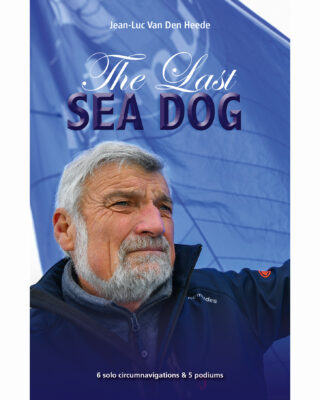

Tom Cunliffe introduces this extract from Jean-Luc Van Den Heede's book, The Last Seadog about his Golden Globe Race win in 2018/19

For any sailor interested in single-handed racing, Jean-Luc Van Den Heede’s The Last Seadog, just published, is a more than welcome addition to the bookshelf. The ultimate French solo ‘navigateur’, Jean-Luc, now well on in years, stands out among the catalogue of remarkable characters who sign up for these gruelling events.

After six circumnavigations, including two podiums in the Vendée Globe and two in the BOC Challenge, he crowned his career with outright victory in the 2018/19 Golden Globe Race.

The book outlines his life, majoring on the Golden Globe event. As most of us know, this is a very different kettle of fish from the high-tech races in which he made his name.

It is run for boats similar to those available when Sir Robin Knox-Johnston won the original event 50 years earlier. No electronics are allowed, there’s no satnav, and virtually no communications beyond the basics of safety.

The book starts with a description of a severe knock-down in the Southern Ocean that leaves Jean-Luc with a badly damaged mast. The remainder of the chapter describes not only the damage and what might or might not be done about it, but offers a revealing insight into the mindset of a man who is first tempted to give up, retire from racing and call it a day, only to be driven one more time by the inner demon that refuses to capitulate to what most would see as catastrophe. His thought processes are an inspiration. That he goes on to win the race by a significant margin passes almost without saying.

Extract from The Last Seadog

Extract from The Last Seadog

With the regularity of a cathedral bell, the waves crash against the starboard side of my boat. Powerful and vicious at the same time, they are not only violent but the noise they create inside the dark cabin turn it into a giant, echoing drum, further increasing the level of threat and stress.

I’m on high alert. My boat rocks from side to side with the relentless determination of a metronome. This is not the first time I’ve faced a storm in these vast expanses of the Southern Pacific Ocean, far from any land. I have confidence in my boat, my floating safe. Nevertheless, the situation is worrisome and it’s only because I’m exhausted from the sleepless night before that I manage to close one eye.

The respite is short-lived. Without warning, all at once, I’m thrown out of my bunk.

I roll and get squashed – like a fly – with all my weight (all 90 kilos of me) against a locker. Another second and I find myself stuck to the ceiling of the cabin. I’m half-conscious. Between dream and reality, I hear heaps of objects falling in an indescribable chaos and clamour, until the fridge door opens, releasing a cascade of provisions suddenly turned into projectiles.

As proof of the ferocity of this onslaught, the floor hatches, covering the batteries in the bilges, burst open despite the safety latch and the heavy bag of medical kit placed on top of them. There’s no doubt, I’ve capsized, or at least performed a serious somersault. From 130°-140°? Or 150°? It doesn’t matter. My brave Rustler 36 was hit hard and took a blow, insidious but formidable. A real uppercut.

In an instant, the boat rolls in the opposite direction and I find myself upright again. By some miracle? The heavy keel, which represents almost half the weight of the boat on its own, played its role. Thank God. I move and regain my senses. Nothing seems to be broken, minor bruises perhaps, but no serious injuries.

In the chaos I locate my boots and my wet weather jacket, climb on deck and peer into the darkness to see what damage has been done. The mast is still standing but the shrouds are slack and the mast rocks from side to side in the menacing Southern Ocean swells.

The canvas companionway dodger, which allows me to steer in shelter, is literally torn apart, its stainless-steel frame twisted like pieces of flimsy wire. I’m not feeling great, but I pull myself together. Now is not the time to be demoralised. I grab the flashlight at the bottom of the companionway steps and head back onto the deck for a thorough inspection.

The night is pitch black. The wind is blowing furiously. I roughly estimate the waves to be around 9m. I hang on to my bucking bronco of a boat. ‘One hand for you, one hand for the boat’, the saying is more relevant than ever – especially since I’m not connected to any lifeline and I’m not wearing a lifejacket. I know it’s not sensible, but I didn’t have time to put it on, and anyway, in this situation, it wouldn’t be very useful since I’m alone on board, and the nearest competitor is more than two weeks away from my position.

Article continues below…

Anticipating the worst

Forty-eight hours earlier, the race management warned me about a strong storm. All I saw was the needle of my barometer in freefall, a sure sign (that does not lie) of bad weather to come. The radio amateurs I could speak to on my high frequency radio also confirmed a storm with south-west winds at Force 11 (103-117km/h or 64-72mph) gusting to Force 12 (over 117km/h, or 73mph – hurricane strength winds on the Beaufort Scale), accompanied by waves the size of a three-storey building.

I was sailing with a beam wind at about 2,000 miles from Cape Horn on this 5 November 2018, almost routine after 126 days of sailing since starting at Les Sables d’Olonne, France.

From time to time a stronger and higher wave crashed into the hull and over the boat. Although Matmut is fairly stable under sail thanks to its good beam width, I was worried but focused.

Inspiration from a Joshua Slocum image on Matmut’s saloon bulkhead

After completely lowering my mainsail, I was left with only a tiny scrap of canvas at the front. In anticipation of the worst, I made sure to secure and tie down everything that could be secured. However, I did need to rest as soon as possible. In a near sleepwalking state, I noted in my logbook, a 21x 29.7cm school notebook with small squares and a red plastic cover: ‘Wind 50 knots and more, seas frothing’.

Perhaps it was a coincidence or a premonition because for once, I left the small lamp above the chart table on and decided to lie down on the port bunk, the lee side.

My sleeping bag was damp, and my mattress as inviting as a garden bench in the rain.

The catastrophe has arrived. The long-feared capsizing and my rather eventful awakening. First assessment: the head of my Hydrovane self-steering gear has suffered damage, but it still functions and steers my wounded vessel, which now zigzags between walls of raging water. Yes, the shrouds have loosened under the impact, and the mast has indeed been damaged at the port anchoring point of the shroud. To relieve it and potentially preserve it, I have no choice: I must position the boat in such a way to put the least sideways strain on the mast.

This means I am steering north – the opposite direction to the route I’d been following until now. I curse myself.

Van Den Heede’s Rustler 36 Matmut goosewinged in good conditions in the Southern Ocean

I should have anticipated more, especially since I had a significant lead over the rest of the fleet and should not have stayed parallel to the waves for so long.

What a fool! Now it’s over; I will have to abandon the race. To make matters worse, the depression that has just pummelled me is not willing to let go. I have no way out. I know the rules forbid me from making a phone call – risking immediate disqualification – but I can’t help but grab my satellite phone to reassure my partner. She’s in a meeting, but, thanks to the miracle of technology, she answers on her mobile. I know I am breaking the race rules, but I especially don’t want Odile to learn about my distress and troubles from a third party, a member of the GGR organisation, or worse still, from social media.

I briefly tell her that I am diverting to Puerto Montt in Chile and ask her to contact the local Beneteau dealer so they can best organise my arrival – and my withdrawal from the race.

Considering giving up

I could continue my journey after repairs and compete in the Chichester Class, into which competitors drop if they have made one-stop or received outside assistance while at anchor. I don’t even consider this option for a second. Perhaps, as a beginner during my first circumnavigation, I might have set off from Chile again, but now it’s inconceivable. I would feel like I’m failing, wasting my time. This is my sixth and final solo circumnavigation race and arriving without stopping is my only goal.

Disheartened, I sit at the chart table, open my notebook, and in capital letters, with a blue pen, I write: ‘CAPSIZE! SO THERE IT IS, THE JOURNEY IS OVER’ I no longer maintain my heading, no longer plot my course, and no longer mark any points on my soaked chart.

Van Den Heede completed the 27,000-mile Golden Globe Race in 211 days 23 hours 12 minutes

Time has stopped. What’s the use? I no longer consider myself part of the race and feel like an outsider. I think about selling my boat there and then, getting a flight back home as soon as possible to spend Christmas with my family.

Nevertheless, I start pondering on getting a new mast sent from France and continuing my adventure outside the race. I no longer know what to do. On the edge of the storm, my mind is boiling over. For sure, the mast is damaged, but my margin of safety is still reasonably comfortable. Soon, the wind shifts to the north-west, and the sea gradually calms down.

The situation isn’t ideal, but it allows me to consider some repairs. I prepare my tools and strap on a harness, the kind usually used by mountaineers. I’m no longer in my 20s. Climbing the mast is always perilous at sea, not to mention the descent.

Picture this: a still-choppy sea, swells of 3m or more, an ‘old’ man struggling to climb by sheer arm strength a telegraph pole more than 10m high. I’ve experienced calmer situations. I quickly confirm that the port shroud attachment has cut through the mast downwards like a can opener. The backing plate is torn off. My mast is in a sorry state.

With nothing to lose, I’m going to try to stop further damage by lashing the shroud attachment to secure it from slipping down further.

atmut running before heavy seas. The boat was knocked down at night but survived to complete the Golden Globe Race ahead of all other competitors

I climb up again a second time, the following day, an operation that requires more than two hours of intense effort, with cramps and bruises as guaranteed bonuses because of the wildly swinging motion of the mast and the effort of holding on for dear life. I’m exhausted. I contemplate the most ingenious, or at least, the most effective solution. I need a very strong piece of rope of a few millimetres in diameter. The only piece suitable is the string of my trailing log.

Making repairs

For four days, I strengthen my mast and tighten all the shrouds, spending hours contorting myself, hanging onto a pole that seems to have taken on the role of a windscreen wiper. The 6cm gash at the shroud attachment on the mast is consuming me. But if I can secure the mast sufficiently, I might be able to pass Cape Horn and, at the same time, try to get a little closer to France. And if everything were to collapse despite my repairs, I could still set up a jury rig and reach shelter somewhere on the coast of South America. It’s decided: I will continue!

I don’t really know where I am because it’s been six days since I’ve used my sextant. But it doesn’t bother me at all because where I am, in the middle of the vast Pacific, I have plenty of water to sail through. There’s not an island or a rock in sight. I note in my logbook: ‘Repair completed. Exhausted. No position, no log. Back underway at nearly 6 knots. Great!’

I finally take a sight but mess up the calculations like a novice in celestial navigation. I write, ‘Not very good at maths (the maths teacher!). I’ll take a noon sight tomorrow… if there’s sunshine.’ Nevertheless, I doodle a little smiley face – a smiling Jean-Luc. Another equally fierce depression is expected in 24 hours. Truly, the Pacific doesn’t live up to its name. I can’t wait to get around Cape Horn.

Buy a copy of The Last Seadog from Amazon

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Extract from

Extract from