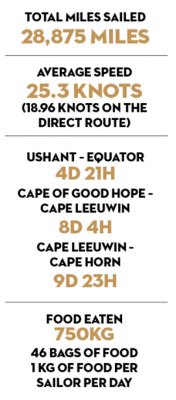

As two round the world record bids turned the Jules Verne round the world record into a race, the giant trimaran Spindrift 2 streaked home at an average of over 25 knots. But it was not enough, writes Elaine Bunting

It was one of the fastest ever laps of the planet under sail, but the crew of Spindrift found their race home interminable. Dona Bertarelli, the billionaire owner of the 130ft maxi catamaran, on board as part of the crew of 12, described the stretch from Cape Horn to the finish at Ushant as an “ascent . . . long, laborious, and it felt like time was standing still.”

After 29,000 miles of speed sailing, hunting the weather and often riding faster than the fronts they were seeking, Spindrift coasted comparatively sedately across the line that marks the start and finish of the non-stop round the world record. Their time of 47d 10h meant the Jules Verne Trophy eluded them by two days.

But though they failed to break the record, two attempts by two very different crews has rekindled interest in one of sailing’s most exciting challenges.

The record attempts began in strong northerlies on 22 November. Dona Bertarelli had been long planning this with her partner, French sailor Yann Guichard. Spindrift 2 was formerly Banque Populaire V, the 130ft trimaran that captured the record in 2012 under Loïck Peyron.

A good bet, then, for an improvement on the record time. The Spindrift team estimated that with favourable weather and a bit of luck there was as much as a day to shave from Banque Populaire’s time of 45d 13h.

Guichard, an experienced former Olympic and ocean sailor, had a view that the crew should contain a range of specialists: helmsmen (including Bertarelli), navigator, bowman, trimmers and so on – 12 in total.

Stamm and Joyon

Their rival for the record, the redoubtable Francis Joyon, one of France’s most famous solo sailors and a man famous for doing things his own way, had a contrasting approach.

Joyon also had been planning an attempt on the Jules Verne and selected a smaller trimaran and a smaller crew. He opted for the 105ft IDEC Sport (formerly record holder Groupama 3) and hand-picked a crew of six all-rounders, skippers in their own right, a band that included such names as Bernard Stamm and Roland Jourdain.

Photo Jean Marie Liot / DPPI / IDEC

Independently the two crews picked the same weather system on which to depart, sprinting over the line only two hours part. For the first time, and without planning, the Jules Verne Trophy was a proper boat-on-boat race.

Sprinting out of the traps

Spindrift 2 came out of the traps the quicker of the two and in strong following winds scorched south to the Equator in a record time of 4d 21h. It was fast, furious and soaking, and the crews said that it was the wettest they had ever been.

A slower spell in the South Atlantic followed, but they were always just ahead of Joyon’s crew until Guichard’s team picked up the ‘express train’: their first opportunity to hook into a Southern Ocean low pressure system.

One might think that the disparity in size and power of these two boats would make it impossible for the smaller of the two to be the faster round the world. But there is a catch to being big and fast in the Southern Ocean, and as long as IDEC Sport could catch the same train east there was every hope they could match each other to Cape Horn.

The conundrum for any Jules Verne attempt is that it will be won or lost in the Atlantic, out or back. These are the only sections of the circumnavigation where large enough gains can be made.

Giant trimarans such as Spindrift are quick enough to make those gains provided they get the weather breaks, but they are arguably too large for the Southern Ocean ‘train carriage’ lows. Here, they are too fast, as Spindrift’s weather router and forecaster, Jean-Yves Bernot, explains.

“We have a big problem with these boats,” he says. “They are too fast for the Southern Ocean, particularly with [the weather] we got in the Indian Ocean. We would be faster than the weather system, we would overtake it and then were stopped waiting for the low to come back.”

Work of the weather routers

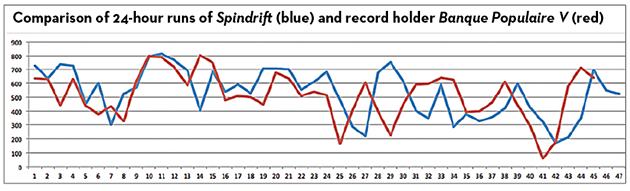

The ideal position is to be east of a cold front at a good angle, in more stable winds and more regular seas that enable surfing. But with boats like Spindrift and IDEC, able to sail at mean speeds of 35-38 knots, keeping in this dialled in position for long is impossible: the weather systems themselves are moving at only 25 knots. While the yachts can make huge daily runs, sometimes in excess of 600 miles, before long they will get out of synch.

The work of the weather routers is critical to these records. Working with IDEC Sport was Marcel Van Triest. These were the invisible crew, on land but always on call, day and night, unable to leave home without phone and computer.

For Bernot, each day revolved around preparing two forecasts, with detailed correspondence by email, as well as talking by phone to Guichard or to Spindrift’s navigator, Erwan Israel. There are many considerations to weigh up, by no means simply speed. Sea state is frequently as important, or more so, as are the number and pace of sail changes required.

“We had a lot of conversations [about that],” explains Bernot. “For them it was important that when there was a sail change, it was not for half an hour. We’d ask: ‘What if we alter course some degrees to make it easier?’ Fine-tuning is important on these vessels – it’s not sending a weather bulletin in the morning and saying ‘Good luck, guys’. “

Within sight of each other

Despite IDEC being 800 miles behind and taking a very different course, the two boats almost converged mid-December in the Southern Pacific after 15,000 miles of sailing. For part of a day they were in sight of each other.

As the two crews crossed the Southern Pacific Ocean a huge high pressure area blocked their paths and presented a dilemma. The only options were to go round on a long route to the north, or dip deep south on a shorter route at risk of encounters with ice. Because the southern option could be tempting, the two weather routers made an unprecedented gentleman’s agreement.

“The idea of sending the guys down there would stop us from sleeping,” says Jean-Yves Bernot. “Marcel [van Triest] called me to ask my opinion and we said to each other ‘What are you doing? Are you diving south or not?’ Because if one does there would be the temptation for the other to do it too and as routers we said we didn’t want to risk it.

“We must not forget that this is a sport. That means that we want to know who is best when everyone is playing by the same rules.”

After a month at sea, Spindrift rounded Cape Horn ahead on 23 December, with 15 knots of wind and a flat sea. “Honestly, it was just fantastic,” Yann Guichard said. It was his first time round Cape Horn; his first circumnavigation. “Dona spoke with the lighthouse keeper; it was really a nice moment. Everyone was awake and on deck.”

“Now that’s done, it’s the weather that will decide,” he said. The weather did decide, and lay an obstacle course of light winds and ridges ahead of them. Their course, and IDEC’s behind was, as they described it, like needlework: ‘Cross stitch, daisy stitch, eyelet, feather stitch, blanket stitch, running stitch, chain stitch . . .’

Split at the Falklands

The two yachts split either side of the Falkland Islands, working hard to match the record time. Incredibly, on 26 December, while off the coast of Argentina at 43°N, IDEC’s crew reported a huge iceberg just over a mile away, the largest Bernard Stamm had ever seen, complete with cliffs and a light blue hue, “a huge wall of ice”.

“This is a matter that worries us all at the moment. We are pushing things too far with the climate. We really need to be careful,” said Francis Joyon. “It’s important for us to be here to bear witness to what is happening.”

Spindrift passed the Equator 1d 10h behind the record. It seemed possible to beat the target, but as the days counted down the route ahead began to close off.

The Azores High was huge. The two crews had some hopes that a cold front would cut a path through it, but this shortcut never materialised and they were forced to go the long way round. On these records, heavy weather is rarely the problem because even in the strongest winds the boats can average 25 knots. If the course is along the rhumb line everyone is happy. It is the light winds that make or break such voyages. “The high pressures are the real boss on the record; they decide how your course should be set,” observes Bernot.

Time standing still

It was, as Dona Bertarelli later said, as if time were standing still. After six weeks at sea, driving as hard as the boats and crews could manage, Spindrift and later IDEC finished out of time. Neither voyage, safely concluded, could be termed a failure, but they weren’t the successes they’d hoped for either. This is going to be a tough, lengthy, expensive record to crack.

Whether Joyon and his crew come back to try again next year remains to be seen. The rumour is that Spindrift’s crew will attempt it again, though not necessarily with Bertarelli on board.

But with such small margins to be gained now, a day or less if all goes swimmingly, could the record ever be reduced much below 44 days in future? Jean-Yves Bernot thinks it could, and the answer is not, as you might expect, all about improved yacht design. In his view, there is a lot to be done in terms of understanding how to navigate varying sea states.

“Waves are very important; they can make a 20 per cent difference between boat speed depending on sea state. The forecast information is pretty good for the wind, but for the waves it is not that accurate and we don’t know very accurately the impact on boat speed.”

Bernot believes there is a lot more testing and interpolating that can be done, and that this is a significant area of development. “A trimaran is complicated. We know how high waves are, but not the period and we need to know more about cross seas and how steep they are. It is more complicated than we can extract at the moment, but that will change. We are still at the stage of trying to define what we want from the data.

“First we need to try to make tests and understand how the speed depends on sea state. Getting data has not been properly done, it will help improve how boats are steered and for designers it’s a big chance in the next three or five years.”

Sooner or later this record is going to fall, and until a future giant multihull is built, Spindrift is the likeliest tool for the job. Not this time. But maybe next winter.

Who is Dona Bertarelli?

by James Boyd

Her elder brother, Ernesto, is famed for his America’s Cup victories, but Dona Bertarelli is now rivalling him when it comes to great endeavour in yachting – the Jules Verne Trophy attempt makes the 47-year-old the fastest woman round the world under sail.

The Bertarellis have sailed all their lives, initially cruising in the Mediterranean. Ernesto raced multihulls on Lake Geneva in the 1990s and Dona followed this same route by setting up the all-female Lady Cat campaign in late 2006 to compete on the Swiss D35 one-design catamaran circuit. Three years later with Dona at the helm, the fuchsia-coloured Lady Cat won Switzerland’s top sailing event, the Bol d’Or Mirabaud, with a crew of seven including two men.

Ernesto and Dona come from the Italian Bertarelli family, three generations of which developed the pharmaceuticals and biotech company Serono, best known for developing the first fertility drugs – one of which helped create the first test tube baby in 1978. Their father Fabio relocated Serono from Italy to Switzerland in the mid-1970s. From 1992-97 Dona served as an executive director, before leaving in 1998 to raise her two children.

The Bertarelli family sold their stake in Serono for £4.6 billion and Dona now owns the Grand Hotel Park in Gstaad, Five Seas Hotel in Cannes and Country Club Geneva. She also co-chairs the Bertarelli Foundation, set up in honour of her late father, which focuses on marine conservation and life science research.

In 2011, with her partner, former Olympic Tornado sailor Yann Guichard, Bertarelli established Spindrift Racing, initially to compete on the MOD70 one-design trimaran circuit. In 2013 they made their biggest acquisition, the 130ft Spindrift 2.

What drives Dona to do a Jules Verne Trophy attempt? “I think it’s the passion – you need to be passionate, you need to love sport, to love sailing and the sea. Yann and I have built this stable [Spindrift Racing] together and I want to be part of it completely.”