Heading south to the Canary Islands signals the start of a transatlantic adventure for many European yachts. Meteorologist Chris Tibbs shares his top tips for this passage

Our focus tends to be on the crossing to the Caribbean of around 3,000 miles. If done at the right season the weather for the transatlantic stage will likely be kind and it will be tradewinds for most, if not all, of the way.

Getting south to the Canary Islands, however, can be quite a different matter. Sailing across the Bay of Biscay brings its fair share of worry. Some guides suggest getting as far west as possible before heading south, however I prefer to get to the Brest Peninsula to shorten the distance then wait for a weather window.

Getting west is good if there are going to be westerly winds all the way, but during the summer months there will often be east or north-easterly winds along the north Spanish coast, which will assist with rounding Finisterre. Last year we cruised the Biscay coast and it is a lovely area previously missed in our rush to get south – it is an option worth considering if you have plenty of time.

The best time to cross Biscay is July and August when the Azores High has moved north and in south Biscay the winds are often north-easterly. When this is the case the main concern is an acceleration zone on the north-west corner of Spain. With an easterly or north-easterly wind direction there is a significant increase in the wind speed; I would add an extra 10 knots or so to the forecast to take account of this acceleration, which will also create a short, steep sea.

Article continues below…

Tradewinds explained: Everything you need to know before sailing across the Atlantic

A transatlantic tradewind crossing from the Canary Islands to the Caribbean is on many a sailor’s bucket list. Endless sunny…

Sailing Biscay: Top tips for a safe and smooth crossing of the notorious bay

Biscay has a fearsome reputation and for many sailors, it is their first taste of bluewater sailing. Distances may not…

In these conditions I prefer a passage close to Finisterre to minimise the time spent in the acceleration zone and also to get some shelter from the waves. With a well-established Azores High and the ‘normal’ heat low over Spain the Portuguese trades will set in. Driven by the pressure gradient between high and low pressure these will be strongest during the afternoons then easing near the coast at night.

Offshore they will tend to stay strong from a north to north-westerly direction and 30 knots is not unusual; it is a good way of testing your downwind sails for the transatlantic! As we get later in the season, from early September onwards, depressions in the Atlantic will track further south giving strong south-westerly winds in Biscay and pushing the band of Portuguese tradewinds south, often south of Lisbon.

This makes a Biscay crossing difficult; it is still possible but we’re likely to have to wait some time for a weather window and once we have one it’s a hard push to cover the miles. Departing from southern Portugal or from the Mediterranean, statistics suggest we should have north to north-easterly winds for the majority of the passage.

When leaving from the Med it’s important to get through the Strait of Gibraltar with an easterly wind – the Levante. The geography of the area funnels the wind strongly between the mountains of Spain and those of North Africa, making the straits difficult in a westerly. Once out of the Med the route joins with that of boats from further north.

It is usual to have to get some westing before heading south to avoid an area of calms often found along the Moroccan coast, near Casablanca, which is caused by low pressure over North Africa. With northerly winds in place there will be an acceleration zone west of the Atlas Mountains. The mountains funnel the air along their western side and a band of strong wind can be found up to 100 miles offshore.

This will be forecast to some extent if using GRIB files, although I think it is often underestimated in the forecasts. It is more of an issue if heading for Lanzarote from Gibraltar as our route is generally closer to the coast than if arriving from Portugal.

Cut off low

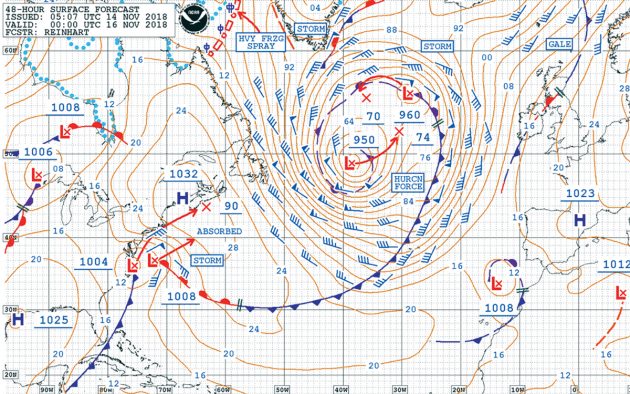

The feature of more concern is a ‘cut off’ low. These are small lows that form on the southern part of a loop in the jet stream. They form, then the loop tends to collapse and the jet stream moves north.

This leaves a small low without the driving force of the jet stream to steer it. The low will then drift around, sometimes towards the north-east, but just as likely drift west before slowly dissipating.

These lows will often have strong winds in them; being so far south just a small pressure gradient will give strong to gale force winds and it’s not unusual to have an exciting passage heading south if encountering a cut-off low.

The passage to the Canary Islands can be a lovely sail and a preview to tradewind sailing – but you do need to watch the weather.

Top tips for sailing to the Canary Islands

- Leave early in the season – from September the weather can quickly deteriorate.

- Shorten the distance, particularly in unsettled weather.

- If the wind is easterly or north-easterly in southern Biscay expect a significant acceleration zone around Finisterre.

- The Portuguese tradewinds can be strong.

- Watch for cut off lows forming.

- Moderate easterly winds in the Med will give gales in the Gibraltar Strait.

- Watch for an acceleration zone close west of the Atlas Mountains (near the latitude of Marrakesh).

About the author

About the author

Chris Tibbs is a meteorologist and weather router, as well as a professional sailor and navigator with more than 250,000 sailing miles behind him. He forecasts for Olympic sailing teams and the ARC rallies, among others.

First published in the September 2019 edition of Yachting World.