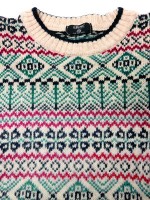

Heading for the tiny, remote Scottish island of Fair Isle to pick up his hand-knitted sweater, Leon Schulz found it much like living on a boat – no wonder he felt so at home

The sweaters are now imitated to such an extent that ‘Fair Isle’ could mean many forms of colourful sweater. The island itself, however, remains unique; it is only here that the original hand-framed and hand-finished woollen masterpieces are made in the traditional way.

I decided I’d like to become the proud owner of a real Fair Isle and collect it in person by sailing to the tiny island, situated where the Atlantic meets the North Sea. It turned out that I had to sail there twice: the first year, I found out that the sweaters are made to order and they were unfortunately sold out a year in advance. I took this as an opportunity to leave my measurements and plan another voyage. My sweater became number 18 out of 20 made that winter and is worth every stitch of the £200 it cost.

I decided I’d like to become the proud owner of a real Fair Isle and collect it in person by sailing to the tiny island, situated where the Atlantic meets the North Sea. It turned out that I had to sail there twice: the first year, I found out that the sweaters are made to order and they were unfortunately sold out a year in advance. I took this as an opportunity to leave my measurements and plan another voyage. My sweater became number 18 out of 20 made that winter and is worth every stitch of the £200 it cost.

The first time I came from the north like the Vikings used to, crossing the North Sea from Norway to Lerwick on Shetland. From Lerwick it was a short 40-mile leg south to Fair Isle. No sooner had we found our way into the narrow entrance between the rocks, than fog and darkness closed the door behind us. Any attempt to exit or enter had become impossible. It was strangely quiet in the bay, as so often in fog. The only boat in the harbour, we moored alongside the concrete pier, knowing that no other boat would dare to enter. Had we come to the end of the world? It felt like a mystical place, for sure.

A safe haven

The following summer I came from the south, sailing through the English Channel and north via Ireland and the Hebrides. In the face of relentless gales with storm force winds that had been predominant during the entire season, I chose to avoid the notorious Cape Wrath on the north-west corner of Scotland and opted for the calm and comfort of the Caledonian Canal, enjoying a sunny trip through the heart of the Highlands instead.

From Inverness it was a day’s sail north to Wick, the last outpost on mainland Scotland. I crossed the Pentland Firth to Kirkwall in Orkney and reached Fair Isle on the third day after leaving the canal.

Fair Isle has only one properly safe harbour, North Haven. South Haven, which looks tempting in northerly winds, is not advisable owing to a rocky bottom with poor holding. The third harbour on Fair Isle, called South Harbour, is foul with rocks and must be approached with extreme caution.

Fair Isle has only one properly safe harbour, North Haven. South Haven, which looks tempting in northerly winds, is not advisable owing to a rocky bottom with poor holding. The third harbour on Fair Isle, called South Harbour, is foul with rocks and must be approached with extreme caution.

So, if swell and weather makes the entrance to North Haven impossible, sailors must be prepared to do as the cruise ship did when we first tried to visit Fair Isle: it just went on and left Fair Isle to its usual tranquillity.

Great expectations

With great expectations and much better weather this time, we entered the North Haven, as we had done the previous summer, holding the conspicuous rock that forms part of the breakwater in transit with the hill called Sheep Rock in the far distance.

Once inside the natural harbour we were surprised to see so many boats all flying different ensigns: UK, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands and even Switzerland! We moored alongside a beautiful 1936-built wooden Norwegian gaffer and astern of the HR40, Regina, which I had once owned and sailed to the Caribbean. What coincidence, chancing upon my old boat in this remote place. She is owned by a Swiss couple on their way round the world.

No sooner had we moored Regina Laska than my Fair Isle knitter, Hollie, turned up in her 1980s car, which had not passed its MOT on the mainland and which, as a result, she had been given as a gift from a friend in Shetland. It had been lifted by crane onto the small deck of Good Shepherd IV, which the islanders call The Ferry, and shipped over to Fair Isle.

You don’t need an MOT on Fair Isle. The car serves Hollie for transport on the only road there is, stretching from the southernmost end of the island, where most of the 57 inhabitants live, to the harbour with the adjacent bird observatory, lying some four kilometres to the north.

“It would have been a shame to scrap it, don’t you think, Leon?” Hollie greeted me from the pier. We hadn’t met for a year and yet it felt as if we were old friends, who had been parted for only a week or so.

“As long as I can brake in front of all the sheep, there is nothing wrong with this car!”

Hollie pointed out the many lambs that are too young to understand that the road had not been built for them and that it would be wiser to give way to the few cars there are on the island.

The sheep here are of a very special island breed called Shetland sheep, which can withstand the harsh environment. I wondered if the people were of a similarly special breed to live here on this rock on the edge of the Atlantic.

The sheep here are of a very special island breed called Shetland sheep, which can withstand the harsh environment. I wondered if the people were of a similarly special breed to live here on this rock on the edge of the Atlantic.

Just like liveaboards

It’s difficult to explain why I have fallen in love with Fair Isle, but I think it is a combination of the nature, the colours, the people and the mystical atmosphere. Anyone who has been here once most likely wants to return. Some even decide to stay for good. Nobody I have spoken to living on Fair Isle today can imagine moving away. It is an easy island to fall in love with.

The lifestyle is probably not unlike living on a cruising boat, after all. There seem to be many similarities between sailors, liveaboards and islanders. The inhabitants of Fair Isle may seem to live an alternative life compared with city people, but they do not regard themselves as ‘alternative’. They demand the same modern amenities as their mainland cousins, but prioritise the luxury of living a free and simple life in a small community with low expenses. And do we not all share the same thoughts when we move on board, living on our own boats?

There is a school on the island, a nurse, a shop, internet connection, electrical power, water and even a small museum. What else do you need for a simple, happy life? The Good Shepherd IV sails to Shetland three times a week during the summer and once a week in the winter, taking a maximum of 12 passengers – weather permitting.

For instance, Hollie could not get to her grandmother’s funeral because of fog and even the small aircraft could not take off from the grass strip in the middle of the island. When this happens, there is nothing to do other than to bring out the instruments that most islanders seem to play, especially the fiddle, sit in front of the peat fire and leave the dark days of winter outside.

At 2330 each night the power is switched off, when the diesel generators have done their duty for the day. Power was, by the way, introduced to Fair Isle as late as the 1960s.

If a gale is whistling around the doors, you might be lucky in that the wind generators continue to produce power – if they are not broken down, that is, which has been the case since January.