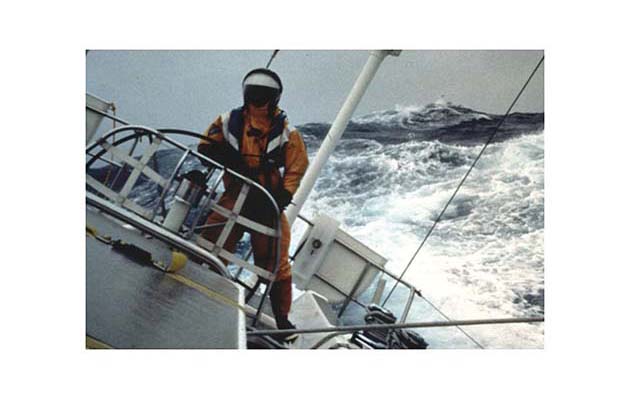

Tom Cunliffe introduces an extract from Uphill All the Way by Alan Sears, recounting a fearsome Southern Ocean leg of the 1996-97 BT Challenge race aboard Toshiba.

Most accounts of grim conditions in the Southern Ocean are written by skippers of race boats or owners of smaller yachts engaged in high adventure, writes Tom Cunliffe. Uphill all the Way by Alan Sears is different.

When he signed on Toshiba with the BT Global Challenge for the 1996-97 race he was a music teacher who had been, amongst other things, a cycling champion, a violin maker and a groundsman. One thing he was not was a professional sailor.

His take on events in the storm-lashed seas centres around his shipmates being beaten black and blue by the extreme motion of a big yacht racing upwind as hard as she can go. Those of us who have avoided this experience tend not to think about the hammering that bodies take as these powerful, unbreakable boats leap from wave crests into deep holes in the ocean.

Here, we have it spelled out. From the start, Sears is suffering from a painful knee injury sustained in the previous chapter as he was washed off the wheel.

We join Toshiba and her bold crew far south with ice threatening and Cape Town an impossibly long way ahead.

Deep in the Southern Ocean, the weather continued as before. On the wheel one day, it occurred to me that the wind had not dropped below 38 knots for the past hour.

‘So it is a gale,’ I thought, ‘and we no longer think anything of it.’ Ludicrously, we had reached the point where 40 knots seemed reasonably comfortable, just so long as we had approached it by coming down from 50!

As night fell, this particular gale blew into a storm, with the wind running at a constant 45 knots, but with the sea relatively (and only relatively) flat for that amount of wind. This meant that Toshiba would crank right up to about 8.5 knots, and then we would hit a `backless wonder’ or a real corkscrew.

A wave with no back gives the boat nothing to slide down; you just take off from the crest and plunge way, way down, into the trough beyond. The corkscrews pick the back of the boat up as they pass underneath, twist you round and throw you down into the trough – the effect is much the same.

I felt in imminent danger of serious personal injury for every minute I was on the helm during all this. All we could see, even granted an occasional flicker of moonlight between the sullen clouds, was a dark grey horizon with a black sea billowing beneath it.

When the horizon rose up rapidly, so that most of what we were looking at turned black, we braced ourselves, gritted our teeth and hung on.

Half the time nothing happened. Toshiba would roll over the top of the wave, twist, and try to head off the wind. I would steer to correct that, there would be some spray, and we would slide down the other side, untroubled and unharmed.

Then, every so often, we would be launched with enormous propulsion, like a powerful steeple-chaser taking off at a truly huge fence, and we would plunge down, free-falling, until Tosh buried her bows with an almighty crash. If steering, you would be flung against the wheel while, simultaneously, it would be wrenched round with more force than you could possibly hope to counteract.

The instinctive reaction was to hang on for grim death or should that be dear life? If you did that, the wheel swept your hand into the narrow gap where the rim passes the cockpit seat. At best that was very painful, at worst things got broken.

Simultaneously a huge mass of water would slam into your head, shoulders and chest, knocking you backwards. It was blinding.

Even with a helmet or goggles you cannot see through solid water. Walls of white foam rushing by above the sides of the cockpit would add to the flood swirling round your feet; there was just water everywhere.

Half standing, re-bracing your legs, you would drag the wheel back because already the next black monster would be rushing towards you, climbing higher and higher on the bow. ‘What a nightmare!’ was Kobus’s somewhat succinct summing up of the situation.

The change down from staysail to storm staysail was one of the worst tasks. It always took place in fearsome conditions, and meant working in the middle of the foredeck, with very little around to hold on to.

Struggling with the change one night, Ben’s watch were practically swept off the deck by the biggest crash any of us ever heard on Tosh. Ange, Ben and Kiki all sustained minor injuries but Haydon, not long over a nasty back problem, was in serious trouble.

Unable to move, let alone get himself back to the relative safety of the cockpit, he was clearly in agony, and it looked as though Spike’s worst medical nightmare had come true; we thought he had broken his leg.

The prospect of getting a badly injured person off the foredeck in these conditions does not really bear thinking about, but in fact we had thought about it, in advance. The first part of the plan – to run downwind, keeping the boat stable and the deck relatively flat – was easy.

After that there was nothing for it except to drag Haydon back, as gently as possible, whilst trying to support his damaged leg. His trip down the companionway steps was a miracle of teamwork and compassion, and we finally laid him on a pair of coffin bunk mattresses on the floor by the chart table.

‘Are you particularly attached to that drysuit?’ asked Simon, preparing to cut the fabric away. ‘I am, as it happens,’ replied Haydon through rather gritted teeth. So we inched his boot off and painstakingly got him out of his drysuit, and slowly, piece by piece, removed enough of his kit so that Spike could examine his leg.

Alan Sears celebrates his birthday in the Southern Ocean.

Rounding the Kerguelen Islands

It didn’t look good. A possible fracture of the shin bone was only half the story; it looked as though Haydon might have broken his femur as well.

We managed, with the aid of painkillers and some improvised padding, to get Haydon secure in his bunk, and considered our options. There were not very many and, depending on Haydon’s condition over the next 24 hours, pressing on was the only one immediately available.

Grateful as I was to have escaped so lightly, that still did not ease my own problem which was that every time I went on to the foredeck, I hurt my knee badly again. It simply was not possible to stop yourself being flung around, and every wrench crippled me anew.

I upped the painkillers and continued to swear flatly, vehemently, viciously and repeatedly every time it happened. When we finally rounded the Kerguelen Islands waypoint after just 24 days at sea, everyone had really had enough. Even Spike remarked to me that he was counting down the days!

As if to herald the approach of better times we witnessed a superb sunrise as the cloud dispersed, but later that day the generator exhaust failed terminally. We had barely enough fuel to charge our flagging batteries and keep the water maker operational using the main engine, and there were still 2,000 miles to go to Cape Town.

Nevertheless a certain euphoria set in and things did gradually get better. We headed up north, on course for Cape Town, and sea and air temperatures rose from freezing to tolerable.

The risks of icebergs receded, the wind no longer roared up above 50 knots with frightening regularity, and we began to look forward to some sunshine. Only a few days after his terrible accident Haydon struggled up and began making cups of tea and monitoring the chart table instruments, while still barely able to drag himself about the boat.

By some miracle his injuries were restricted to a compression fracture of his shin bone and an ugly swelling the size of a large melon on his thigh. We were almost out of it, but not quite.

The change to the storm staysail caught us once again, this time on our watch. Geoff banged a previously damaged arm and bruised himself badly being flung against the winch he was working, Mark’s hand was dragged through the side netting, put in place to stop sails being swept overboard under the lifelines, and Justin banged his head.

I was practically winded by a wave which hit me square on the back, and I hurt all the bits which hurt before plus a few new ones. More 60 knot gusts followed, and in one of them we achieved one of Simon’s great ambitions: we broke the starboard head falling off a wave!

A good two seconds ‘air-time’ was followed by an unbelievable rig-shaking, hull-quaking CRA-A-A-A-A-SH and the porcelain lavatory pan cracked wide open from base to rim.

Full steam ahead for Africa

Looking back we were able to pinpoint, to the day, our leaving the Southern Ocean behind. We looked behind us and saw the lowering clouds of the last of those massive weather systems, and from that day on things became reasonable again.

Now we were left with the small matter of trying to win a yacht race. The generator exhaust was still proving an on-off affair as Geoff and Haydon, working in spite of his leg, struggled to bond bits of old tin can and anything else they could find around the offending junction.

That meant saving on electricity by being mean with the lights, as well as using as little water as possible. The deck light had given up, the home-made spotlight was on its last bulb, and we were nearly out of torch batteries.

We had no sugar, and were low on cheese, butter and bread mix. Toilet paper was being strictly rationed, and breakfast was reduced to cereals only, but we were still able to put together a respectable chilli and rice followed by apple crumble and custard for supper.

The wind filled in, and once again we gave chase to Concert and Group 4, whose battle for the lead was, to our chagrin, taking place a few miles ahead of us. At one point Simon managed a top boat speed of 21.5 knots under a poled out No 1 yankee, and then, before anyone else could threaten that speed, decided that we needed to change down!

Kobus then proceeded to clock 18.3 knots with the No 2 yankee up, the staysail and the first reef in the main, which must be some sort of fleet record.

The Agulhas current, which we expected to sweep us around the tip of Africa, failed to materialise, but just after 9am on Tuesday 8 April, after 37 days at sea, a cry of ‘Land Ho!’ from on deck, brought us all up to gaze at an uneven blur at the distant edge of the sea. ‘Is that all?’ someone said jocularly.

‘That’s Africa,’ I said, ‘and it’s the first time I’ve ever seen it.’