Here are our top expert tips on sailing back across the Atlantic to Europe after a season in the Caribbean or the US East Coast

Sailing from Europe to the Caribbean is the downhill ride. With its promise of following winds, warm seas and an exotic destination it’s the ocean crossing of which sailors dream.

But sooner or later the time will come to return. The way back from the Caribbean to Europe is not so welcome. The weather patterns are much less predictable, the days and nights will be getting progressively colder and life on board is harder and more tiring. Unsurprisingly, it can also be more difficult to find willing and experienced crew.

But there are ways of avoiding the potholes along the way and make the ride home easier. Here I outline some of the top pieces of advice I’ve heard from skippers on the ARC Europe rally or been given about the west-east Atlantic crossing:

1. Choose the right route

When and where to cross the Atlantic from the Caribbean is the first and biggest decision to take. Two indispensable publications are Jimmy Cornell’s World Cruising Routes and the North Atlantic Passage Chart 100.

Weather systems spinning off the US East Coast bring lows and frontal systems that can extend well south and at some point a yacht on the west to east crossing will be overtaken by at least one front, possibly more. So the aim is to catch and ride favourable winds for as far as possible, and most boats head for the Azores to make a stop there and then pick their timing to head on to Spain or Portugal or north to the UK.

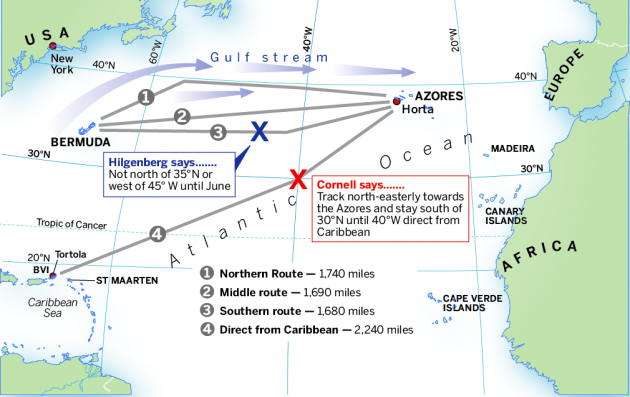

According to Cornell, as early as March and as late as mid-May there are reasonable chances of favourable south-easterly and south-westerly winds on leaving the Eastern Caribbean. The advice he offers is to track north-easterly towards the Azores and stay south of 30°N until 40°W.

Tortola in the British Virgin Islands or St Maarten are the most popular starting points – they are well positioned and good for provisioning, spares and repairs. But many crews make an inter-mediate stop in Bermuda. The ARC Europe crews really enjoyed their visit. Cornell notes that making the diversion to Bermuda is a good option if the wind patterns change three to four days out from the Caribbean.

Someone who has probably the most comprehensive overview of North Atlantic weather over 25 years is former SSB radio net controller and weather forecaster Herb Hilgenberg who, until he retired in 2013, operated a free forecasting and routeing service to cruisers as Southbound II.

The theory is that the low pressure systems tend to lie further south earlier in the season and if you go north you end up north of the Azores in headwinds. The more you move towards summer, the further north the lows lie and the bigger the Azores High so that you get lighter winds as you make your way towards the Azores. In July, some people might even be able to head straight to the UK.

For that reason, Hilgenberg says the best time to leave the Caribbean or Bermuda is May or June “or even early July if there are no developing tropical waves or hurricanes”.

Larger yachts and those with bigger crews may wish to go further north for a faster crossing – see the range of tracks taken by ARC Europe yachts (above). Bear in mind the average boat size on the rally was 47ft.

Hilgenberg tends to be cautious. “I advocate the southerly route to the Azores. I recommend that boats head east and stay south of 35°N until I see that nothing significant is developing,” he says. “You can stay at 32-33°N until a few days out from the Azores and then head north. I would not go north of the area north of 35°N or west of 45°W until June.”

The disadvantage of the southerly route is that it can shade into the Azores High and yachts can run out of wind. This is why some skippers shape a faster, marginally more northerly route or even alter course midway to edge into stronger winds. This is a tactic you can see on the tracks above (it worked for some and was no faster for others).

Nevertheless, Hilgenberg warns against generalisations. “It’s best not to work by averages. It depends on the weather the day you start and where you are starting from. And you should be prepared to stop, slow down and go south.”

This is one route where weather conditions can change quickly and up to date forecast information is invaluable. Many skippers make their own decisions after downloading GRIB files. Irishman Brian Linehan, sailing his 68ft Nordia ketch Asteroid with his wife Loretto, three of his five children and two friends, checked in with Herb Hilgenberg and also downloaded GRIBs from MailaSail (www.mailasail.com).

Linehan also notes that good, old-fashioned barometer observation is invaluable: “We recorded pressure every two hours to see where we were on the high pressure.”

Another popular paid-for option for Caribbean and North Atlantic weather is Chris Parker – www.caribwx.com

2. Adjust your watch system

You may need to alter your tried and test watchkeeping rota because of extra crew, variations in experience or the need to run two-person watches instead of single watches.

There are numerous possibiities. As night watches are colder and more tiring than people are used to, a good option if you have sufficient crew might be rolling watches. One example of this is three hours on, six off with a watch change every one-and-a-half hours, so you’re with one person for the first half of your watch and another for the second half.

“This really makes watches go faster and you always have one fresh crew, plus one that has already been on deck for half the watch and is familiar with what’s going on,” one rally skipper remarked.

If possible, share cooking and cleaning duties fairly. A good piece of advice offered is to display the watch roster so there are no disputes, and don’t be afraid to change things around at sea if it’s not working out.

Next page: clothing, cooking, spares and sails – what you need to know…