No longer science fiction, virtual reality is more than mere entertainment. It can be used for sailing instruction too, says Toby Hodges

Virtual reality (VR), a term once reserved for science fiction movies, is now a commonplace reality for techies, film buffs and video gamers. VR uses computers to create a simulated 3D immersive world that you can manipulate. When immersed in it, you become unaware of your real surroundings.

Like it or abhor the very concept of it, VR is becoming a technology that is increasingly hard to ignore – the technology giant Samsung is already issuing free VR headsets with its new S7 mobile phone, for instance.

But is this simply the next gaming fad, or is there potential for it to benefit our sport? The America’s Cup teams at the élite end of racing have employed VR for shoreside training since the 2013 Cup.

However, with the launch of some new VR apps aimed at leisure users, we are interested in how this technology might be relevant to mainstream sailing.

During an IBM creative workshop I attended recently, one of the key areas identified as potentially better serving our audience was the use of VR for the education and enjoyment of sports such as sailing.

Getting afloat is not always easy to achieve, not least because of time or location. To be able to visualise the look and layout of a moving yacht via a headset could provide a useful training platform as well as another form of sailing-based escapism.

A crucial benefit of VR is that the user matters – it’s not simply a sideline experience – so the potential of using it for instruction is potent. It’s certainly not for all, though. Visualising movement on such immersive headsets is known to cause discomfort. Simply using VR to tour a new yacht’s interior made me feel quite nauseous. VR is, however, here to stay.

New apps for sailing

The big budget racing teams in the America’s Cup have already tapped into the combined VR and simulator technology employed by the aircraft and motorsport industries. Even the Duchess of Cambridge was pictured last year trying out VR sailing technology at the BAR base with Sir Ben Ainslie.

But a new company in Australia has stolen a march on off-the-shelf VR, bringing sailing apps to mainstream sailors.

Melbourne-based MarineVerse was founded at the start of the year by Greg and Olga Dziemidowicz.

Greg Dziemidowicz thinks VR can be used to offer both sail training and entertainment. “I believe virtual reality can greatly enhance sailing training, be a great way for all ‘landlocked’ sailors to stay connected to their hobby and introduce more people to sailing,” he says.

Dziemidowicz believes VR allows people to learn more quickly and economically. “VR enables us to provide sail training and education at your home. It’s a fun and engaging tool to reinforce what you are already learning on the water.”

For instance, a liferaft drill can be practised using VR, as can operating a distress flare. “Or we can walk someone through a process of setting up a spinnaker.”

“VR can offer a great feeling of immersion, making the experience very engaging,” Dziemidowicz continues. “You can develop spatial awareness and intuition.” Or in my case, you may experience lifelike symptoms of seasickness.

MarineVerse is currently building VR sailing applications for Google Cardboard, GearVR and HTC Vive. So far it has released more than six prototypes, some focused on teaching sailing, others on the actual sailing experience.

Most recently MarineVerse has created a sailing simulator and an educational i-learning app called Sailing Terms, which uses the new HTC Vive platform – a high-end head-mounted display with hand-tracking controllers. This combination allows the operator to use their hands to control functions such as the mainsail and tiller.

“Using HTC Vive is quite exciting, as it’s the most immersive solution currently available,” Dziemidowicz says. “Because HTC Vive tracks your position in the room, you can actually lean forward and inspect elements from a closer distance.”

MarineVerse apps and games are all free while the company is still in the early access stage. www.marineverse.com

America’s Cup simulation

On-water time is crucial but limited for Cup teams. The BAR team’s Portsmouth base means testing days are often also limited by the weather. So a full-size moving simulator was constructed to help the helmsman and wing trimmer develop their relationship.

The cockpit simulated platform moves on a series of hydraulically actuated legs, in the same way as an aircraft or F1 simulator, while helmsman and trimmer wear VR headsets.

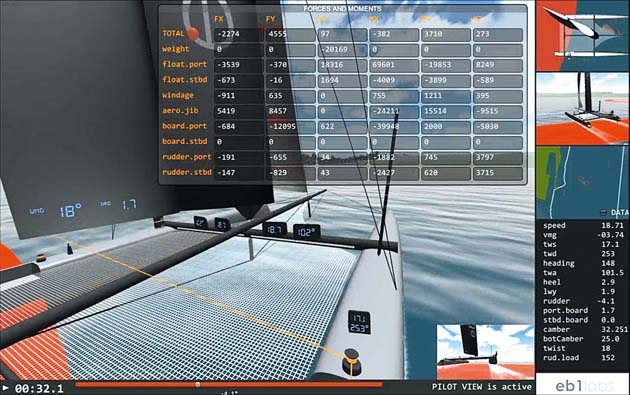

Following the successful 2013 Cup, the eb1 team, which worked for Oracle Team USA, built driRun, the world’s first professional grade virtual sailing simulator. ‘On 16 October 2012 the US$20 million Oracle Team USA catamaran capsized on San Francisco Bay and was destroyed,’ says its literature.

The subsequent four-month rebuild was a forced lay-off that ‘painfully illustrated that the world of high-performance sailing has become incredibly dependent on empirical testing and full-scale prototyping which can be dangerous, expensive and inefficient.’

While this technology may still be way in advance of the needs and skills of most sailors, the America’s Cup consistently leads the way in providing trickledown technology. See www.eb1labs.com for more.

VR today – hardware

Consumer-ready virtual reality technology is already widely available. The main players are Oculus – a Kickstarter-funded company that sold to Facebook for US$2bn within two years of its 2012 start-up – plus Sony, HTC, Samsung and Google.

Google Cardboard has proved to be a clever marketing tool to get the technology out to the masses – today’s version of the 3D paper cinema glasses of the 1950s if you like. More than five million Cardboard devices had already been shipped by the start of 2016.

The PlayStation VR comes out later this year. And don’t be surprised to see Apple push into the VR sector soon. Motherboard, an online technology magazine reported that: ‘Revenue from virtual reality hardware and content will reach almost $22 billion worldwide in 2020, compared with only $110 million in 2014.’

Growth is predicted to continue to accelerate rapidly as the hardware comes down in price. Current VR devices are still relatively expensive, which helps explain why the mobile phone-based VR headsets are becoming increasingly popular – everyone already has their own portable display.

Samsung’s Gear VR, which launched in November 2015, is far cheaper than the PC competition. Meanwhile, Google Cardboard sets are often given away in promotions.

Prices: Oculus Rift US$599 and HTC Vive $799 plus the PC hardware needed. Samsung Gear VR US$100. Google Cardboard $14.99.

Marineverse VR apps

Point of Sail was the first app MarineVerse made. “It teaches basic sailing concepts using visual cues and voice,” explains Greg Dziemidowicz. “It takes advantage of VR, by letting you look around and putting the knowledge in context”

Sail to Freedom is a VR sailing game where the user attempts to cross the Baltic on a small yacht. It allows you to sail the boat from a first and third person perspective

VR Regatta is a racing game for GearVR and HTC Vive. “Our plans are to make it fun to play for sailors and those curious about sailing. Already you can sail around the track and measure your performance”

What is virtual reality?

VR headsets require a computer or smartphone to run the app or game. The headset brings the display to your eyes either via a video link from the computer or, more simply, by using the phone’s display. A method of control input is also needed, by hand, voice or trackpad – or the device tracks head/eye movements.

VR headsets tend to use head tracking to enable the picture to shift with your head movement. These work by measuring the pitch, yaw and roll of your head. Lenses in a headset can reshape the picture for each eye to create a 3D image. They can increase our normal field of vision, which helps users feel immersed in the virtual world.

And it is that feeling that is the ultimate goal of VR – making the experience so real that we forget about the accessories and the world outside.