With water pouring in from an unknown source, the crew of the ARC yacht Magritte were rescued just before she sank, Skipper Steve Arnold tells Elaine Bunting the story

The boat, Magritte, a 44ft Moody Grenadier 134 ketch, was sailing along well in 15-20 knots of wind, under poled-out genoa and mizzen. The swell was 4-6m and Magritte was rolling along, and there had been nothing to suggest a problem. But when Arnold got up and lifted the sole boards he saw the water. “The bilges were fuller than I had ever seen them,” he says.

“I immediately figured it was a through-hull fitting. I had a diagram [of their location] at the chart table and we got it out and went through the boat turning them off,” he says.

He also made sure the bilge pumps were working and got the crew pumping out using the two manual pumps by the navstation and on deck. But it was soon clear that the level was not going down. Before long, he says: “I could see that the water was already a quarter of the way over the engine and about to start lapping over to the battery compartment.”

Crew training in the Solent before the off

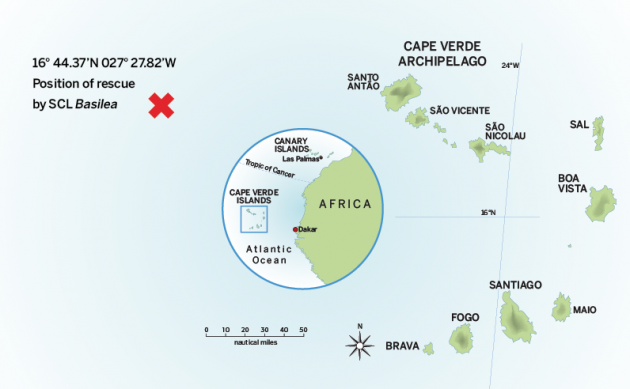

Steve Arnold and three crew – Teresa, his wife, Andy Mills and his daughter Georgia – were around 150 miles west of Mindelo in the Cape Verde Islands. They were taking part in the ARC transatlantic rally. This was the first part of a planned circumnavigation with the World ARC and a long-term dream of voyaging for the next ten years.

A new life afloat

Steve is an experienced offshore sailor. He took part in the 2004 Global Challenge ‘wrong way’ round the world race. “So I was quite prepared. That put me in a good position,” he says. Teresa, meanwhile, had done Tall Ships races and completed various sailing courses and together they looked for the right yacht to go round the world.

It took them two years to find Magritte. She was a solidly built, long-keeled, Giles-designed Moody with plenty of accommodation. The boat had been refitted for an RAF Yacht Club round the world rally in 2000, but hadn’t gone, “so it had everything on board that you’d ever dreamed of,” says Steve.

The Arnolds prepared the yacht at Shamrock Quay in Southampton. They had a surveyor examine every through- hull fitting. As a former engineer himself, Steve Arnold, took a technical view of the refit. “Every motor had a spare and there was a back-up to every back-up.”

They sailed straight to the Canary Islands with one other crew, a 12-day passage. It was their longest offshore voyage on the yacht and “the scariest thing we’d done,” says Steve. All was fine and on the first part of the ARC all went to plan until they had a crash gybe in windy, bumpy conditions around 400 miles out of Las Palmas. “It was at seven in the morning and I came up to see the pole smashing around,” describes Steve.

There was damage to the casting attaching the end of the kicker to the mast. “As we were close to the Cape Verdes and our watermaker was playing up – as usual – I decided to go in there. We got it fixed, and left a few days later.”

Magritte at the start of the ARC

It was just over a day out of Mindelo in Sao Vincente, when he was woken with the news that she was leaking.

Steve Arnold pushed the Mayday DSC button on his VHF radio before calling Mayday. As he waited for any reply, he got out his handheld Iridium phone and called Falmouth Coastguard. At one of World Cruising’s seminars before the start, skippers had been recommended to program in the number in case they needed to contact them to advise them of any safety situation aboard, although Steve had the number to hand anyway.

“It looked like we were sinking, it felt like we were sinking, but maybe a ship could give us a big pump and we could see the ingress. We had no idea where it was coming from; we couldn’t see. What I did know was that all power was going to go off at some stage.”

When MRCC Falmouth answered, Steve gave them a full description of the problem. “It was reassuring to speak to someone,” he says. But when Falmouth said they were going to pass on the distress to the nearest rescue co-ordination centre at Cape Verde, he admits: “I was a bit nervous about what they were going to do.”

Water kept on rising

Magritte’s crew turned the boat round, headed back towards Cape Verde and began climbing slowly back to windward under genoa. They followed all the advice they had learned from sea survival courses: they put on lifejackets, prepared the deck, got the liferaft ready, packed grab bags and secured them on deck and took seasickness tablets. Falmouth Coastguard had advised Steve to activate the EPIRB, which he did. They carried on bailing using all the pumps and buckets.

Within half an hour, a French yacht named Archibald II came up on the radio in response to the Mayday. They were not taking part in the ARC, but were on their way from the Cape Verdes to Martinique and were downwind of Magritte’s position. They told Steve they were turning around to sail back.

The water level continued to rise until it was sloshing over the sole boards, and starting to carry them and the contents around in a troubling mix. Steve Arnold recalls boards hitting his ankles as he walked below. He knew that once the water reached this level there could be twice as much in the boat as when he had seen in the bilges, as the volume of the hull increased so much at this point.

They could feel it in the sluggish movement of the boat. She became difficult to steer and keep wind in the sails and eventually became “completely unresponsive”.

Within an hour of the Mayday, MRCC Cape Verde made contact. They had asked for the assistance of any ship in the vicinity and at 1758UTC that evening had a reply from a Swiss-registered cargo ship en route from Brazil to Spain. SCL Basilea reported that they had altered course to go to the yacht’s assistance. They were 90 miles away.

Steve Arnold was told that there was ‘a rescue ship’ on the way. In his mind, he thought this meant a special rescue vessel based in Cape Verde. “I didn’t know it was a 12,000-tonne ship and that they had volunteered,” he says.

Several hours later at about 2200UTC Archibald II reached Magritte’s position. Steve phoned Falmouth Coastguard again and asked them what was the best thing to do: try to abandon to the other yacht or wait for the ‘rescue ship’. There were 4-6m seas, too rough to get alongside so to transfer the crew would have had to get into the water and by then it was a very dark, black night. “I didn’t want to do that,” says Steve.

The cabin with boards, cushions and stores floating near the companionway

“I was only 98 per cent certain the boat was going to sink and there was an actual rescue boat on the way.” Moreover, Archibald II had another week or two of downwind sailing ahead of them with limited space for four more people. Falmouth agreed they should wait. Archibald II’s skipper gallantly offered to stay with them until the ‘rescue ship’ arrived, and stood off astern.

Waiting in the dark

Over the next hour, during which Steve had no direct communication with SCL Basilea, the yacht’s power began to go off. Magritte had a bank of four new sealed 175amp batteries beneath the chart table and Steve reports that “every time I put my feet in the water I got a shock”. Things began to shut down one by one. The first to fail was the AIS, then the VHF radio. Steve remembers it was as much as half an hour after it was completely submerged that the main bilge pump eventually shorted out.

Lights went out until they were completely in the dark except for one light on the mizzen mast.

Steve kept in touch with Falmouth Coastguard regularly on his portable Iridium phone, but he heard nothing more from SCL Basilea and kept wondering why. “We had a very, very frustrating four- or five-hour wait when I wondered if I could call Falmouth again and ask ‘Are you sure?’.”

What they didn’t know was that the crew of SCL Basilea had made several attempts to contact Magritte, but been unable to raise her.

After spending a couple of long hours bailing with a bucket, Teresa helmed, Georgia sat on deck and later would play a search light on the foresail to illuminate the yacht. They made sure they kept busy with jobs, checking and rechecking things. By then the water was midway up the cabin and down below the cabins were awash with boards, cushion, stores and wallowing unstably. You can see this in the video online at yachtingworld.com/magritte.

Steve doesn’t recall feeling scared, only that they were “desperately trying to remember all the training and make sure we hadn’t forgotten anything. We had safety equipment coming out of our ears, Archibald II behind us, a rescue ship coming towards us. We were always trying to think of the next thing to do.”

See the video the crew took as the boat began to sink >

When SCL Basilea was around 25 miles away they picked up Archibald II on AIS. The ship’s crew had been busy preparing for rescue ops, readying the rescue boat and its equipment, liferings and firing lines, coiling down lines and monkey leaders. When that was done, the master, Lorincz Tamas, told the crew to take some rest.

At 2312 SCL Basilea raised Archibald II on VHF radio. Steve could hear part of the conversation and the information was relayed to him by Archibald. It was “a very big relief,” he says. He was still under the impression that this was a dedicated rescue vessel.

At 2334 SCL Basilea and Magritte finally made contact by VHF. When the 140m cargo ship was at a distance of three or four miles, Steve and his crew saw it appear and were very surprised. “We could see two big cranes on deck and it had more lights on than the Blackpool Illuminations,” he says.

At first the plan was that SCL Basilea would launch a rescue boat to take off the crew. The master even mentioned the possibility of towing the yacht. A rescue boat was launched at around 0100UTC. Steve describes it as “RIB-sized with an inboard engine”. This was “immediately overwhelmed”. The master’s statement (left) notes that the boat did not have enough power and started to drift aft. The attempt was abandoned and the boat was lifted up again.