Master the arts of downwind passagemaking and some of the world’s most beautiful cruising grounds open up. Elaine Bunting went to Fiji to help prepare and film a 12-part series on the skills you need for bluewater sailing

The Russian owner of a superyacht came ashore at the Fijian island of Wadigi and asked the owner, Tracey Johnston, how much she wanted for it. “It’s not for sale,” she told him. “No, how much do you want?” he insisted.

The Russian owner of a superyacht came ashore at the Fijian island of Wadigi and asked the owner, Tracey Johnston, how much she wanted for it. “It’s not for sale,” she told him. “No, how much do you want?” he insisted.

But Wadigi wasn’t for sale, not at any price, and as soon as you land on the island you can understand the conversation from both sides: why the Russian wanted to buy; why Tracey didn’t care to sell.

Wadigi is where Tracey and her husband, Jim, run a small and very beautiful island hotel, and she tells us this story as she leads us to the top of her island to shoot the final footage for our new Bluewater Sailing Techniques series, which we launch in print and online this month. The island overlooks a narrow channel and this was a perfect vantage point to see the yacht Skyelark of London reaching across between two dazzling turquoise-coloured reefs.

With palm trees and long beaches, empty bays and hundreds of quiet islands, Fiji is a tropical dreamscape. The whole of the south Pacific, in its vast half-a-globe entirety, is filled with islands so beautiful you cannot quite believe you’re lucky enough to be there.

But we were there: me, IPC Media’s creative director, Brett Lewis, cameraman Mike Deppe and Jonathan Reynolds, an insurance claims specialist representing our sponsors, Pantaenius. It was at the suggestion of Pantaenius that we came to the Pacific. When we proposed a bluewater series they said: go there; this is where yachts are heading now. Happy to oblige.

We planned to prepare and film a 12-part Bluewater Sailing Techniques series, with the help of Dan and Em Bower and their yacht Skyelark. Dan would be writing the features, all of which can be foune HERE.

I’ve cruised among the Pacific islands several times before, on passages from the Marquesas to Tahiti and onwards to Tonga, and have always considered it to be the finest sailing I have ever done. Simply put, the Pacific is magic.

Most yachtsmen do not get there. They say they plan to, but the Panama Canal is a portcullis gateway, a commitment too far. Once through, you are almost certainly committed to sailing round the world and so faced with a series of ocean passages to equal or exceed a transatlantic crossing.

This immensity has kept much of the Pacific remote, and it remains in my mind – and that of most others who have sailed there – a Holy Grail of cruising. What we went there to do was to illustrate the passagemaking and pilotage skills that will set sailors up for crossing any ocean safely and comfortably, and add on to that a few of the extra arts to use, and enjoy, among the coral atolls of the Pacific.

Meeting Dan and Em Bower, Bluewater authors

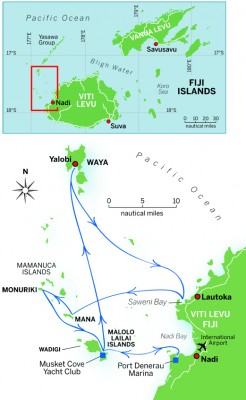

We joined Skyelark at Port Denerau Marina, which lies a few miles from the international airport in Nadi. Here we met Dan and Em Bower, who had cruised from the UK to Fiji in the World ARC rally and recently left it so that they could sail to Australia and continue onwards in their own time.

Dan and Em, both full-time professional skippers, have logged several hundred thousand miles. They usually work with charter guests of varying expertise, so were ideal people to demonstrate the skills needed for tradewinds ocean voyaging.

Port Denerau is a big, modern marina surrounded by a golf course, water park, hotels and a shopping mall; great, perhaps, if you’ve had months among desert islands, but not somewhere that felt truly Fijian. So we left and motored to the island of Mololo Lalai and Musket Cove Yacht Club.

The moorings and open-fronted, palm-thatched ‘clubhouse’ bar is a congregating point for long-distance yachtsmen, and the anchorage has been famous among round the world cruisers ever since it was set up in 1976 by an Australian, Dick Smith.

Our first few days were spent sailing out of Musket Cove practising sailing wing and wing with poled-out headsail and main – the standard, no-nonsense rig for downwind ocean voyaging – and trying some man overboard routines. With that done, we set sail for a taste of out-island Fiji.

The Yasawa group is a sparsely populated chain of hilly islands to the north-west of Viti Levu. The first European to sail through them was Captain William Bligh in 1789 who, with a handful of loyal crew, had been set adrift in an open boat without charts or compass following the mutiny on HMS Bounty. They tried to make a safe landing.

Bligh had previously fled the island of Tofua when one of his crew was stoned to death by natives and feared a hostile reception at Yasawa. He was right: they were chased by cannibals in what is now known as Bligh Water and had to continue westward. They finally made landfall at Timor after an incredible 3,600-mile voyage.

So life in the islands of Fiji barely changed until the 19th Century and was only charted by a US expedition in 1840. Even today some of the outer islands have few visitors other than yachtsmen.

We sailed along the western coast of Waya and anchored as the sun set off the village of Yalobi, a community of some 150 people sheltering beneath a high ridge of hills. During the night, the wind went very light and at times we were lying beam on to a slight scend that sent us rolling uncomfortably. In the morning we decided it was the perfect opportunity to demonstrate how to use a tender to lay a kedge anchor and hold the yacht bows to the swell.

No sooner had we started preparing than, sure enough, a breeze ruffled the bay and Skyelark swung into wind and sea. The forecast was for light winds for the next few days so we carried on, videoing Dan laying out the kedge astern. We attached a tripping line to the anchor and paid it out, but at some point later on the buoy at the end of the line came loose and floated away. Later that was to be an inconvenience that could have been a real problem.

After that, we went ashore. Island life in Yalobi is simple. The villagers live a barefoot life, mainly in small, tin-roofed houses with only one room, where the living quarters are separated from the sleeping area by a curtain. Cooking is done on a raised platform outside and water is taken from standpipes. It is a subsistence economy: the villagers grow fruit and vegetables such as kasava, plantain, mango and bananas in their gardens, travelling by boat on Fridays to Viti Levu to sell any surplus.

Sailor’s aid

Ironically enough, the first person we met was an Australian, Carolyn Mowbray who, with her husband, Tony, has lived in Yalobi on and off for the past three years. Tony is a round the world sailor who first visited Waya three years ago in his yacht, Commitment, found the village so friendly and beautiful that he decided to return and now lives here for much of the year. The Mowbrays have helped organise funding and practical projects for the village, and that day Tony was completing a two-year scheme to install solar power in the village school.

Carolyn introduced us to Atu, a local fisherman, who took us hunting for octopus among the reefs. As we paddled along, I asked him how he knew where he could find them hiding, and he merely noted that they are “very clever” and cover the entrances to their hiding holes with fine stones or sand. Atu was rarely fooled, however, and prodded them out with a fine metal rod, before thrashing them to release the ink and kill them off. After a couple more hours of bashing to tenderise the meat back at home, he cooked them with plantain and coconut cream. It was delicious.

Tony had arranged for us to take part in a traditional Fijian sevu sevu ceremony, where we would be welcomed to the village by the chief and elders, drink kava with them and dance. The ritual is more than merely a tourist gesture. Another settler we met several days later told us that only eight per cent of Fiji is privately owned and that landing on an island without getting ceremonial permission, even if it is uninhabited, is a serious breach of etiquette.

Tony and Carolyn suggested that we might like to have a meal with a local family, and that by paying them ten Fiji dollars a head (about €3) it would help one of the poorer groups. So she arranged for us to have dinner with Andi and her mother-in-law, Taisita.

Andi’s husband Tom died last year from liver cancer at the age of 42, leaving her to care for her son, five-year-old Tom junior. She lives with Taisita in a one-room house. Unlike some of their neighbours, they had a sofa and a raised bed, on which we were immediately offered seats.

As it grew dark they lit a paraffin lamp and we all sat together on the floor while they brought out bowls of plantain, kasava, sea grapes and tuna, stewed mutton and curried papaya, a feast of special dishes. Andi’s father, Tui, joined in and answered our questions about the way of life on Waya and on the big island, and lamented the problem of addiction to kava that he said blights many Fijian communities.

As we were making our way back to the beach we could see the tops of the palms blowing wildly. A full moon was lighting up the bay and it was clear right away that the wind was up and driving a short chop into the bay. Skyelark was lying off a lee shore, with a reef not far astern. We needed get back on board and leave, sharpish.

Getting out of trouble

The six of us got back in two wet dinghy trips. Clambering on board from alongside required careful timing: Skyelark was hobbyhorsing enthusiastically in the swell. The problem now was that we were lying to both bower anchor and kedge, so the stern anchor had to be retrieved (or, if not, buoyed and left behind) before we could leave.

The tripping line, minus its buoy, had sunk so Dan and Jonathan drove out to it in the moonlight pulling along the rode. When over the top of the anchor, Jonathan gave a huge heave and muscled it out. There was no safe opportunity to get the outboard off the dinghy in the swell and darkness; we just had to go. We weighed anchor, slowly motoring ahead as the windlass wound back in the 80m of chain we had payed out and we were off.

Our bail-out plan was to motor to windward through the night back to Viti Levu and a safe, protected bay behind a line of mangroves. By the time we arrived at about 0200 the wind had died again.

Contained within an outer line of reefs, the Fijian archipelago is dotted with reefs and extreme care is needed when making landfall. This is the case across most of the south Pacific, where the charting is notoriously inaccurate. Large areas have been poorly surveyed and never properly updated – I have heard of some atolls in French Polynesia where the charts have been four or more miles out. In Fiji, on average between two and 12 yachts are lost on reefs each year.

Modern satellite imaging and free sources such as Google Earth are fast changing this, and there are a number of smart, community-minded cruisers who have geo-referenced images far more accurately than current paper or electronic charts (we feature this next month). Nonetheless, there is no substitute for caution and age-old pilotage methods, and these are what we went to the island of Mana to demonstrate.

Neither electronic nor paper charts show any lagoon at all at Mana. But a lagoon does exist behind the coral reefs, as does a very narrow tide-swept pass through the coral reefs. To enter, you need to time the tide right and thread through to a large anchorage strewn with coral heads.

With Dan at the spreaders getting an excellent view of the pass from above and me at the bow, Em worked our way in under engine, slowly motoring ahead against a gentle ebb. Once into the entrance we were committed.

Many of the atoll passes in the Pacific are poorly marked, and the Tuamotus and the atoll of Suwarrow in the Cook Islands, for example, are completely unmarked. The pass at Mana had channel posts, but several of these had fallen down or moved from their intended positions, illustrating why conning in visually is essential.

Once inside the lagoon at Mana, we got ready to anchor. Dan attached small buoys on short lines at every 10m of chain paid out, in order to lift the cable just off the sea bed and prevent it wrapping around any unseen coral heads. While you want to avoid damaging any coral, heads rising from the bottom can be impossible to avoid if you are anchoring in a deep lagoon and hooking the chain on one can make weighing anchor again really difficult.

Castaway like Tom Hanks

After a night in Mana we left to do some more filming. In the movie Cast Away, Tom Hanks stars as a FedEx employee and postage obsessive who is involved in a plane crash over the Pacific and is washed up on a deserted island. That island is Monuriki, a small, but dramatic lump of rock in the ocean that trails a golden sand beach like the tail of a comet.

We had a brisk beat up to Monuriki under one reef, but when we got there the wind had risen sharply to 30 knots and more, and low clouds of drizzle were sweeping across at speed. Fiji is at a point in the southern Tropics that comes into contact with weather systems tracking east from Australia, yet the forecasts we received didn’t tally with reality. In any case, it was too windy to stop, and even landing briefly would have been sporting, so we turned round and enjoyed an exhilarating sail downwind to Musket Cove, slaloming between the reefs.

We all hankered after a return to Waya, a walk up the hills and the batch of special coconut lolo buns we’d ordered from a local woman in Yalobi before being hurriedly forced to do a runner in the dark, but there was no time to go back. So we set ourselves up in Musket Cove to carry out the rest of the filming and made the most those enticements that, when all the ocean sailing and navigation is done, are bait for cruisers the world over: cold beer and wi-fi.

Cruising in the Pacific

While ocean passages in the Pacific tend to be easier sailing than the Atlantic, it does have its challenges. Dan Bower of Skyelark says: “The sailing has been easier: calmer, with lighter winds and not so squally. Most of the sailing we’ve done has been with poled-out headsails.

“But the distances between ‘civilised’ ports and technical services is greater. Chandlery is hard to find and getting spares by FedEx can take weeks. It took three months for us to get generator parts. You have got to be a lot more self-sufficient and carry more spares on board.

“And the navigation is more taxing. The quality of the charts is poorer and there is a lack of

up to date pilotbooks, so finding safe anchorages and navigating among reefs, and getting into lagoons and atolls is harder.”

Our experience in having to hurry away from Waya is also typical among the south Pacific islands. Many sailors more used to conditions in the eastern Caribbean do not expect such drastic wind changes as commonly occur in this area and every year boats get into serious trouble when caught out by a sudden windshift.

You can be anchored in a sheltered spot and a 180° windshift can suddenly put the boat onto a lee shore, faced with a violent swell quickly formed by several miles of fetch across the wide lagoon. You have to be ready to leave in an instant!

Cruising in the Pacific is seasonal. The southern summer is the cyclone season, when an estimated 80 per cent of cruisers leave, either carrying on round the world or dipping down to Australia or New Zealand. Cyclone-proof harbours are scarce in the Pacific, though more are being built – there are some in Fiji, including Vuda on Viti Levu and Musket Cove. At the former, yachts are hauled out and secured in dug-out pits.

Although they may seem daunting, none of these points should deter you from setting your sights on the Pacific. I have never talked to anyone who has cruised there who wouldn’t seize the opportunity to return.

The Pacific islands are nearly all safe and friendly, there is a genuine welcome from local people almost everywhere you go, the seascape and landscape are sensational and the island cultures among the most interesting anywhere in the world. If you get the chance, go.

Dan and Em Bower

Dan and Em Bower, both in their thirties, are lifelong sailors. Six years ago they bought Skyelark of London, a Skye 51 by American designer Rob Ladd, built in Taiwan in 1986, and have been sailing and chartering her ever since, making some 12 transatlantic crossings and covering around 60,000 miles.

Before that they both worked as charter skippers and instructors, and Em has sailed in yachts as varied as a Challenge 67 to Antarctica and an Open 60 in an Atlantic storm.

When we joined them they had just left the World ARC round the world rally to continue on to Australia by themselves.

How to get the best out of eyeball navigation into a reef pass

See videos for all the parts here