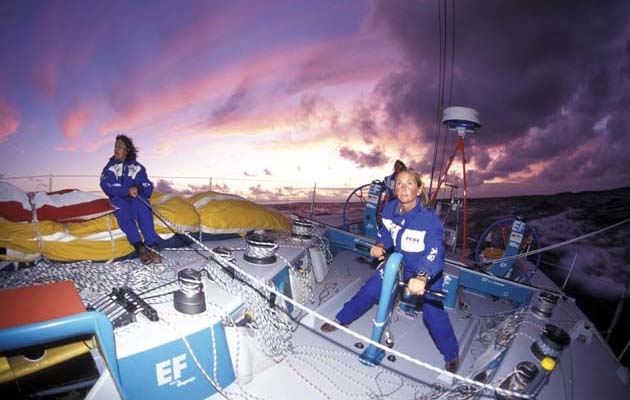

Tom Cunliffe introduces an extract from Mark Chisnell's book, Risk to Gain with vibrant, classic imagery by Rick Tomlinson.

It’s hard to believe that almost 20 years have elapsed since the Swedish EF team of two boats took on the Whitbread Round the World Race in 1997-98, writes Tom Cunliffe. In at the birth of the Code 0 sail, EF Language proved the eventual winner. EF Education’s all-women crew completed the course in fine style and were not disgraced in the placings.

Looking back on these epic contests we are fortunate to have Risk to Gain, a large-format book from Mark Chisnell with images by Rick Tomlinson. As a photographic record, the book would take some beating. Much of the text, skilfully compiled by Chisnell, comes from the words of Magnus Olsson on Language and Anna Drougge, sailmaker on Education.

This extract is Anna Drougge’s fascinating insight into the details of a dawn watch in the tropics where almost nothing of note happens as the Whitbread 60 creams along in state. We can almost feel we’re there . . .

Risk to Gain: an extract

“The hand on my shoulder was light. I turned quickly and looked up, eyes open, but unseeing. ‘Ten minutes,’ said the voice. I stared at the underside of the deck above me until the world came into focus. A trickle of condensation rolled off a screwhead and slid down the hull until it disappeared. The silk sheet was twisted around me, damp with sweat.

I rolled clear of it and slid off the bunk.

The boat’s motion was easy, the sea flat. I fumbled in my bag for the still-damp shorts and T-shirt. Leah, who came on watch with me, was just stirring from the other top windward bunk. Dressed, I found a water bottle and filled it, before climbing up through the hatch and peering into the soft light of dawn. I flipped my sunglasses off my forehead and into place – it was bright enough to need them. And it was still blisteringly hot, which was no surprise when you consider that the water temperature had only just dropped below 30°C.

Katie glanced across at me from the leeward trimming position and mumbled: ‘Hello.’ She didn’t have sunglasses on and I could see her eyes were bloodshot, tired from the night watch, from the strain of peering at the sail in the dark, trying to pick up the shape and movement of the telltales with the torch.

I struggled out of the hatch, moved down to leeward and stuck my full water bottle in the forward tail bag. ‘Anybody seen the sunblock?’ I asked of no one in particular, and no one replied. I checked the two leeward bags: ropes, a soggy power bar wrapper, two empty water bottles and a torch that didn’t work, but no sunblock.

I moved up to windward and checked in both those bags, and there was nothing there either.

Life on board in the Tropics, as crew work in T shirts and shorts, taking their turn on the helm.

Spinnakers and sunblock

‘Anybody seen the sunblock?’ I said again, a little more insistently, moving aft as I checked around the faces.

Melissa glanced away from the mainsail leech telltale. ‘We haven’t touched it.’

I stuck my head into the bag on the leeward side of the mainsheet grinder.

‘It’s been dark,’ said someone, with more than a trace of sarcasm. But I didn’t care, I’d found it. I held the bottle up triumphantly to the group and pulled a face. They all smiled. I moved up to the windward side and sat on the sail stack while I smothered myself. I checked my watch: just before 0600. I slid forward again.

‘So what’s happening, Katie?’

She looked back at me, turning from the headsail. ‘The wind eased back a little about three hours ago, and moved right a touch, so we went with this.’ I glanced up at the A3.

Katie was still talking. ‘We set up for a spinnaker, in case the wind kept going. But it’s been pretty stable ever since, just rolling us up the track, nice and easy.’

I nodded and cast my eye critically over the huge sail. The so-called Monstas, Code 0s or Whompers had caused a lot of fuss early on. Team EF had been the first to develop the sail, and the crew on Language had used them to impressive effect on the first leg. The other skippers had stirred up trouble in Cape Town, but the race officials had confirmed that they were legal, and the rest of the fleet had been playing catch-up in sail development ever since.

The controversy centred on the fact that, although the sail measured in as a spinnaker, it could be used at wind angles that were normally the territory of headsails. Because spinnakers could be raised to the masthead, rather than just the hounds, the A3 had an enormous amount of extra sail area compared with a conventional headsail, and in light to moderate breezes that translated directly into speed.

Another sail change: Whitbread 97/98 Team EF Education

‘I was thinking maybe I should ease the guy a touch,’ said Katie.

‘I was wondering about that too.’ I scrambled aft to where the leeward after-guy was made up on the runner winch drum. The A3 was hoisted on the masthead spinnaker halyard and fastened to the downhaul at the bow. It was furled when we set it and dropped it, because the sail was impossible to hoist loose.

Once it was up, we controlled the sail by using the leeward spinnaker sheet run onto the primary winch drum, as well as the leeward after-guy. The turning blocks for both sheets were on the gunwale, but the after-guy lead was much further forward and allowed us to put tension almost directly down the leech. The spinnaker sheet tensioned the foot. By juggling these two sheets, you could get the sail shape you wanted.

‘You happy?’ said Katie as I sat back beside her, adjustment complete.

‘Definitely,’ I replied. She handed me the sheet and I slid into her place by the winch. Katie was gone in a moment. I glanced aft: Melissa now had the wheel; she would go down at 0800, along with Bridget and Keryn. Leah sat with Melissa on the high side, getting a feel for the conditions in the same way that I had with Katie.

I popped in some chewing gum and eased the sheet a fraction, Keryn cracked the mainsheet off behind me. The A3 is so big that the mainsail has to be trimmed around it – if we eased the leech of the A3 then we had to ease the mainsail leech to maintain the parallel slot. The wind speed jumped up to 13 knots, the wind angle steady around 110°. The first morning watch change was complete.

‘Whoa, dolphins!’ shouted Leah a couple of minutes later. I turned round to see her bounding towards the companionway. I knew where she was going – Leah was responsible for all the video and still photography shot on board. We had seen an extraordinary amount of wildlife, but no matter what amazing creatures we saw, Leah could never resist the chance for some dolphin photos!

Whitbread 97/98: EF Education on leg 1.

It was 0730 when Bridget slid past me to get breakfast started and 15 minutes later nothing else had changed.

I hadn’t touched the sheet or guy. In those circumstances we can afford a couple of people below, and I slid down for a breakfast of cereal with some freeze-dried fruit. There was no coffee. With only two days to turn the boat around in São Sebastião, somehow the coffee had got left behind. Maybe that wasn’t such a bad thing, we saved a lot of gas by not having hot drinks.

But it wasn’t the only thing we were missing. The minimal rest had left everybody jaded. It hadn’t been a problem until we had hit the demanding conditions of the Doldrums. Perhaps our concentration wasn’t there, or maybe we had just been unlucky. Either way, we got nailed by more bad clouds than anyone else. We had fallen off the back of the fleet and had been reaching ever since, with little opportunity to catch up, and none to overtake. Sometimes sailing could be a brutal sport.

When I had finished breakfast I swapped with Leah at the wheel and she ate with the three coming up. I watched Bridget, Keryn and Melissa go below with more than a little envy. Still, I was steering now, which made a change from staring at the headsail. When Leah returned she took over the trimming, Marleen was on the mainsheet, Lisa grinding for her and Joan sat on the gunwale, near me.

‘Puff coming,’ she would warn occasionally and we would bear away just a fraction. The big sail loaded up frighteningly quickly. She had been staring at the horizon silently for a while, when she asked: ‘What day is it?’

‘Huh?’ I glanced at her.

‘What day is it?’

I looked back at the boat speed read-out: I hadn’t lost anything through that glance away. ‘I’ve no idea,’ I said finally. ‘Maybe Tuesday or Wednesday, why?’

‘No reason. I just wondered. Have you got any gum?’

I fumbled in my pockets and handed her a piece. Then she lapsed into silence again, until Lisa tapped her on the shoulder to swap onto the mainsheet grinder. Not that there was a lot of grinding, the wind was relentlessly steady. The boat was beautifully balanced, fully powered up, water tanks full, sails stacked, the sea flat and a cloudless sky. It was perfect sailing weather.

Fuelling up down below: Whitbread 97/98 EF Education.

‘You know,’ said Lisa, now sitting beside me, ‘I think the wind might be getting up a little. I was thinking I might set the sheets up for the reacher. In case we have to change.’

I looked at her doubtfully. ‘I haven’t really noticed it myself, she still feels pretty comfortable to me.’

‘Yeah, but just in case.’

‘OK.’ It was, after all, something to do.

Lisa peeled off the rail and moved forward. The job didn’t take her long. But an hour later the wind, if anything, was easing a little and moving aft, to the right.

‘I think it would be spinnaker next,’ I said to Leah.

She looked back at me, then at the instruments, then back to Lisa on the handles. ‘You want to set it up?’

Lisa nodded and Joan dropped off the rail to take her place. Inevitably, ten minutes later the wind had gone back to where it was before. I swapped with Leah and went back to the headsail trim.

I glanced at my watch. Two hours to go before we were relieved. I turned back to the others. ‘Shouldn’t there have been a sched about now?’

Education was one of two identical boats in the 1997-98 Whitbread Race. EF Language won the event.

Beautiful day

Leah was at the wheel, and didn’t take her eyes off the headsail as she replied: ‘Probably.’ She hesitated; I watched her gaze shift to the instruments on the mast, and then back to the headsail again. ‘Do you really want to know?’

I looked back at the telltales myself. The windward bottom ribbon was lifting slightly, so I wound the sheet on a touch and it came back into line. I heard the mainsheet grind round the drum behind me in sympathy. The boat speed flickered up a tenth of a knot. Finally I looked back at Leah and sighed. ‘Probably not,’ I said.

The last hour crawled by. It was Katie appearing out of the hatch that told me the watch was finally done. She stepped onto the deck and stretched. She peered slowly around the horizon, before alighting on the Code O. ‘Same sail,’ she said, more statement than question.

‘Uhuh,’ I replied.

She peered up at the trim, then rested her gaze on the instrument dials. ‘Same course.’ Another statement.

‘That too,’ I answered.

‘And certainly no new boats to see. What about the wind?’

‘It went up a bit, went down a bit, pretty much the same.’

There was a silence, while she once more scanned the horizon, all blue sparkling ocean and puffy white clouds. ‘Beautiful day though.’

I looked up and smiled at her. ‘Just another day at the office.’

Risk to Gain by Mark Chisnell and Rick Tomlinson is published by Max Strom 1998. ISBN 978-9175 882260. Available second-hand from online stores