Heaving to is an ideal technique for riding out a storm, but there’s an art to it in heavy seas. Skip Novak explains how to go about it

Heaving to in light to moderate wind is easily achieved by gybing or tacking and leaving the headsail aback. A lashed helm and maybe an adjustment on the mainsheet puts on the brakes and the boat lies off the wind, virtually dead in the water. Whether to take a break to make repairs and cook a meal or to wait for a rendezvous, perhaps, this is an easy way to stabilise the boat, so that you can do whatever you need to in comfort.

Doing it when storm sailing is another story, however. You will be under reduced sail to begin with, and more options of trim come into play.

There comes a time when thrashing to windward in high winds and big seas while going nowhere becomes a useless exercise, not to mention a potentially dramatic experience. Not only is crashing off waves bad for the boat, sails and gear, it is also tiring for the crew – full attention is required even if you are on autopilot. So, it might be prudent just to stop the boat until the weather passes, even if you are only reaching or sailing downwind. Approaching a lee shore is a good example.

Out of control

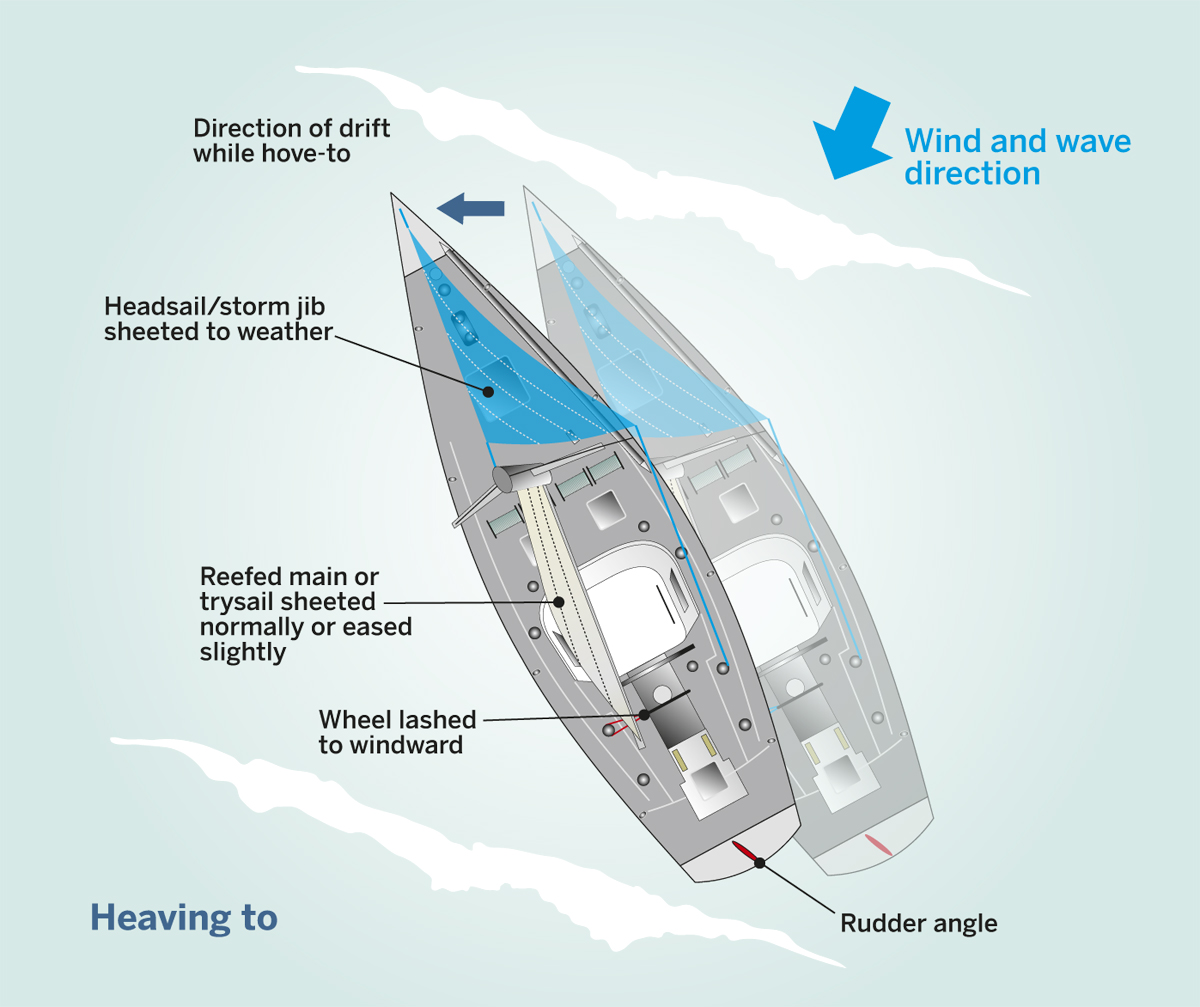

The art of heaving to in heavy weather is complicated by the sea condition. Get it wrong and the boat can go wildly out of control for a time. The trick is to stop the boat’s forward progress, balance a very reduced sailplan with the angle of the rudder to windward and attempt to lie around 45˚ into the wind and sea.

When you achieve the correct balance, the boat is alternatively scalloping into the wind and paying off to leeward. When we say ‘rudder to windward’ that means a tiller would be pushed to leeward and a wheel would be pulled to windward, in effect trying to steer the boat into the wind.

The only downside of this technique is that the boat, depending on how well it heaves to, will make leeway downwind, which can be several knots. Therefore, if inshore, utmost caution must be used and you must not let your guard down while on a lee shore. If there is a threat, it might be better to soldier on for a time until you have ample sea room, taking into account the weather forecast and prevailing current.

If heaving to is executed correctly, though, the crew can go below, cook a meal in relative comfort and stand a watch from the pilothouse (if you are lucky enough to have one).

The reality is that if you are not making any substantial VMG in the direction of the wind in fresh to gale conditions, it is best to heave to, take the loss in leeway on the nose and wait for the weather to change. Odds on you will be a winner.

The dilemma is that every boat heaves to in different ways and some designs don’t heave to at all. Older, traditional designs with a bigger keel surface are generally more responsive, whereas more modern designs struggle to get any bite into the wind and tend to lay off, making an unacceptable amount of leeway. There is also a risk of damaging a high-aspect spade rudder when ‘back pedalling’ with a big wave, so beware all of you with performance cruisers.

So, the message is to get out there and practise. Heave to in increasing winds and sea states to see which system and configuration works for you. Below is how I do it on Pelagic, assuming by this stage we are down to a third or fourth reef and storm jib on the staysail stay (see Part 3 of this series).

How Skip heaves to

1 Back the staysail to windward by trimming the windward sheet. Don’t gybe because the boat might fly down a wave and tacking might be impossible. Beware of chafe issues on the windward rigging. Long shroud rollers come in handy on the lower shrouds. If you have a big staysail, it’s best to roll it up to handkerchief size.

2 Ease the reduced mainsail until the boat stops all forward motion.

3 Put your rudder over hard to windward (ie with the wheel lashed to windward or the tiller lashed to leeward), taking care that the boat does not go head to wind. Lash the helm well, so it can’t ‘work’.

4 Play with the mainsail trim until a balance is struck at a good angle to wind and waves. The ride should be comfortable.

5 If there is still too much tendency to climb to windward, drop the mainsail. This would probably be the case if you had a third reef, which would be too much sail. A fourth reef (storm trysail size) might work.

6 Keep a close eye on the boat for some time to make sure it stays in balance during various cycles of wave and swell patterns.

7 Crew can go below. One watchkeeper is sufficient, booted and suited to go on deck to make any changes.

Of course, this is only the configuration on Pelagic – you need to get a feel for what is possible on your boat. It’s all about a balance between what is below the waterline (keel and rudder) and windage above (sails and rig). Even with the main down, a simple manoeuvre like easing the boom against a solid boom vang can change the tendency to climb into the wind. Ketch and modern schooner rigs have more possibilities still.

Other tips

- Always check your sea room and probable drift rate in view of the weather forecast.

- Heave to earlier rather than later – it is much easier to set up in a controlled situation. If the wind is rising, there is no point waiting– not much distance will be lost.

- Prepare the interior well because big rolls are inevitable.

- Make sure that all furling sails cannot unfurl by themselves.

- Make sure all running rigging is well stowed – a line overboard when heaving to invariably finds its way around the propeller.

- When the wind drops or shifts with a front, beware! Start out softly. Sea conditions will remain on the up for a time and are likely to be confused. So, don’t let down your guard and remain harnessed on when making sail.

Part 5 reefing

Putting in a reef in heavy weather needs to be done in good time and requires careful planning. In the next episode of this year-long series, Skip Novak takes us through the process step by step