Yachting World's Toby Hodges sails the radical new ClubSwan 125 Skorpios and gives you a tour. Skorpios is the largest entrant in the Fastnet ever and took line honours weeks after launch in 2021

It’s tricky to gauge speed and scale against anything else when you have to sail a few miles offshore to avoid dredging the English Channel. Nevertheless, sailing onboard the new ClubSwan 125, I could tell that great stretches of the UK’s coastline, passages that would normally drag by over hours, were ripping past at a velocity that made me question my knowledge of known landmarks.

Aboard Skorpios, the imposing new ClubSwan 125, we’re not talking outright silly peak speeds, but more the sheer unrelenting consistency of the high speeds. At 140ft including bowsprit, Skorpios is, by any scale, a beast which, under its substantial sail area, becomes an uncompromising, fiendishly powerful mile-muncher.

Standing at the windward helm when powered up feels so high above the water it’s akin to leaning out of a second storey window. And with over 20 top professional crew sitting on the rail in front of you it is an awesome, slightly terrifying and utterly captivating experience.

However, this is not a Swan built for helming pleasure, rather with a ruthless brief to be the first monohull home in the big offshore races and to rewrite ocean records.

Skorpios is skippered by the Spanish Olympic Tornado gold medallist Fernando Echávarri, a former Volvo Ocean Race skipper.

The adrenalin of sailing the ClubSwan 125 Skorpios is perhaps heightened by the fear of the unknown: everything about this yacht seems to be on another scale altogether. This is, by some margin, the biggest offshore racing monohull, and certainly the largest ever racing Swan. It boasts possibly the deepest draught non-lifting keel (7.4m) and the largest sailplan combination ever conceived. In short, Skorpios is a seemingly limitless source of superlatives.

Skorpios is the largest monohull to have raced in the Fastnet Race to date, and, as its designer Juan Kouyoumdjian pointed out with a certain glee, it has been issued with the highest IRC rating ever awarded.

Not that handicaps will be of concern – it’s out for line honours only. That it duly succeeded at such a task at the first time of asking is all the more impressive considering the gun for this year’s particularly boisterous Fastnet start was fired just two months after the boat splashed.

This was also the first offshore race for the yacht’s owner Dmitry Rybolovlev. Sometimes it takes an ambitious owner with a substantial chequebook to make a meaningful step forward in design and engineering, and produce a ripple effect in technology.

In the case of ClubSwan 125 Skorpios it was Russian businessman and philanthropist Rybolovlev who fell for the idea of a record breaker after tasting racing victory on his ClubSwan 50. The contract was signed in February 2017 and, four years and a pandemic later, his near three times larger version was wheeled out of Nautor’s famous Pietarsaari yard.

Just a month after its June launch, and during an intense work up period before the Fastnet, I was invited to join Skorpios for a day’s race training.

Science project

The isle of Portland is one of the few safe ports around the English Channel with a deep enough berth for Skorpios. From Dorset’s Jurassic Coast cliffs miles to the west, a single mast stands out on the horizon and as I approach through the commercial dockyard, the scale of Skorpios seems to keep increasing. It’s simply enormous, unlike any other yacht I have seen.

Enough sail? Skorpios off the Dorset coast. The ClubSwan 125 is named after owner Rybolovlev’s famous Greek island, where Jackie Kennedy married Aristotle Onassis. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

Testing systems and sea trialling for race prep takes a significant amount of sea room on a craft of this size. Thankfully we have ideal 17-22 knot conditions to encourage a long day afloat.

“We’re going to stay two to three miles offshore and sail down to the Isle of Wight,” Fernando Echávarri announces to the crew. The quietly spoken team skipper, a Spanish Olympic Tornado champion, assembled a crack team around him during the build and seems to have the unflappable composure needed for such an endeavour.

Article continues below…

Canova – The foiling superyacht designed for comfort

Were you to somehow be teleported into foiling superyacht, Canova’s palatial master cabin while under way – and let’s face…

Video: Comanche – Matthew Sheahan gets aboard the world’s fastest monohull

Setting the start line ends in your chart plotter two days before the race may seem a little over eager,…

I crane my neck as 660m2 of black 3Di mainsail is hoisted up a mast that scales 59m from the waterline, high enough for the enormous 5.5m gaff of the squaretop to be in a totally different weather system.

“This boat’s a real science project,” says Miles Seddon, reading my mind as he joins me on the aft quarter rail. The British pro navigator has stepped aboard to give some local knowledge during the Fastnet build-up.

“There are so many systems, load sensors, fibre optics etc all trying to integrate… and all are logged at 10Hz so everyone can monitor it (aboard and ashore).”

The giant ClubSwan always sails heeled and the apparent wind never really goes aft of 80º. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

With loads too high for human power onboard the ClubSwan 125, the grunt is all left to hydraulic pumps to drive winches and movable appendages. Hence the ability to monitor all loads constantly is reassuring and educational.

Nevertheless, I recognise many of the faces of the international crew who have amassed dozens of America’s Cup, Volvo Ocean Race and Olympic wins between them. The size of this craft and its level of tech places it in a high-risk category, so the ability to sail this ‘project’ safely and to the optimum, particularly with such a short training period, requires all their skill and experience.

Key crewmembers talk sporadically through their headsets, which are covered by neck scarves to try to protect against apparent winds that are typically gale force. It’s all coded language, acronyms and target talk – we are in test pilot territory here.

thrill of a lifetime as YW’s Toby Hodges gets behind the wheel. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

As 1,300m2 of A3 (asymmetric spinnaker) is unfurled we accelerate from a 10 knot canter straight to the high teens. Then out come the J4 (jib) and IRS – the bright orange sail which rates as a storm jib – to fill the large slots and Skorpios is immediately into the 20s.

I record the angles and speeds throughout the day and, looking through these later, it’s their consistency at which I marvel. “We are sailing with nearly 2,400m2 in a 59-tonne boat – so it’s pretty powerful!” Echávarri remarks. Indeed the sail area to displacement ratio of 67.8 is mind boggling.

50% Movable ballast

“Designing a racing sailboat, able to reach a speed in the region of 15 knots upwind and that will always be faster than the wind speed downwind is something unique,” comments Juan K.

The Argentinian designer, who was aboard for our trial, explains that he chose a canting keel in order to keep the displacement under 60 tonnes, which allowed for the necessary righting moment with a smaller bulb.

However, this was not always the plan. The ClubSwan 125 was originally conceived by Nautor as more as a performance cruiser-racer with teak decks and a full interior.

The decision to remove these saved an estimated six tonnes immediately. And once the owner said he wanted to go really fast, the design was continually re-evaluated. The original keel proposal was a complex telescopic/canting mechanism, so replacing that saved another 2.5 tonnes. The interior was also adapted, designed by Adriana Monk to be very minimalist and practical for offshore sailing.

The canting angle of the keel increased from 38° to 42° and a trim tab was added. The potential lift and righting moment benefits this can give were one of the areas the crew were looking at during our sail.

sailing triple-headed makes for a lot of halyard tails and sheets to keep tidy. The smart dodger was a late addition, for protection and to keep the companionway dry. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

“With a canting keel you need another appendage to produce the required side force. That is provided here by a C-foil, a hydrodynamic asymmetrical foil, but symmetrical from port to starboard, that can be tacked each side of the boat,” Juan K explains.

He estimates that this is less weight than two daggerboards and can help the boat reach a ‘skimming’ attitude when reaching. “It doesn’t give you the performance of side foils, but without the C-foil there would be 5-7° leeway. With the foil, there is zero or even negative leeway with the keel canted.”

Then there is also the equivalent weight of an average 40ft cruising yacht in water ballast, housed in 5,000lt and 3,000lt tanks each side. These take 45 seconds to fill and 30 seconds to transfer from one side to another.

“It’s righting moment without the weight in light airs,” Juan K elaborates. When more than half the weight of the boat can be shifted from side to side, pushing the correct buttons becomes imperative.

After a couple of hours in downwind mode, we’re now somewhere south of the Island and furl to gybe. An army of muscle manhandles the trunk of furled A3 onto the deck and into a bag so it can be lifted by halyard and deposited across the aft deck in preparation for the first upwind leg.

It is while briefly parked like this that the alien noises, reverberations and discomfort start. Every element of this craft is designed around speed, so restrained like this, the giant Skorpios groans and shudders like a tethered animal and the raw vibrations are felt right through to the aft deck.

ClubSwan 125 weight and windage

We’re given a steady 20 knots true for our first beat, which is on the limit of a reef in this sea state. Yet with or without a reef, we still average 14 knots at 25° to the apparent wind.

The single C-shape daggerboard is moved hydraulically from side to side to negate leeway and when fully retracted still sticks out by 80-90cm. Sensors continually inform the crew about the loads on the board. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

The harmony of the rig and sail package on the ClubSwan 125 is impressive. Southern Spars designed the high modulus mast, 60ft boom and 23ft reaching strut in combination with sister company North Sails and its Helix structured luff technology. The company says it’s one of the most advanced rig packages it has ever delivered.

The tack points were originally designed to take much higher loads, but the advances in structural luff technology and load sharing means that these point loads have greatly reduced, project manager Bob Wylie tells me. “The J2 was originally designed for 45 tonnes, yet the current tack load is around 25 tonnes.”

Future Fibres’ Aerosix rigging minimises windage. “Considering the speeds and the close apparent wind angles you’re sailing at, everything contributes to speed,” comments Echávarri, who is most impressed with the comparative reduction in vibration this rigging brings.

The highly raked mast can be finely tuned with checkstay and backstay deflectors. “To set all the sails needs a bit of play between the mainsheet trimmer and the runner trimmer,” Echávarri explains.

“The J0, which is tacked to the bowsprit, is 550m2. So with the 660m2 main we can go upwind with about 1,200m2, which is a big load!” the skipper exclaims. Occasionally we slam through or over a wave and the vibration is gut wrenching.

Otherwise, however, it’s comparatively quiet speed sailing, with hardly any noticeable wake, just the firehose of a rooster tail spraying from the stern as Skorpios planes along continuously like a giant 49er.

Twin rudders are used for control as Skorpios always sails heeled. These have Juan-K’s trademark sawtooth profile which he compares to the tubercles of a whale. They are designed to limit drag when dipping in and out of the water and to prevent the blades from stalling.

The toe-in system, which changes the angle of attack of the rudders, is adjusted from on deck using a geared system first developed for the VO70 Groupama. “You want the windward one to have the least drag,” Juan K explains. “For downwind VMG sailing we’re looking at 11-15° heel, reaching is 20-25° and upwind is 25°. At around 21° the windward rudder stops touching the water – it’s ideal when it’s just kissing the water.”

Life at heel

While you are certainly aware of the near 30ft of beam when sailing upwind on the ClubSwan 125, it doesn’t feel like alarming levels of heel. Skorpios tracks along on its chine, while on deck the SeaDek closed cell foam decking provides excellent grip and the aft companionway and mainsheet plinth help to break up the large cockpit spaces.

The deck design is remarkably uncluttered and kept deliberately simple, meaning minimal winches and lines on deck. The use of multiple furling foresails, similar to a racing multihull or IMOCA 60, helps simplify manoeuvres. One of the neatest features is having the furler lines all lead under deck.

Sailing Skorpios requires the balancing of phenomenal sail area with moveable ballast and righting moment, while keeping the boat on a narrow (heeled) waterline beam. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

“They have to be,” comments Wylie, “imagine a 450kg sail sitting on them – they wouldn’t shift!”

A keyboard of constrictor clutches are also used under the deck and the headsails are all on halyard locks, as are the three mainsail reefs. Lights and alarms display when these locks are engaged and then there are sensors everywhere, says Echávarri – “in the hydraulics, linear sensors between cables and sails, on vertical shrouds, on winches etc.”

During our second uphill leg I spend some time at the forward end of the rail’s crew stack filming and getting duly soaked. It really hits home how relentless and potentially exhausting it is sailing in such high apparent winds. It’s little wonder IMOCAs and Ultimes have dramatically increased their protection and aero packages.

Meanwhile, out to windward the chase boat bounces along with photographer Mark Lloyd aboard trying to steady himself. Not many powerboats could keep up with the ClubSwan 125 Skorpios in these seas, but this is no ordinary tender. Theirs is a 15m carbon catamaran, complete with 1,200hp of outboard propulsion, which was built in New Zealand in parallel development with Skorpios.

“When we decided to go lighter and lighter, the anchor became a big factor,” Echávarri elaborates. With a 7.4m deep keel, Skorpios will have to rely on its anchor gear, so the tender was designed to carry and deploy the main anchor and 600kg of chain. And because of the mothership’s restrictive draught, this chase boat also has the tanks to fuel bunker, while a sawn-off bow allows it to nudge up to the transom to unload supplies and swap sails. The sheer scale of this project!

The buzz

And then it happened… one of life’s golden moments. I am offered a glory spell on the wheel. We are smoking along, sheets ever so slightly cracked, making a steady 15-16 knots in 18 knots of breeze and Skorpios is like a freight train, unwavering in its speed and line.

Occasionally I glance the long way down to the leeward rail and see the whitewater shooting past. It makes me giddy. Concentrate on the numbers Toby, this is no time to lose focus.

Minimalist saloon with canting furniture. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

So much power is felt through that foam-gripped composite wheel. On the pedestals are a hydraulics cut-off, a Jonbuoy release button, a high load alarm, and controls for the canting keel and trim tab. Needless to say I keep my hands on the wheel. The sheets are left alone as we charge back towards Portland, full steam, while I try to log every second in my long-term memory bank.

When the decorated Olympic and round the world sailor Xavi Fernandez turns round from the rail and asks me how it feels on the helm, I am lost for words and simply grin.

Echávarri sums up our sail more casually; he’s concerned with stats not emotion. “Today was a good day. Let’s say we were pretty good in performance – 95-98% of VPPs, which is good when there’s still a lot to learn.”

I simply tremble with nervous adrenaline… for days.

Building a beast

“The opportunity to work together with the greatest boatbuilders, designers and technicians around the globe, was awe-inspiring,” says Leonardo Ferragamo, Nautor’s Group president. Nautor’s Swan conceived and built the yacht in Finland, but with so many teams and subcontractors involved, Skorpios is more a custom race boat than a conventional Swan.

“A team of 30 was initially brought in to laminate the hull,” says Bob Wylie, while explaining the challenge of maintaining a workforce during Covid times. Grand-Prix raceboat construction techniques were used, including unidirectional prepregs and honeycomb nomex cores, with monolithic construction below the chine.

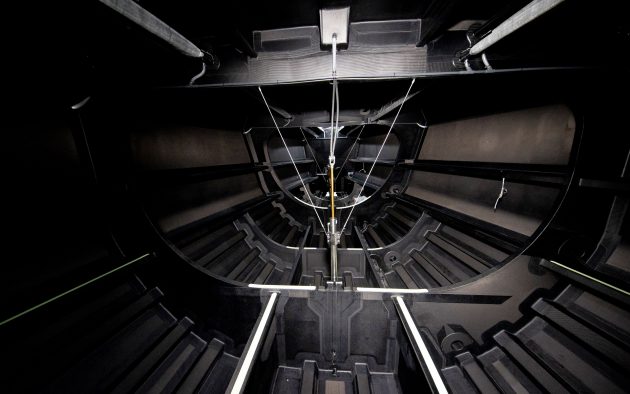

engine room contains the twin 400lt carbon hydraulic tanks and the mast base (mast jack load at full dock tune is around 90 tonnes!). Otherwise it’s just an engine and a spare genset, but no domestic batteries, chargers or inverters. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

Post sailing we have a chance to look below decks of the ClubSwan 125 and it’s way more Spartan than I had been expecting. There is some cabin comfort for overnight races and a focus on safety in the saloon for guests. That’s it.

“As you get faster and faster you start to think of the security on board,” Echávarri explains. “We developed a super light, safe interior which is minimalist and nice looking.” The saloon seats rotate over a central hinge to suit the heeling angle and the table cants at multiple angles on titanium hinges. The ‘galley’ is a gimballed microwave on a central bulkhead unit with fridge below (“this is all we allow them,” Echávarri grins). Otherwise it’s just pipe cot-style bunks each side of the saloon and a day heads/shower.

The forepeak is known as the cathedral for its exhibition of bare structures, stringers, bulkheads and longitudinals. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

The minimalist nature encourages you to focus on the build and finish quality, which is quite remarkable. A closer look at the bulkheads and doors reveals they are all bare carbon. Bar the deckheads and sole panels there are no liners, no panels, not even a drop of paint. It really is a Formula One shell built and finished with Nautor quality.

Move forward from the saloon and you won’t find any of the luxury cabins or accommodation you might expect on a large Swan, just a bare central engine room, the foil casing and acres of the black stuff. See for yourself on our walkthrough video on yachtingworld.com

What’s the goal?

“At the moment the challenges are the races – the Fastnet, the Middle Sea Race,” says Echávarri. “And slowly we will see the real potential. The concept didn’t start with a record breaker brief and we don’t know if it will be faster than Comanche yet. If we feel like it has the potential, we would like the north Atlantic.”

Whether speed is best measured for you on a Moth, SailRocket, an Ultime trimaran or this goliath, those who push for line honours and records will always make headlines. The ClubSwan 125 could potentially set a new bar in that respect. And by taking line honours in its first event, Skorpios has already proved it’s got the necessary sting in its tail.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.