A secondary low can be hard to spot, even in these days of good weather information, says meteorologist Chris Tibbs. And it can be dangerous

Some years ago while racing somewhere south of the Kerguelen Islands in the Southern Ocean, an area well known for cyclogenesis (where lows are born or develop), we went from running to beating in a short space of time. With sea water at about 6°C and 40 knots of wind, this was not a very pleasant experience.

In those days our forecasting was limited to occasional weatherfax pictures that depended on how clear a signal we could get on the SSB. The charts did not show any headwinds at all and we should have been barrelling along under spinnaker.

What had caught us out was the rapid development of a secondary low that formed and deepened south of the Kerguelens. This slowed us up considerably, but secondaries are a feature that needs to be taken into account when sailing in mid or high latitudes.

In the days of the heavy IOR maxis the further south you dared to go, the stronger the wind and the faster you went, until ice and the cold made it unsafe, or you got on the wrong side of a low. All quite reasonable and by tracking the progress of lows it should be easy to stay on the right side.

However, in this case what was not well forecast was the development of a secondary low. These form within the flow of another low. Initially they are of a higher central pressure, but they can deepen rapidly and produce some unpleasant weather.

Although the lows nowadays will be reasonably well forecast, because of their rapid development it is easy to miss them until it’s too late.

Limited information offshore

Fast forward a few years and our forecasting models are very much better and freely available, but that said, the weather can still change rapidly and once you are offshore the information available is severely limited by your communications.

At the end of April we had a rather unusual snowfall in the UK, which made the news – unusual in that it was late in the year – but what caught my eye was that it came from a secondary low that was hardly noticeable on synoptic charts until it deepened and moved over the UK all in under 24 hours.

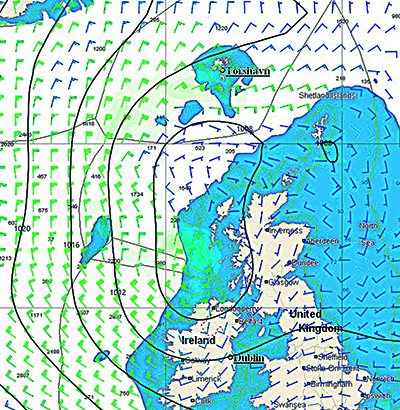

If you follow its development using GRIB files (see below) you can see initially there was a widening of the isobars to the north of Ireland. There was not a great deal to get excited about, although near Rockall a north-westerly of 25 knots was already blowing.

Initially you see a widening of isobars north of Ireland

If you scroll on six hours a new low has formed and there is circulation south of the Outer Hebrides. The interesting point about this is that from a synoptic chart you would have probably been expecting a north-westerly wind not an easterly.

Six hours later there is a tight little low over Tiree with gale force winds on the south-west side of the low – the side away from the parent low, which has moved away over Scandinavia.

Twelve hours later the low has passed over southern Scotland dumping a load of snow before moving into the North Sea and away.

Speed of the secondary low

Although forecast, it was the speed that it deepened and became a significant feature that made the secondary low something worth watching. This is particularly important when offshore with restricted access to forecasts and, although there are limitations to GRIB files, they are extremely useful as you can scroll through in three-hour time steps, making it easier to see how systems are developing, rather than having to rely on synoptic charts with a 12- or 24-hour time step.

Pointers for secondary lows

- They develop within the existing circulation of a low pressure system.

- The first pointer is the widening of the isobars, usually near a cold front or trough. There may be a small wave on the front. A secondary may also develop near the triple point where the cold front, warm front and occluded front meet.

- The wind will increase on the side away from the parent low, but will also reduce between the parent low and the new secondary low.

- There can be rapid development of the new low to a lower central pressure than the parent. This is most likely to happen when the secondary low is greater than 600 miles from the parent.

- The low will rotate around the parent low.

- On satellite pictures the first indication will be a comma cloud over the new low.

Chris Tibbs is a meteorologist and weather router, as well as a professional sailor and navigator, forecasting for Olympic teams and the ARC rally. He is currently on his own circumnavigation with his wife, Helen. His series of Weather Briefings can be seen here

See also:

Chris Tibbs prepares his own boat for an Atlantic crossing

The best route for an Atlantic crossing

Taking the northerly route across the Atlantic

Offshore weather planning: options for receiving weather data at sea

as well as Chris Tibbs’s series of Weather Briefings