of his book Cargo of Hope: ‘He has worked as a radio DJ, advertising photographer, copywriter, boatbuilder, director of museum ship restoration and bush pilot, between traipsing across the Sahara Desert, being kidnapped by bandits in Afghanistan and chased through the Andes by an assortment of revolutionary lunatics, but he has always returned to the ocean.’

The ship he shares with his partner, Meggi, is Vega, a 55-ton wooden commercial sailing vessel built for service in the Norwegian Arctic 130 years ago. He and Meggi live on board, dedicating their lives to sourcing and delivering educational, environmental and medical supplies to remote island communities in eastern Indonesia and East Timor.

We join them caught in the heart of Cyclone Gafilo, the most violent cyclone to hit the Indian Ocean in over 10 years. Things are not looking good for Vega or her redoubtable skipper…

Extract from Cargo of Hope

Extract from Cargo of Hope

Ripping through an ominous sky blacker than the inside of the devil’s back pocket, a searing billion volts of lightning illuminated ragged clouds scudding along not much higher than the ship’s mast. Through half-closed eyes burning from the onslaught of wind-driven salt water, I struggled to maintain our heading on an ancient, dimly lit compass.

This was not your common or garden-variety storm. The kind that blows a little, rains a lot, and then slinks off to do whatever storms do in their off hours. This was a full-blown, rip-roaring, Indian Ocean cyclone fully intent on claiming our small wooden vessel and its occupants as sacrifices.

Using both hands, I turned the wheel to meet the next onslaught. Should I miscalculate or lose concentration, within seconds the boat might whip broadside to those enormous thundering waves, allowing the next one to overwhelm her, rolling her repeatedly like a rubber duck trapped in someone’s washing machine: shattering her stout timbers and dooming us all to a watery grave.

Only 20m away, the bow was invisible in a swirling mass of wind, rain, and wildly foaming sea. With monotonous regularity, precipitous walls of tortured water loomed out of the darkness, rushing toward Vega’s unprotected stern. Yet, as each wall of water raced toward her, its top curling over in a seething welter of foam, our brave little vessel would rise, allowing another monster to pass harmlessly under her keel. With each wave, the long anchor warps trailing in a loop from our stern groaned against the mooring bits.

Tormented seas

Those thick ropes were all we had to reduce Vega’s mad rush into the next valley of tormented water, their paltry resistance all that stood between us and 52 tons of boat surfing out of control down the near-vertical face of those waves. As Vega valiantly lifted to meet each successive wave, she dug in her bow, a motion that unchecked might rapidly swing her broadside. Our future was contingent upon a single scrap of storm sail stretched taut as a plate of steel, its heavy sheet rigid as an iron bar. Without it, steering would be impossible.

I should have paid more attention to the old sailor who once advised me never to look down when climbing ratlines or aft during a storm. It might have saved me from almost suffering an apoplexy when somewhere around midnight I glanced astern and saw a wave much larger than the rest come roaring out of the darkness, growing in height and apparent malice with each passing second. As if that were not enough, another rogue wave came surging out of the night at a 90° angle to our route.

Nothing in my years at sea had prepared me for that giant storm-ravaged whitecap bearing down on Vega’s starboard beam. Frozen in horror, I watched it collide with the first giant wave, roaring along its length like a head-on collision between two out-of-control avalanches.

A towering eruption of white water rocketed skyward, an unbridled violence beyond imagination. Clearly, both waves would arrive at the same time. One would slam into Vega like a huge bloody-minded mallet, while the other played the part of a watery anvil, and there was not a damned thing I could do about it.

No matter which way I turned the wheel, one of those furious monsters would roll Vega onto her beam-ends. Certain destruction would surely follow. Trembling from cold and fatigue, there was just enough time for me to take a deep breath before water erupted from every direction.

Hoisting Vega’s outer jib in a stiff breeze. Photo: Shane Granger

I gripped the steering as hard as I could, frantically struggling against forces fully intent on sweeping me overboard, to turn it against the sideways slide I felt building. Then something struck me a fierce blow to the head. As I began to lose consciousness, my only thought was, So, this is how it ends. Then my world turned black.

Battling up from the depths of unconsciousness is a bit like rebooting a computer; everything starts over again from the here and now, not there and then. I fought my way back to the wheel from the lee scuppers and turned it three spokes to port. The wheel’s resistance felt strangely light.

As I waited for Vega to respond, the compass obstinately remained fixed on the same heading. When another two spokes to port also brought no result, I began to worry.

Article continues below…

Out of control

Just then my partner, Meggi, who had been safely ensconced in our aft cabin bunk, stuck her head out of the aft hatch. Screaming to be heard over the raging wind, she informed me an ungodly great rending crack had come from where the steering ram is located just behind our bunk.

Leaving the helm to Meggi, I made my way into our cabin and lifted the steering box cover. The hydraulic steering ram shaft, made from 1in diameter high-tensile machine steel, had shattered like a cheap plastic toy, leaving the tiller arm free to thrash back and forth.

Vega was out of control. Only the drag generated by those long mooring ropes and the thrust of our storm jib held her before the waves. Without steering, there was nothing to stop Vega from broaching sideways and being rolled mercilessly into oblivion. It was then the real horror of our situation dawned on me: the rudder was not only swinging from port to starboard, fully at the mercy of the sea, it was also rocking from side to side. One of the pintles had broken.

They say time flies when you’re having fun. What they fail to mention are the moments when time simply shrugs her shoulders and wanders off looking for a cold beer, leaving you in limbo to carry on as best you can. I yelled for Meggi to get out the emergency tiller, while I fought my way back up on deck and retrieved two pieces of stout braided line for an emergency rudder repair.

Built 130 years ago, Vega requires physical and strenuous rope handling by the crew for every sail change or manoeuvre. Here trimming Vega’s headsails in 20 knots of wind. Photo: Shane Granger

What in port, on a calm day, would have taken me only minutes to accomplish became an endless eternity. Before the emergency tiller could be put in place, I first had to dismount the remains of the shattered steering ram. That involved removing a tight-fitting stainless-steel pin held in place by a reticent split pin.

Just getting the locking pin out was a major effort involving pliers, hammers, bashed fingers and copious amounts of creative profanity. Then the big pin had to be pulled, a job that became a marathon of horrors. Through all of this, I was relentlessly under attack by a flailing rudder and its heavy iron steering arm.

The strange thing about life-or-death situations is how they can focus your mind in two different directions. One instinct is to widdle your knickers and hide under the bed with your bum in the air and a pillow covering your head, while another little voice between your ears is screaming at you to do something before you find out if there really is a man with a scythe on the other side.

Vega delivering educational and medical supplies to the Indonesian island Banda Neir. Photo: Shane Granger

Emergency steering

With the remains of the steering ram out of the way, another interesting little quandary presented itself. How to firmly reattach the rudder head to the boat so that when I had the emergency tiller in place the rudder would actually pivot and not simply flop from side to side. That is where my two pieces of braided yacht line would come into play, if I could get them in place without losing a handful of fingers – or worse.

Fortunately, there was a space between the steering arm and the rudder head. If I could reeve the two pieces of line through that space, and bowse them tightly to the sides of the boat, together they would hold the rudder head, more or less, on the centreline so it could be turned.

The biggest problem was getting the two lines through such a small space while retaining all of my appendages and avoiding a short sharp smack on the head from the flailing rudder arm. How long it really took, I have no idea.

Once I threaded these lines between the rudder head and steering arm, I anchored them firmly behind the beam shelf both port and starboard, effectively wedging them against two stout frames. That done, and after some anxious moments getting the close-fitting emergency tiller slotted over the steering arm, we could steer again. How we were still alive and not well on our way to Davey Jones’s locker is still a mystery.

While I cursed reticent lines and rudders in general, and sucked on fingers mashed with disconcerting regularity, Meggi duct-taped our hand-bearing compass to a deck pillar so we had something to guide us once steering was restored below decks.

Vega under full sail. Photo: Shane Granger

With the emergency tiller in place and a compass to steer by, I gave the tiller an almighty shove to starboard. Nothing happened. Leaning into it with all my strength, I barely managed to shift the blasted thing by a few degrees.

Little wonder the rudder was hard to budge. The original tiller on a boat like Vega would have been between four and five metres long and required one and sometimes two standing men to shift it. The emergency tiller our lives now depended on was a little over 1.5m and can only be operated from a sitting position. Calling our two young crewmen, I put one on each side of the tiller and gave them a course to steer.

It is amazing what fear can do for your strength and endurance. Considering the wild gyrations our boat was making, just staying in one place was a major effort, much less applying force to steer. Yet somehow, those two intrepid lads managed to get us back on course.

Leaving them to grunt and groan over the tiller, I went searching for a few pulleys and some line to rig a relieving tackle, a devious sailorly invention consisting of four blocks rigged on a single line in such a way that when half the tackle pulls the other half pays out. In our case, the four-to-one mechanical advantage I cobbled together meant one person could steer the boat, more or less.

Skipper and author Shane Granger. Photo: Shane Granger

A survivor

Many large ships and fishing boats were lost in that tempest, yet thanks to her builder’s skill and proven North Sea heritage, Vega survived. What we desperately needed now was a safe port, to repair our shattered hydraulic steering ram and rudder. A place to rest and recover.

The closest safe haven was Victoria Harbour on the island of Mahe in the Seychelles. With the fragile state of our steering, winning those few hundred miles would be a difficult task – perhaps even impossible, but we had three minutes left on our satphone and our friends in London came to the rescue.

They contacted the port authorities and Coast Guard in the Seychelles, advising them of our location, current course and speed, and our intention to enter their port. They also advised that we had serious steering problems. It was a good thing they did.

Three days later, we arrived safely off the entrance to Victoria Harbour.

Buy the Cargo of Hope from Amazon

Learn more about Vega’s work

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Extract from Cargo of Hope

Extract from Cargo of Hope