A multinational crew made up of pierhead jumpers, family and friends make an eventual voyage from Norway to the Black Sea via Arctic Russia

When the Great Seamanship series was planned back in 2004 it was about giant waves, dismastings, amazing rescues and the like. Research, however, led me into a wonderland of nautical literature with so much to give that discounting it for lack of stormy seas would have been a lost opportunity. Over the years, the result has been a mix of inspiring accounts, some in line with the original brief, others diverging, but all with tales to tell and lessons to be learned.

This article falls into the latter category, because the actual sailing only occurs at the beginning and end of the voyage. The fact those miles are logged off Arctic Russia and through the Sea of Azov is almost by the bye.

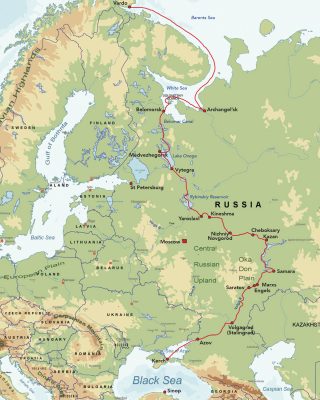

The book in question is Sailing through Russia by John Vallentine and Maxine Maters. In 2013, with crew comprised of a rich variety of pier-head jumpers, friends and family, they take Vallentine’s Formosa 46 Tainui from northern Norway to the Black Sea via the inland waterways of Russia.

Article continues below…

North East Passage ice rescue: Extract from Northabout by Jarlath Cunnane

Jarlath Cunnane’s book Northabout is a must for anyone dreaming of ice navigation or who is fascinated by the history…

A world beneath: Freediving in Northern Norway from a 37ft production boat

It’s below freezing, the wind is blowing 25 knots and we’re in a 2m swell. Barba is dancing over the…

Tainui is the first western yacht to achieve this under her own colours. The Volga leads them far east of Moscow and, despite having their mast on deck for most of the time, the trip remains a captivating adventure. I read the book at a sitting and was very late to bed.

Most of John’s and Maxine’s book appeared first on Vallentine’s blog, but it is now beautifully presented and bound, with noble images. It is half pilot book, half cruising yarn, with both authors and some of the occasional crew contributing to the narrative.

Maxine signed on via a crewing website. She and her skipper considered the risks associated with this and decided to go for it anyway. Her expertise on Russia and its language proved critical to the success of the enterprise. Vallentine is a semi-retired doctor from Australia with a dry, Aussie humour which he really needs, as one crazy nonsense after another gets in his way. He is an unsung hero of ocean sailing.

From Sailing Through Russia

Into the white sea: John

We have 18 hours to go until Archangel’sk, gods willing, and should take our pilot on board tomorrow. The pilot is one of the many bureaucratic burdens we are having to put up with. Reporting in to the Navy and the Russian coastguard every six hours or so by radio, to operators who have no English and are generally unwilling to respond to our calls, has been wearisome.

It has been gloves, beanies, scarves, and three-layer thermals cold. It’s 2°C with wind chill. The Barents Sea is a lonely, grey place and it is good to be into the White Sea. Exactly the same view from the balcony, but psychologically a relief. It has been a long trip from Norway, made worse for me by low-grade, non-vomiting seasickness. Miss Perfect does not suffer from that vile malady, needless to say. Winds on the nose and slow progress.

Maxine had been terrific on navigation and radio communications and is eternally enthusiastic and cheerful. On board she is a bloke, really, and a good one. This afternoon I hove to to reef the main and then flopped into the cockpit for a rest.

Tainui’s mast lowered and stowed on crutches for the passage through Russian canals

Up came Max rugged up to the nines with a bottle of Jacob’s Creek chardonnay under one arm and two glasses in the other hand. A delight, until she started complaining that Tainui’s toilet compartments don’t have under-floor heating.

Still, in bright sun the seas now sparkle and the whitecaps are dancing. It is good to be here.

Solovetsky arrival: Crewman Pasha

We came to the Solovetskiy Islands and enter Blagopoluchnaya Bay. The great walls and domes of the Solovetskiy Monastery are slowly rising from the fog.

Oh, these walls could tell a lot. About builders who hand-laid huge stones in the 14th Century. About the spiritual leaders of the Russian people who lived here.

Oh, these walls could tell a lot. About builders who hand-laid huge stones in the 14th Century. About the spiritual leaders of the Russian people who lived here.

About the heroism of monks who defended the monastery against attack of Norwegian and English fleets in the 18th Century.

About human injustice and cruelty in the 20th Century, when the monastery was turned into a political prison.

But now we want just to sleep. All around is quiet, no person, no sound, only the silent stones of the monastery are watching us.

Finally going to bed, but woken after half an hour by the sound of screams from the wharf. The local guard had slept through our arrival, and now has threats and promises the arrival of a commercial vessel, to which this place belongs. He whines that he is responsible for this place and he would be fired if his boss sees us. OK, we understand. Going elsewhere.

Maxine’s bad hair day: John

It has been difficult. There is too much salt in the bloody Mary, the March flies are too aggressive, the toilet paper is too sandpapery, in Belozyorsk they don’t sell the right cheese, the music’s too loud (Janacek Sinfonietta too loud? For heavens’ sake!), the VHF charger isn’t working properly – there seems no end to it.

She deals with each new March fly in gladiatorial fashion. Her shouted Dutch expletives sound like physio sessions in a TB ward. She seems unable to learn the languid Australian wave, which is just as effective and far less emotionally draining.

I cluck, fuss and coddle. I do my best to appease. I even pretend to like the grits she offers me for breakfast. Nothing works. Then, bless her heart, Maxine apologises for being such a pain. So she should, I think. But I graciously accept her apology and we move on out of White Lake.

Onion domes and minarets on the banks of the Volga

A stately church ruin stands sentinel. We are again alone in our little world. The March flies are few and die bravely for Maxine’s peace of mind. It is warm and there is the gentlest south-east breeze. I think it is great and she reluctantly accepts that the world is a moderately acceptable place.

Madam mellowed later, but punishment is always necessary and she was banished to the foredeck with her bloody Mary to sit in the sun and learn contrition. Alone in the cockpit, I float away.

Female sailors: Maxine

Of course, I knew that sailing in Russia was not developed at all. What I had not realised, though, was a female sailor is an unknown concept for most ordinary Russians, in whose minds boating is strictly for men only. In the north, where sailing is almost unheard of, I found it difficult to establish my authority and competence. Three occasions stand out.

In Vytegra, I had to go climb to the top of the mast before the crane workmen accepted that I was capable of any more than just making coffee.

In one of the Volga-Don locks, a lock-keeper thought that there were no males on board and remarked on the fact over the radio. I asked him whether he thought that mattered. He giggled and did not know how to reply.

In the Sea of Azov, negotiating our way into Kerch, I had to provide the port authorities with crew details by radio. When I told them there were two people on board, the skipper and the first mate, they then asked who I was! They did apologise though, when I gave them an earful.

That being said, these episodes were only a minor irritation, never a real problem. Once we got south into sailing territory most people we dealt with were sailors. Even if they were male, they were emancipated.

Impressive lock entrances on the Russian inland waterways

Sviyazhsk: John

This morning I got up at 5am to watch sunrise. Tainui is anchored meekly in the lee of Sviyazhsk Monastery. It is a beautiful, cold, clear morning with drifting fog banks. The onion domes loom silent, imperious, with a full moon and mist on the water adding needless extra theatre. Sviyahzhsk is a remarkable collection of buildings dating back to 1600, with that familiar history of Bolshevik sacking, gulag prison, psychiatric hospital and now, finally, treasured archive.

Happy hour last night was extended by the skipper’s indulgence (starting time noon, closing time 10pm) because we had passed the halfway mark in our Russian journey. Inexplicably clumsy, one of us spilled a bag of crisps in the cockpit.

There is no need to mention the two glasses of red wine that might have been kicked over during the same session. So this morning I lifted the teak grates to sweep up the mess while the girls sat by, sipped coffee and gave useless advice.

The best thing about having Dutch people on board is that, carefully managed, their deep-rooted compulsiveness can be exploited usefully. And so it was this morning. Our new crew Lieve (she’s actually Flemish, not Dutch, but, hey) felt she had no choice but to take control of the cleaning process. With the grates up, an intense, noisy and endless process of Flemish surgical sterilisation has begun. Wisely, I retreated below.

John as second fiddle: Maxine

Poor John! A skipper with so many years of sailing experience, totally used to running his own boat, managed to get this woman on board who is not used to playing second fiddle, not used to translating every word being said, explaining every step being taken – someone who is more used to getting things done, conveying the results, then expecting them to be accepted without discussion.

John’s usual crew had always had English as their first language. It took me a while to realise that he had never sailed before with someone he found through a crewing website, someone whose first language was not English. Whose background was not Australian or even Anglo-Saxon. And he’d never sailed with someone who could speak the local language in non-English speaking countries.

So John had to get used to someone from a culture he did not know, who instantly took over all negotiations regarding the boat and failed miserably to keep him updated at each step.

Culture clashes one way or another happened all the time, – not only between us, but between John and Russia, where a simple question to a local, which technically could be answered with a yes or no, would always be followed by an endless discussion. This would drive John absolutely desperate. In Saratov he retired to the foredeck to sulk. I often found it easier to exclude him – I really didn’t want to have to translate and explain everything at the same time.

Looking back, it’s just astonishing that the two of us managed so well together. But there was commitment, focus, in nite mutual trust and perhaps, most important, a shared love for this unique journey.

Sailors and authors Maxine Maters and John Vallentine

Man overboard: John

One of the more testing jobs I have each day is choosing the title for the web post.

Today’s choice was easy. I was enjoying an ale in the cockpit in celebration of something or other, while Maxine was hosing mud off the foredeck. Suddenly the hose nozzle burst from the hose and went over the side. Before I could put down my ale, Maxine had stripped off and dived in after it. With not so much as a ‘by your leave’.

Never mind the 25 knot following wind and the associated chop. It was left to me to disconnect the autopilot, find somewhere to put my glass of beer, execute a Williamson turn, prepare the boarding ladder, heave to upwind and manage the controlled drift down to her. It was a textbook man overboard recovery.

Now I am finishing my ale while the deck continues its ablutions. And Maxine? Well, I’m not sure about her, but that nozzle was a vital piece of equipment.

Sea of Azov: John

The short stretch of the Don below Azov is just as beautiful as the waterway above it.

Looking back at Azov as we motored downriver I was sad to be saying goodbye. Needless to say, we cracked a bottle of chardonnay at the river mouth and solemnly saluted. There is a 20-mile long, very narrow dredged channel from there out to sea. It is well buoyed but not wider than 30m, at times less. The depths are 1m or less on each side. Ships pass with difficulty.

It was in mid-channel that our salt water inlet suddenly became blocked with weed. Maxine announced that a large bulk carrier was approaching through the gloom of the dusk. She called it up to warn we were NUC (not under command) while I scrambled to clear the hoses and somehow we got to the side of the channel to allow the oncoming ship to pass.

The 200-mile passage Azov to Kerch’ in Ukraine is divided into two equal parts. The first leg was a gentle square run with everything poled out, warm sun, good food and wine. An endless parade of ships passed us to starboard.

With a splendid sunset we dropped the pole, rounded the corner and turned south to Kerch’. Under starry skies and with a freshening breeze, Tainui danced through phosphorescent seas with a bone in her teeth. All night we rushed south with a steady beam wind. Dawn brought relief from the constant vigilance required by the huge volume of commercial traffic, but we are both buggered. To put it mildly.

First published in the August 2018 issue of Yachting World.

Sailing through Russia: From the Arctic to the Black Sea by John Vallentine and Maxine Maters is available via Amazon, RRP: £24.95.