The Olympic party is now in town, but Jill Dickin Schinas enjoyed a party of a different kind in the Brazilian port of Rio de Janeiro, though it wasn’t all to her liking

Scarcely ruffled by a lazy late afternoon breeze, the sea was an oily pink and orange lake. Two miles to the north, an endless chain of tall, strangely curvaceous grey mountains hovered over a thin band of mist.

The sound of surf breaking on the unseen beach at the foot of these mountains was like the distant roar of motorway traffic and this rumble had accompanied us ceaselessly throughout the day as we drifted south. Our destination now lay less than ten miles ahead.

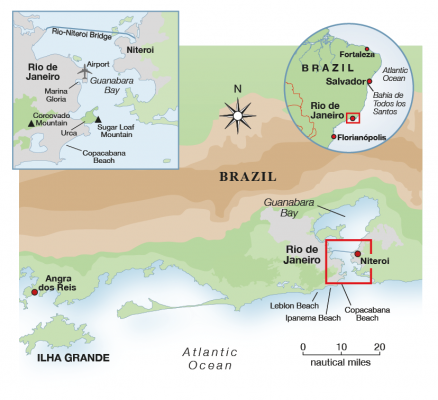

Rio de Janeiro came 1st in the New York Times list of places to visit in 2013. I cannot pretend that this accolade would have stirred us to cross the ocean – after all, Marseille scored 2nd place and Amsterdam was only just outside the top five – but Rio just happened to be on our way as we journeyed between Brazil’s two yachting playgrounds, the Bahia de Todos los Santos to the north and the Ilha Grande. And Rio’s New Year’s Eve celebrations are the most extravagant in the world.

On Mollymawk we made the most of the thunder squalls and eventually arrived outside the harbour in the small hours of the morning. From here the tide took us in hand, sweeping us through the narrow entrance, with its overlooking forts, and into Guanabara Bay.

We turned hard to port, crept along beneath the Sugar Loaf – one of the city’s iconic landmarks – and dropped anchor right there, below the famous cable car. Even at 0400 the town was still bustling and its lights formed an amphitheatre all around us. Meanwhile, looking down upon us from the sky was the statue of the Son of God.

A continual stream of aircraft came thundering overhead, turned at the last moment and then roared over our masthead. The runway seemed to float at the edge of the harbour, just in front of a huge bridge; but at first it looked as if the aircraft, banking again and making their final approach, were set to pass under the bridge.

Later, the water wafting past the boat was strewn with flowers, and among them there were some model boats. Initially we thought that this might be a quaint means of scattering the ashes of some late-lamented person. But the little blue boats proved to be carrying offerings for the Brazilian ‘Queen of the Sea’, Iemanja.

One bore a soggy letter addressed to the goddess asking her blessing through the coming year. Another carried a tacky plastic comb, a scrap of rather slimy soap, a cheap mirror and a small packet of talcum powder.

New Year celebrations

As darkness fell over the city of Rio de Janeiro and the Corcovado mountain vanished beneath O Cristo’s feet, 200 yachts went streaming out of the harbour to watch the fireworks, and we joined the flow. Just around the corner lay the world’s most famous beach, Copacabana. It was already thronged by two million ant-like figures, and anchored off the beach were no fewer than ten huge cruise ships, each bejewelled with glittering lights.

We took up station inside the line of ships and close by a pair of huge tugs. Halfway between us and the shore was a string of 11 large barges carrying 25 tonnes of fireworks said to cost in the region of £5 million.

Shutterstock / Val Thoermer

Rio is, however, best known for its carnival, an event that the local council, with typical Latino modesty, bills as ‘o mais grande espectaculo da tierra’ and ‘o meior festa do mundo’. We were still in the area when this took place and were able to return to the city and check it out. ‘The greatest show on Earth’ it is not – not in my book, anyway – but the second claim is probably well-founded: Rio’s carnival probably is ‘the biggest party in the world’. Several million people all enjoying themselves as only Brazilians know how, with four days and nights of non-stop music, dancing and beer swilling.

Visiting tourists are encouraged to spend at least one evening at the sambódromo, a massive stadium where the ‘Samba Schools’ strut their stuff in sequined satin and feathered finery. This side of Carnival is big business. The larger Samba Schools can produce a procession half a mile long with 5,000 participants, including film stars and celebrities, and they will happily spend £10 million on their efforts. (Yes, you read that correctly: each of the big schools reckons to spend ten million pounds annually.)

Much of this money comes from sponsorship, but the local government also chips in, and – needless to say – they want a return on their investment. Tickets for a seat in the sambadrome start at £70 and go up to about £300.

Fun on the streets

So far as most Cariocas (or residents of Rio) are concerned, the Big Business side of Carnival is irrelevant. They get their fun on the streets and on the beaches. By 1000 there were half a million people on Praia Ipanema, and by midday there were twice that number. Adding all the beaches, we are talking about a belt of sand four miles long and about 100m wide, together with the strip of road and pavement – all with standing room only!

The streets of the city were also thronged, and many were closed to traffic. There were people everywhere. And what were they all doing? They were partying, of course! They were dancing and laughing, and drinking, too – buying their beers from vendors who passed through the crowd, and throwing their empty cans down as fast as the ‘recyclers’ could pick them up. (You can get £1 a kilo for empty aluminium cans in Brazil, and although there’s no government-organised recycling, there are people who derive the greater part of their income from this source. As a result, 87 per cent of cans are recycled as compared with under 50 per cent in the USA.)

Weaving our way along the crowded streets we encountered scores of blocos – down-market carnival floats attended by a cacophonous noise of drumming and trumpeting and pursued by up to 150,000 happy people. Some of the Carnival singers and samba dancers achieve considerable fame, and even when their time has passed their fans still regard them fondly.

One of the youngest performers was a scantily clad 13-year-old, who smiled prettily as her feet moved to the frenetic rhythm of the samba music, but even more popular was a former queen, a 93-year-old who had to hang onto the side of the float as it swayed to and fro. When she gave the crowd a flash of her fishnet stockings there were roars of approval.

Setting of perfection

Rio certainly knows how to throw a good party. But when the show is over what is there to see and do in this city? Parties apart, Rio’s finest feature is its setting. Sailing in and out of the harbour, you are struck by the absolute perfection of the place – and, equally, by the way in which the city has spoiled that perfection.

Famous Ipanema beach. Photo: Shutterstock / R.M. Nunes

The three-pronged bay is hidden behind a wall of rocks and its entrance is adorned with a sprinkling of islets. No doubt the shores of this tropical paradise were once home to Amerindian people who lived idyllic lives in adobe huts and who traversed the placid waters in dug-out canoes.

No matter that they spoilt the perfection of their existence by making war on each other and devouring their enemies; at least they didn’t trash the Garden of Eden. They would be shocked if they could see what has become of the place. As it is their memory lingers on only in local place names, such as Ipanema and Copacabana.

The first Europeans to sail through the cleft between the hills must have been wonder-struck both by the beauty of the place and by its obvious value as a haven. No doubt the subsequent construction of a settlement and its expansion were inevitable, but still you cannot help but think with nostalgia of that pre-Columbine past.

Nowadays a pall of smog often hangs over the bay, a fog of haze spread by the aircraft that roar in and out all day, and by the traffic whizzing around the streets, and also by the ships and fishing boats that head upstream to the commercial port.

And that’s to say nothing of the sewage. It is said that more than 70 per cent of the sewage from the 12 million inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro flows into the bay untreated.

Once you have taken up residence in the bay you are apt to be less conscious of the natural splendour of the place and more aware of the immediate surroundings. A berth in the Marina Gloria puts you right alongside the airport – with all that entails – and right in among the sewage and flotsam. A walk through the adjacent park or the nearby streets is not particularly inspiring either. “How do they manage to sell it as one of the greatest places on Earth?” asked another foreign yachtsman, having spent all day dragging around the town. “Ah, yes,” he then answered himself: “Aerial photography.”

He’s right: all the postcards of Rio are aerial views. But you don’t actually have to take a flight to look down on the bay – join The Redeemer on that hill top behind the city. Most people make the journey aloft in a funicular railway and the entrance fee is included in the fare for the train, but even if you travel by that means you still have to join an hour-long queue before gaining admission to the hill.

The greatest, the best and the number one place to see before you die? No, I don’t think so – not from the point of view of a cruising sailor for whom the whole world is an oyster stuffed with pearls. As far as I can gather, the New York Times placed it 1st on their list largely because Brazil was going to be hosting the World Cup. And now the city is about to welcome the Olympics Games.

Rio may not be worthy of its top-ranking position, but it is still pretty special, and for anyone who happens to be passing by – between Cape Town and the Caribbean, for example, or on the way south to Patagonia – the city is well worth a week’s stopover.

How’s the water?

Rio’s water quality and, in particular, that of Guanabara Bay, where the Olympic sailing will be raced, has been hugely controversial – and quite rightly so. ‘Chronically contaminated’ is how European and North American health experts have described the vast lagoon that once was home not only to the Amerindian people, but also to birds and fish and even to whales.

Even in the 1970s the great bight of water above the Rio-Niteroi bridge was still lined by mangrove swamps and sandy white beaches, but the mangroves have since been destroyed by an oil spill and the beaches lie hidden beneath refuse.

Guanabara receives much of the effluent not only from the sprawling city of Rio with its docks, oil terminal and slums, but also from the town of Niteroi, on the opposite shore. And since the pond is almost landlocked it’s no wonder that it has become a cesspool.

The nearer you get to the harbour entrance, the greater the exchange of water and the less obvious the pollution, but the flotsam and the poisons do still snag in the nooks and crannies – and unfortunately the Olympic sailing fleet will be based in one such back bay, in the Marina Gloria. To be frank, this place stinks.

Urca, one of the cleaner places. Photo: Shutterstock / Iuliia Timofeeva

Floating rubbish piles up among the jetties and on the nearby beach, and pollution levels are such that notices generally place it out of bounds to swimmers. In the light of much negative international publicity, the city is building an outfall pipe to carry the sewage further from sight; but in this case, out of sight is certainly not out of mind.

After examining data relating to water samples take from the harbour, experts have said that athletes at all water venues will have ‘a 99 per cent chance of infection if they ingest just three teaspoons of water’ – although whether a person falls ill will depend on their level of immunity.

While the sailors race inside the bay, other Olympic competitors will be doing their stuff in the waters off the Copacabana beach. Since it lies outside the harbour, on the city’s seaward face, you might imagine this place would be relatively clean – but it isn’t.

The hills behind the town are home to some of the city’s poorest inhabitants – their sprawling favelas are the ones that feature in Disney’s recent cartoon in which the blue parrots make their escape. The sewage from this area doesn’t even travel through a pipe to reach the sea; it just rolls down the slope. A fellow sailor taking a dip on the beach gave it up after the third condom washed past his nose.

Is there any corner free from sordid sights? Yes, there is; there’s Urca. Presumably this place gets a good flushing by the tide, because the beach below the Sugar Loaf is reckoned to be the cleanest in the whole bay. The only flotsam that we saw while we were anchored here was flowers and Iemanja’s ‘toy’ boats. Whether the place is completely free from E-Coli and other viruses I don’t know.

All I will say is we swam here and lived.

So where should you go?

Few yachtsmen spend a lot of time in Rio. It’s not the sort of place that pulls the visitor in and tempts them to spend a season hanging out. However, there is just such a place hardly a day’s sail to the south.

Ilha Grande. Photo: Shutterstock / DC_Aperture

The Bay of Ilha Grande is a huge cruising ground consisting of a ‘Big Island’ which backs onto a wonderful collection of coves, inlets and little islets. There are various small towns and villages on the adjacent mainland, and Ilha Grande itself is covered in pristine forest. Numerous trails lead to the island’s peaks or to beaches on the windward shore, and a rambler might encounter iguanas and snakes and is almost guaranteed to sight a troop of saguin, or marmoset – the evil-faced monkeys that feature in the Rio cartoon.

There are also cougars, jaguarundis (a very much smaller cat),and even jaguars lurking in the depths of the forest. From a boat you can hear the bragging calls of howler monkeys and if you go to the right beach (or the wrong beach?) you might meet crocodiles.

Shutterstock / DC_Aperture

Pretty much the only thing that the Ilha Grande area lacks is wind. All the same, we managed to spend three months here and to visit more than 30 anchorages without motoring once.

Although there are always half a dozen tankers anchored in the lee of the island the area seems to be relatively clean – thus far there has been no major oil spill – and there is none of the plastic and sewage pollution you see everywhere in Rio.

What effect the nuclear power plant at the back of the bay might be having on the water is something you might prefer to overlook.

Jill Dickin Schinas has been sailing all her life. She made her first ocean passage at 19 and has been living aboard boats ever since. In 1989 she and her husband-to-be set off round the world. She paints and writes features and books.

www.yachtmollymawk.com