As an experienced skipper, ARC weather man Chris Tibbs describes what he looks for in a good crew member to cross the Atlantic with him

Matching skippers and crew can be a difficult process and while there are characteristics we can identify in a good skipper, there are also some points that need to be made about being a good crew member.

When I sailed on large racing boats it was often joked that the foredeck crew were like mushrooms – kept in the dark and fed on manure (although that wasn’t the word used). When it comes to cruising it should be somewhat different as not only are you going to have to sail together, you will be living together for a period of time.

This might be three weeks or more for a transatlantic crossing and even longer in the Pacific. It is therefore important that crews, skippers and owners all get along, not only on the sailing side, but also socially living in a confined space.

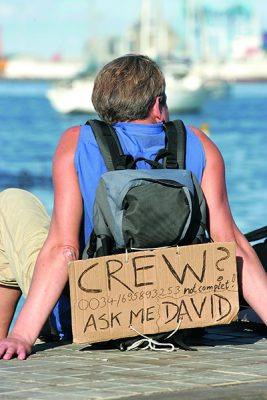

It is almost impossible beforehand to know how well you will get on together, and experiences from the ARC can be mixed. Good friends might fall out, yet crew joining at the last minute – sometimes having only briefly met in a bar – have worked out brilliantly.

See also Chris Tibbs on How to be a good skipper

Good company

I find that the older I get the more important it is that I enjoy the company of the people I am sailing with whether as crew or skipper. After a long passage or extended cruise it would be nice to think that we are all friends for life. This sometimes happens, but at other times yachts might arrive at the end of their transatlantic with crew leaving as soon as docklines are made fast.

So what makes for a good crew and a harmonious passage? A passage is a combination of many parts and is much more than just the pure sailing. There will be problems and some gear failure and how this is dealt with will reflect on everyone’s enjoyment of the passage.

With a long racing background it is important to me that the boat is sailed safely and efficiently, but unless in a race, at the end of the passage we generally remember how much we enjoyed it rather than the time taken, although for a rally there is that all-important finishing position!

Willing and flexible

At the top of my list is for willing and flexible crewmembers. Although I am well aware that everyone has an opinion, and I am happy to listen, any decision is ultimately the skipper’s responsibility and we have to live with the consequences of that decision. So once your point has been made respect the skipper’s decision; it is very divisive when crewmembers either continue to challenge the skipper or take an “I told you so” attitude.

For a crew looking for a position honesty is important, particularly about ability and experience. Don’t brag as there is likely to be someone on board who has sailed in bigger winds and seas, or further and longer than you, so you will be caught out if you’re embellishing the truth.

It is also useful to share expectations for the trip, such as what you want to achieve and learn. An honest appraisal of seasickness and how much sleep or food you require is also important so differences can be discussed and, from a skipper’s point of view, knowing who may be incapacitated by seasickness helps in planning watches.

Be tidy with your own kit and also the boat’s kit. Nobody likes being woken by the on watch searching for something that has not been put away. When sailing in the tropics, typically a transatlantic, there are almost 12 hours a day of darkness, so knowing where your kit is and being able to find it at night is important.

Likewise it is not difficult to learn where each rope on the boat leads, and which jammer is which. However it is difficult to helm when flashlights are continually being switched on and off to identify a rope that is constantly being used. The use of lights on a dark night is occasionally necessary, but it is also important not to destroy night vision. A little thought about where light switches are, which ones are for red lights and where the more usual lines lead will help relations with other crewmembers and the skipper.

Living together

A long passage is not just about sailing; we all have to live together and get along and this starts in the galley and below decks just as much as in the trimming of sails and helming. There will be natural divisions as skills vary and some will be more comfortable in the galley than on the foredeck, however keeping the boat running and keeping up with maintenance as well as with repairs and food are just as important. A long passage is a team effort not a competition so give other crewmembers a chance.

Night watches go by quickly with good conversation and interesting discussion. Away from phones and computers on a long ocean passage you have time to talk. People are interesting and asking crewmates about themselves can be very revealing.

Ocean passages tend to throw together a wide mix of people with interesting stories; it is a shame to dismiss anyone just because they have not done a great deal of sailing. There will often be hidden talents on board that for the asking go unnoticed.

Although we all get tired and grumpy on occasion, we need to be tolerant of others and an angry response will take a lot of undoing; sometimes it is better to bite your tongue and not respond in the heat of the moment. If something really is bothering you, better to address it at a later, less stressful time.

Notes from a skipper/owner

Having run boats professionally and now having our own boat and cruising, perspectives do change somewhat.

We are allowing people onto our pride and joy, so every bump, scrape and ding is felt almost personally. I want crew to be very careful with things like safety harness hooks as they cut chunks out of the varnish very quickly. It costs a lot to keep a boat well maintained, so carelessness quickly becomes irritating.

Personally, I find laziness a cardinal sin. I have seen crew that are lazy on deck, lazy in the galley and generally not pulling their weight. Enthusiasm is everything and while I will easily forgive a lack of knowledge, as the sailing side of things can be taught, lack of care and avoiding their fair share of the chores is unforgivable.

Respect boat rules – if no wet oilskins are allowed below try to respect this. Most boats have some rules that are usually not very onerous and are there for a reason.

Money may well raise its ugly head and having clear ground rules ahead of the voyage helps – it is an expensive business taking your yacht on long voyages. The boat is legally responsible for repatriating crew although most cruising yachts expect crew to fund their own travel.

Small acts can make all the difference – on our last crossing with the ARC not only did our crewmembers take us out for our crew dinner at the end of the rally, they also bought pictures of us crossing the finishing line. Both were unnecessary, but a really nice thank you.

Aggravating habits

When an old racing friend was asked what he would like for the boat his answer was always for a “glass crew”, as there always seemed to be someone in the way to spoil his view of the instruments or when docking. My own pet hate is talking to the wind. It is impossible to hear what is being said when crew talk into the wind, rather than to the person they are trying to communicate with. It is a simple thing, but as communication on board is so important it’s best to be clear with it.

And finally, don’t argue – once a decision is made get on with it. Adding doubt to a difficult decision or rehashing an argument is wasteful in time and effort and sometimes things have to be done in a hurry. There will be time afterwards, over a cup of tea, to talk through manoeuvres and what might be done better in future.

Putting a good crew together for a passage is not always easy. Getting time off work for long-distance cruising is just not possible for most people so you will often end up sailing with people that you do not know very well. Sometimes this works out perfectly, but other times it can be a bit of a disaster.

It would be nice to have a trial or demo sail with prospective crewmembers, but this is usually not possible so compromises have to be made. At the end of the ARC there are always interesting stories, but it must be said that the crews of the vast majority of yachts crossing the Atlantic arrive as friends and boats with significant crew conflicts are few and far between.

Chris’s own crew for crossing the Atlantic aboard his yacht Taistealai

5 tips for a good crew

- Be willing and flexible.

- Honesty is important, particularly about ability and experience.

- By all means contribute to any discussion, but respect the skipper’s decision.

- Be prepared to muck in with all onboard chores equally.

- Be tidy and careful – this is someone’s home.

Chris Tibbs is a meteorologist and weather router, as well as a professional sailor and navigator, forecasting for Olympic teams and the ARC rally. He is currently on his own circumnavigation with his wife, Helen. His series of Weather Briefings can be seen here

See also:

Chris Tibbs prepares his own boat for an Atlantic crossing

The best route for an Atlantic crossing

Taking the northerly route across the Atlantic

Offshore weather planning: options for receiving weather data at sea

as well as Chris Tibbs’s series of Weather Briefings

Also….watch this video interview of Paul Dunn, who crewed on a German yacht in the ARC. He had never met the three other crew before, but they had a great time. The experience gave him some interesting insights