It looks futuristic. It has no cockpit nor aft deck. Are we ready for a radical 56ft catamaran with a potential average speed of 15 knots? Toby Hodges finds out

Broadblue Rapier 550 boat test – Are you ready for a 54ft catamaran that steers like a car?

Marty McFly, Michael J Fox’s lead character in the 1980s film Back to the Future, breaks into a wild electric guitar solo while playing a Chuck Berry number during a 1955 high school dance. The audience is stunned into silence. “I guess you guys aren’t ready for that yet,” he declares, embarrassed.

That scene came to mind as I approached the Broadblue Rapier 550. I wondered if we were ready for such a radical-looking British boat. Sailors may be forward in embracing new technology, but we remain sceptical about change to our boats. We want to know something works before setting out to sea.

So a contemporary design like this, brimming with new ideas about how to sail offshore quickly yet easily, is one most will view with scepticism. And that’s before they wonder where the cockpit or aft deck is – or the winches for that matter.

The answer is inside. Step aboard the Rapier 550 and your jaw drops. This is an entirely new breed of boat, one that could appeal to monohull, multihull and motor boat cruisers. She is designed for fast ocean cruising and potentially she can reel off 350-mile days at an average of 15 knots.

An inside job

The real eye-opener is that she can be controlled by one person from an internal cockpit. We are used to unusual cockpit layouts on multihulls, but the only other yacht I know to have tried an internal version is the 59ft catamaran Impossible Dream, designed by Nic Bailey for wheelchair use.

And it was Bailey who again teamed up with Darren Newton and his Multimarine yard to create this more refined and rather futuristic production boat. But does it work and is it safe? And more pertinently, are we ready for it?

I was debating these questions as I boarded the Rapier at Gunwharf Quays in Portsmouth. Within all that glass, I found a vast open-plan area: a saloon and galley with abundant space and light, plus a cockpit and bridge area forward. This ‘cockpit’ is the centrepiece of the boat.

Broadblue wanted to produce a boat that could be sailed single-handed without compromise on performance. MD Mark Jarvis explains: “This means one person can sail it from anywhere on the boat.” To achieve this an ingenious winch station was designed around the mast compression post. All sheets and running rigging can be worked via three electric winches. Two of these are reversible, which, together with a digital switching system, means sheets can be trimmed or eased remotely, as can the traveller – more on that later.

Broadblue says this all-encompassing superstructure means there’s no need to go out into an exposed cockpit and lets the builders dispense with an extra bimini or furniture to create a simpler, lighter yacht.

Remote-controlled

I remained sceptical as to how practical the theory would prove at sea. Indeed, during our trials the word ‘foreign’ soon filled my notebook. To sit at the bridge feels odd enough; I was uncomfortable at not being able to see the mast from the helm. But when you sail her the Rapier seems truly alien. With her car’s steering wheel and seat for helming, her remote manoeuvring and operation, she will feel more familiar to motor boaters than yachtsmen.

Just leaving the dock puts you into unfamiliar territory. It can be done from the two leather Recaro racing seats while watching aerial footage from a mast-mounted camera. Or there’s the option to use a remote control for the twin throttles from the side deck – a more practical option on a boat of 26ft (8m) beam.

Remote control functionality is at the heart of the Rapier. Her two reversible winches and traveller can be operated from four positions: there are dedicated buttons by the winches and the interior and exterior helms, plus a handheld remote which works anywhere on board. I was in the pilot seat as the whirr of a winch behind me informed me we were hoisting sail – Jarvis, remote control in hand, was monitoring the hoist through an aft hatch.

To hand-steer the Rapier using the wheel feels strange because there is no feedback. You have to wait for the lag in the hydraulic linkage after turning the Italian racing wheel slightly. Monitoring the rudder offset gauge on the autopilot display also helps.

But the unimpeded view forward from the bridge is extraordinary. The full jib can be seen, but try to monitor the telltales and you’ll get neck ache (trust me on this). So I steered by numbers – and finally I began to appreciate this boat. Quite simply, she is the easiest and most comfortable yacht to sail at double-figure speeds.

We sailed upwind, matching the true wind speed at 40° to the apparent breeze, with no noise, no heel and no wake. I felt as though I was in a simulator; as if I was watching the Solent slip by on a screen such was the utter comfort and ease.

No wet weather kit needed here.

The instruments are the only indicators of the conditions. Speed is gauged only by a sudden deceleration during a painfully slow tack – it feels something like falling off the plane on a powerboat.

The inner sailor in me was itching to get out – I wanted to feel the boat. Thankfully, the Rapier allows carbon tillers to be mounted directly over the stocks on each quarter for a wind-in-the-hair experience.

A button push to exchange helms and I was tiller-steering this 55ft spaceship.

Wind-in-the-hair sailing

This was more like it! The feedback is direct, even if currently a little stiff. Remote switches located on coamings beside the tillers also provide the ability to trim the sails, combining with tillers to give sailors everything they may be missing. As such, she is incredibly rewarding for a large multihull. At 11 knots close-reaching, the Eastern Solent flashed by in minutes.

Off Gurnard we set the asymmetric and ran some deep angles to get back east past Cowes. The 550 exceeded the single-figure apparent wind speeds, averaging over eight knots, despite running as deep as possible (140-160° true). Heat her up a bit and the Rapier’s acceleration is instant, a testament to her lightweight build.

I did get used to steering from the wheel inside, but I never reconciled myself to being unable to see the mainsail. I was reportedly at the tiller and wheel for longer than anyone had been to date, but Jarvis told me the sailing we did was unusual for her design: “She is designed for long-distance bluewater sailing, so lots of autopilot use, chewing off miles with everyone in comfort.”

Her designer, Darren Newton, put it more bluntly: “We’re all liars. We all believe we are Volvo skippers, wanting to be outside with spray in our faces. It’s not about doing 20 knots plus. It’s about doing 15 knots and averaging a safe, good pace with the family.”

The Rapier certainly offers comfort on passage. Whether on or off watch, the space and light below is astonishing and the Rapier’s forwards focus helps connect crew to their surroundings. The views forward are more like those offered by a motor cruiser.

The catamaran Impossible Dream, developed 12 years ago, has 48 hydraulic operations to facilitate her internal helm station. For the Rapier, the same designers have managed to use just three winches to provide the same functionality thanks to modern reversible technology.

This internal cockpit has been designed beautifully. The whole area around the carbon compression post is more like a work of art than a winch-pit. The clutches and winches have been sited so that there is always a winch free when needed. Large, stiff canvas buckets keep all tail ends tidy, and drainage has been well considered.

The issue I had with this ‘sail station’, however, concerned the safety of mounting such powerful winches in the living area. Four different switches can operate the two reversible winches from a variety of positions, so it only needs a hand to be in the wrong place for a potentially very nasty accident to occur.

Safety measures

We have recommended to Broadblue that an emergency stop button be fitted and a winch guard be designed. Jarvis says they intend to create covers that can be fitted while sailing – a practical solution as once sails are set the sheets/halyards rarely need to be swapped on a winch other than for a sail change. If power is lost, winches can be manually operated, including the traveller.

The Rapier has a French safety system called UpSideUp that alerts owners to changing conditions and can be used to depower the boat automatically if no action is taken once set parameters are exceeded. It is a prudent system to have for a powerful, fast boat designed for short-handed sailing.

Another factor to the Rapier’s operation is the EmpirBus NXT, a node-based digital switching system used for all push-button electrics. A control panel in the middle of the dashboard gives diagnostics on electrical systems, pumps and liquids, lights, alarms, autopilot and fuses.

Siting the bridge and internal cockpit forward leaves a one-level living area of a size unrivalled by any boat of this length. It’s like being in a floating conservatory of tempered, tinted glass. Doors, aft windows and a skylight that all slide open prevents the Rapier from feeling stuffy, however.

The abundant views and light on offer proved exceptional at sea, but at night it is hard not to feel like a goldfish in the proverbial bowl. Blinds would come very near the top of my options list.

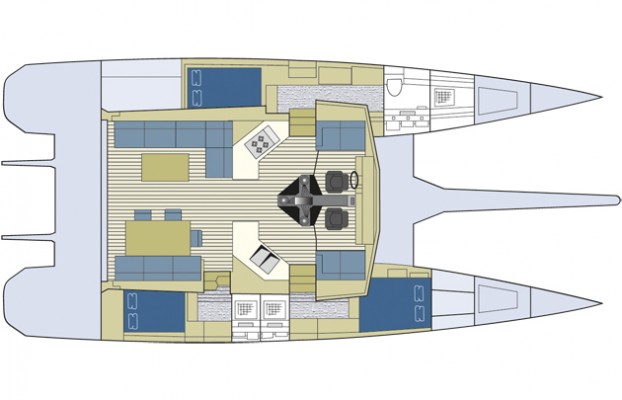

The layout of the main living area can be customised. For the first Rapier we sailed, Nic Bailey designed a split galley and saloon for an open-plan yet cohesive feel. Darren Newton wanted the mast base aft to allow for large foresails, so the bridge is on a raised section forward of the compression post.

This is the only area on the boat where headroom is constricted, but a hatch allows the helmsman to communicate with crew on the foredeck. A sofa each side of the helm encourages fellow crew to sit alongside the helmsman in comfort (and facing forward). This helps them to engage with the sailing rather than head for shelter and leave the helmsman alone on deck.

The saloon and galley can be custom-designed. The test boat had a carbon coffee table to port which adjoins to the sofa to become a daybed

Wow factor below

Part of the port hull is given over to an owner’s suite. By positioning this fairly far forward, the berth has maximum beam and there’s room for a dedicated technical area aft. This houses the machinery and electronics, plus a workbench. A problem with this is that the genset is mounted directly abaft the owner’s headboard – the last place noise or vibration is wanted.

Owner’s cabin: this area has a technical area aft, which offers good access to all the Rapier’s machinery

My main gripe, however, concerned the finish, especially considering the quality of the Rapier’s build. A French firm was contracted to do the Alpi woodwork, much of which, including the locker doors and grain, didn’t line up neatly. Elsewhere, the Rapier seemed as though she had been finished hurriedly. She still has plenty of wow-factor, especially lit up at night, but potential owners will be expecting a more polished interior finish.

Two bright, spacious double en-suite guest cabins are located in the starboard hull. These are stylish and roomy, but again I thought they lacked finishing touches and locker space in the heads.

Specifications

LOA 16.76m/54ft 11in

Beam (max) 8.00m/26ft 4in

Draught 1.30m/4ft 3in

Disp (lightship) 9,800kg/21,605lb

Berths 6-8

Engine 2 x 40hp on shafts diesel. Electric hybrid option is available

Water 550lt/120gal

Fuel 300lt/66gal

Mainsail 110m2/1,184ft2

Jib 50m2/538ft2

Gennaker 120m2/1,292ft2

Spinnaker 200m2/2,153ft2

Designed by Broadblue Catamarans

www.broadblue.com

Conclusion

This boat is well very designed and built, and her designers deserve credit for lateral thinking. The interior volume, forward-looking bridge, option for tiller-steering and lightweight build combine to make this the most complete fusion of motor boat, performance yacht and liveaboard I have seen. She is a comfy, mile-munching machine suitable for short-handed sailing.

The obvious appeal is to motor boaters. They are more likely to put their faith in her systems and appreciate the driving position. I was sceptical about whether the outside-in approach would work at sea, but I have to admit I came to appreciate the idea. It’s about accepting a very different concept; as designer Darren Newton says, “it’s about being honest about how we sail offshore today”. It was certainly the most comfortable tour of the Solent I have ever done.

The hard work has been done, all the finite tooling created to build a solid yet light boat, but she lacks some of the fine polishing I’d expect for her £1.5m price. And I have reservations about the safety of the remotely controlled winches in the internal cockpit. All these things can be corrected, however.

The base price of the Rapier is similar to that of the Jeanneau 64 we tested last month. Their volumes and living areas are comparable. The Rapier’s speed will allow you more time at anchor and she won’t need a crew. She is also customisable, but will cost a third more over her base price to hit the test boat’s spec.

So the question is whether the Rapier is ahead of her time, like Marty McFly’s guitar solo in Back to the Future. Are we ready for this futuristic cat? I think so and believe her innovation should be encouraged. Given a few improvements, she will appeal to an increasing crossbred market sector – one that is honest about the cruising they want to do.