From start to finish, sailing the Atlantic from Senegal to Guyana with a crew of marine scientists and environmentalists was an extraordinary experience. By Emily Caruso.

A very wise man once told me that there are two kinds of sailors: those who have been aground; and those who lie.

One day in December last year anyone on the banks of the Essequibo River in Guyana would have beheld a most unlikely sight. Surrounded by the vibrant green flora of the Amazon rainforest, the former Global Challenge yacht Sea Dragon was gently listing to starboard as she sat haplessly on a sandbar just a few miles from the destination port of Bartica.

The 72ft yacht was quite a spectacle and, with an all-female crew of expedition scientists and sailors, it was no surprise to find that our unscheduled stop generated much interest from passing fishermen and ferry boats.

A plague of insects rained down

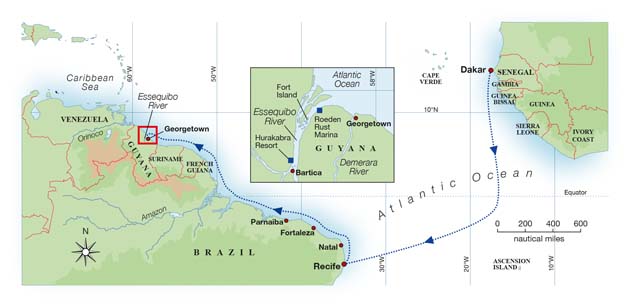

The journey that brought us to this sand shoal began, for me, in late October when I joined the yacht as first mate in Senegal, West Africa. After preparing Sea Dragon in the vivid orange city of Dakar where, on land, the heat was punishingly hot and the pollution overwhelming, we headed across the Atlantic to Recife in Brazil, before crossing the mouth of the Amazon on our way to Guyana. Our remit involved collecting water samples for the study of microplastics and toxins within the lesser-explored sections of our oceans.

The crew was made up of 14 women, including scientists and artists from the UK, US, Canada, Norway and Italy, together with three professional crew (skipper Imogen Nash, myself as first mate and second mate Holly Vint). Within the crew there was a wide variety of sailing experience – some had sailed offshore, while others had never set foot on a yacht before.

Sea Dragon is a former BT Challenge round the world racing yacht that has been refitted for use conducting ocean research.

The drama began almost immediately after our departure from Dakar as we headed south towards our first planned destination of Ascension Island. Just 60 miles from the Senegalese coast I was woken by a most unusual noise. It was the distinct and deafening high-pitched whistle of crickets, but it appeared to be coming from on deck. As I hurried into the saloon and glanced up at the deck hatches, the mosquito nets were teeming with large black insects scuttling across each other trying to find a way into the boat.

The decks were littered with the creatures as the on-watch crew looked on with disbelief. We didn’t know whether to be alarmed or amused at first, but bemusement soon gave way to a sense of growing urgency as the infestation progressed around the boat. Literally thousands and thousands of them began to bury themselves into the sails, the rigging, the blocks, the dinghy, the halyards, the spinnaker poles, everywhere.

The insects soon began to appear below decks too and a whistling sound emanated from inside the hull. They would appear from behind the navstation electronics and the possibility of damage became increasingly evident.

We began the clean-up operation using the Aquavac and a high-pressure deck hose, with the crew working tirelessly and methodically from bow to stern. As the day gave way to night the cabin lighting attracted more and more into the living quarters, the galley and the bunks. One by one our unwanted visitors were evicted – the last surrendering a full two weeks after they first joined us.

Perfect tradewind conditions off the coast of Brazil.

Transatlantic trawls

Sea Dragon motor sailed through the light and fickle winds of the Tropics before the Intertropical Convergence Zone brought us some welcome breeze, albeit in the unpredictable squalls of the Doldrums. We were sailing the vast expanse of the ocean known as the Pelagic Zone, which is known as the ocean equivalent of the desert, with little presence of sea life other than the microscopic examples we recovered in our samples every day and the odd sea bird or flying fish.

We marked the crossing of the Equator with a ceremony in which the crew wore sarongs and gold body tattoos, until the south-easterly Trades eventually presented themselves, allowing us to maintain a steady sailplan. As we had envisaged, the course had us hard on the wind and the planned stop at Ascension became untenable. So instead we bore away, eased the sails and set Sea Dragon on a direct course for Recife, Brazil.

Each day was spent gathering scientific data through water sampling and by trawling the surface water using a bespoke device called a Manta Trawl. We would trim the boat to maintain a steady speed of two knots through the water and rig a line through a block at the end of our spinnaker pole set to windward, on which the trawl would be rigged at surface level.

The specially designed trawl device is towed from the spinnaker pole for 30 minutes each day at exactly 2 knots.

At the aft end of the trawl a removable ‘cod end’ was affixed, comprising a fine net in which we were able to gather our samples for study under the onboard microscope. Our sailplan changed just once a day to drop the staysail, engage the engine and deploy the trawl. Each trawl lasted for half an hour, before its contents were sorted and analysed under microscope in the saloon.

Amid an abundance of plankton, the evidence of small particles of plastic was unambiguous, despite the fact that the nearest land was often thousands of miles from our position. I found that every time a plastic bottle floated past, my stomach sank a little lower.

Arrival in Recife, with its developed skyline and electric blue water, was in stark contrast to the deprivation we saw in Senegal. The stopover enabled us to complete some urgent maintenance tasks, and it was also time for a crew change, after which we began the second leg of our expedition, sailing north along the east coast of Brazil, for our second Equatorial crossing of the trip.

This time the Trades allowed us to reach with a prevented main and poled-out yankee giving us good speeds throughout. Enviable conditions culminated in a steady 15 knots of apparent wind on the beam, under a display of remarkable meteors one night. We maintained a course 200 miles from the coast, which put us in international waters and outside the economic exclusion zone to prevent any ownership issues in relation to the data we were collecting.

Aground in Guyana

The night before we began our epic journey up the Essequibo River in Guyana we held station 20 miles offshore, surrounded by fishing boats, to await daylight, as advised in the pilot guide. High water the next day gave us safe passage across the shallows as our pilotage began, but there were some tense moments as the sounder recorded as little as 0.6m beneath us – an early indication that the charted depths in both paper and electronic were to be treated with great caution.

We anchored overnight at Roeden Rust, which provided us with firm holding and a pleasant overnight in water the colour of chocolate. The following morning we set off at low water to maximise the flood tide for our next leg to the Hurakabra Resort near to Bartica. As we made our way upriver the banks drew closer and at times we were just 30m or 40m from the bordering rainforest.

We passed the colonial fortifications on Fort Island, once the capital of Guyana, and colourful wooden houses would periodically be seen on the riverside and children ran down to the water’s edge to wave to us excitedly as we passed. We gently touched the bottom a couple of times and altered course accordingly as we felt our way through, ever aware of the 4m draught of the keel below us.

We began to study the ripples on the surface of the water and slowly edged our way further along, the clock constantly ticking as the flood tide carried us on our course. The chart was telling us where the sand banks had been in 1927, but even with the use of some recent GPS waypoints, we were effectively navigating blind as the riverbed is always changing.

If our RIB engine had been working at this point we could have sounded ahead, but despite the assistance of an engineer in Recife it was not reliable. Besides, the current was too strong to use a lead line.

Brute force and persuasion in our attempts to free Sea Dragon from the river bed.

With just two miles to reach our final destination and painfully close to the top of the tide, I felt the hull lunge to a halt beneath us. Despite a swift response on the throttle it became apparent that Sea Dragon wasn’t going to move on under engine alone. We were just a boatlength and a half from a 10m deep hole in the riverbed, which was soul-destroying so near the finale of an expedition which had carried us over 4,500 miles.

The following hour was extremely tense as we tried every trick in the book, utilising the boom, halyards, anchors, crew weight and engine to try to move Sea Dragon off the riverbed, but as the current rapidly began to ebb, we prepared to overnight aground.

A local man dived beneath the hull to ensure there were no underlying hazards other than that of the shoal itself. We secured all seacocks and hatches and arranged for the crew to pack a few essential items ready to spend the night at the nearby Hurakabra Resort.

With the help of the locals we evacuated the crew safely ashore and skipper Imogen, Holly and myself remained on board to monitor the angle of list. As the second flood set in and the boat began to right herself, we spent three hours with the help of the resort caretaker trying to move her, but as high water came and went so did our hopes.

Despite our extreme fatigue and frustration we were determined that Sea Dragon would not see another low water on the bar, so we begged as much assistance from local boat owners as we could muster, managing four boats, including one with 400hp on her transom.

After some careful co-ordination, Sea Dragon was finally towed to safe water, where we were able to lay the anchor and breathe a momentary sigh of relief. But it was also time to see the crew safely, but sadly, on their way after a truly epic expedition.

It transpired that during our time aground that, despite our diligence, we had neglected to shut the seacock on the main engine exhaust, which meant the engine wouldn’t start. Luckily the full-time skipper and mate of Sea Dragon joined us in Guyana, and after numerous oil changes and a complete service of the injectors, the engine finally restarted undamaged.

The true essence of expedition sailing lies in exploring the unknown, which brings with it a sense of trepidation and discovery, but with hindsight, we could have enlisted the help of a guide for the latter part of our journey into the Essequibo. Isn’t hindsight a wonderful thing?

Emily Caruso is a Yachtmaster Ocean and Yachtmaster instructor who combines freelance teaching with skippering expedition yachts, and has trained many of the participants of the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race.

About Exxpedition and Pangaea Explorations

Sea Dragon’s mission was organised by eXXpedition, a research group founded by accomplished sailor and environmentalist Emily Penn, and environmental scientist Dr Lucy Gilliam. Their goal is to promote awareness of microplastics and toxic particles in our ocean environment by ‘making the unseen seen’, and in turn to encourage women in the sport of sailing and in STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). Emily Penn also cofounded Pangaea Explorations which owns Sea Dragon. By conducting the expeditions from a 72ft sailing boat, the passage distances can be covered while minimising the environmental impact of fuel consumption. For more information, visit: exxpedition.com or www.panexplore.com