Dropping a rudder

In 2015 Norwegian skipper Mikael Ryking and his crew on the 40ft race yacht Talanta (pictured, above) dropped a rudder during an Atlantic crossing. They were 800 miles from the Canary Islands under spinnaker in 13-16 knots when their windward rudder delaminated and split from the end of the stainless steel stock.

They took the tiller off, put an M8 screw in the top of the stock with a line attached to it, and then knocked the bolt out of the square rudder block, allowing the 30kg rudder to slide out of the hull. Before doing so they had also led a line from the transom round the leading edge of the rudder and back to the stern so that they could retrieve the damaged rudder after dropping it.

They then did the same thing with the good rudder before swapping it over. “It was simple, amazing actually. The worst part was taking the [good] rudder up in the waves,” commented Ryking.

Their swap worked until 200 miles from the Caribbean when the remaining rudder also delaminated, leaving a short stub, but they safely made landfall in St Lucia undercanvassed under jib and a small corner of the mainsail.

Building a jury rudder

This shows the repair to a More 55 that had hit a whale, detaching the blade from the stainless steel web. The crew took two sole boards, drilled and fixed them together with an aluminium hinge on the leading edge from a radar reflector (it looked like a part-opened book) and it was slid up the stock and stub and lashed in position.

The jury rudder blade being manoeuvred into position with lines fore and aft and a crewman diving beneath the hull

With the aluminium hinge forward the holes drilled in the trailing edge have ropes rove through them like shoelaces

A crewman closes the two parts of the blade by tightening it using bilge pump handles to make a Spanish windlass

The finished result, with a lacing of ropes and cable ties. It was inspected twice a day by a swimmer and it held for 2,000 miles!

Pesky problems

The risk of water and diesel contamination increases when sailing in warmer climates and while they can seem like comparatively small problems, the time and effort taken to fix them is definitely worth spending.

A water filtering system for tap water is a highly recommended addition for most bluewater cruisers. A run of coarse to fine reusable water purifiers, fitted in series to the hosepipe inlet should do the trick. Another thing I take these days is a supply of purifying tablets to chlorinate the water tanks should they start going green or become smelly.

I’ve used these as a primary water purifier on a more self-sufficient Pacific crossing. We could pick up jerrycans of water from waterfalls and taps ashore and purify then on the run back to the anchorage in the dinghy.

Diesel bug can be a problem once leaving colder waters so I always carrying additives to combat this, and take extra filters – you can never go wrong with lots of filters.

A squall on the horizon that is soon to overtake this yacht. These are common in the tradewinds. Photo: Paul Laurie

Storms and squalls

Among the idyllic days of balmy tradewinds sailing, there can occasionally be some tropical weather to keep sailors on their toes. Most feared are the tropical revolving storms (TRS), of which much attention is given in meteorology texts and reports.

But if you are sailing outside the hurricane or cyclone seasons you have a low likelihood of encountering a TRS. Note, I say low… In 2005 I encountered two named tropical storms in the Atlantic at the end of November. But what is much more likely, indeed almost a certainty, is encountering squalls. These are relatively small weather events, but they can leave a trail of destruction and ‘kitemares’ if not managed well.

Squalls bring you wind shifts, wind increases, wind decreases, rain, hail and everything in between. While I have found them a great source of extra breeze allowing faster progress when racing across the oceans and through the doldrums, when you are cruising they are really just an annoyance (unless you need a shower).

How much wind is inside the squall will depend on a few things. Rain coming from it will usually mean more wind and the height of the squall will also determine the likely increase in wind speed. One of the most useful strategies is to get to know the ‘height factor’ and use that to estimate the likely increase in wind. Once you have sailed cautiously through a few you will start to build a picture of what they are like.

The height factor is the number of times the sea-to-cloud base height fits inside the cloud. Usually squalls of 1 or 2 on the scale will give only a slight increase/puff of wind. Squalls of 6 or more get my full attention! Squalls with rain are easily trackable with radar and the more you understand them the better prepared you will be.

Lightning on the horizon. Note here that the helmsman is clipped on to the cockpit table. This is not recommended as it is unlikely to be designed as a life-carrying strong point. Photo: Tor Johnson

Lightning strikes

Sooner or later you will encounter lightning. It can strike in home waters as well as on bluewater routes. There is much debate about the best ways to protect your boat. There is also evidence that catamarans are more prone to strikes than monohulls.

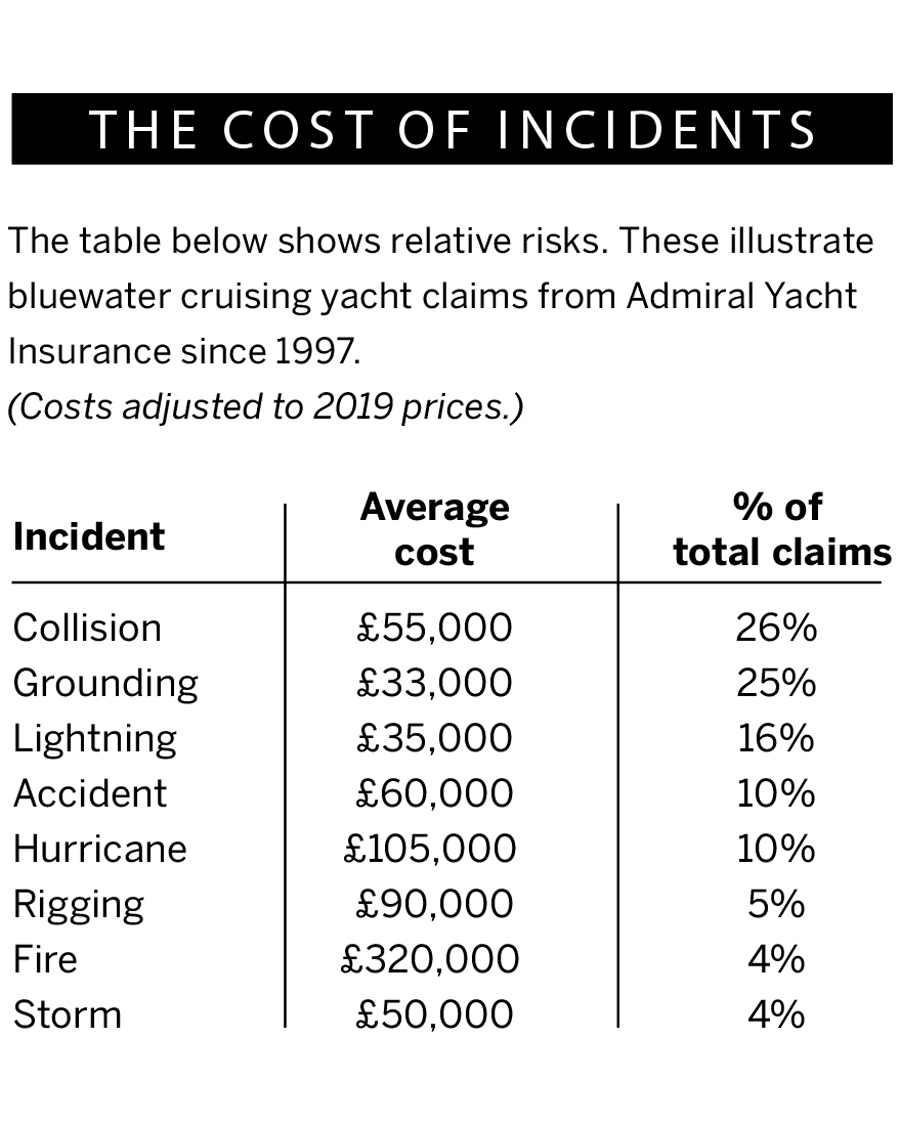

If lightning does reach your boat directly or indirectly through a nearby strike in the sea it’s likely to do serious damage. Admiral Yacht Insurance quotes the typical cost of a lightning damage claim at £35,000, and interestingly they have seen an increase in the frequency of claims over the last decade.

From personal and anecdotal evidence I feel it is definitely worth protecting your boat with solid lightning conductors to channel the lightning from the mast and rigging out through the keel. Lightning has been known to arc to metal through-hull fittings, causing skinning incidents. Lightning dissipators fitted to the masthead get mixed reviews, but they do bring me some comfort as I look up in the otherwise helpless situation of being in a lightning storm.

As a rule of thumb, power consumption for ocean cruising yachts is typically 20Ah per day for a 12V system

While on the Clipper Race, another yacht, Qingdao, was on the North Pacific crossing and lost all their electronic systems. They suspect the lightning strike came down the VHF wire, jumped across the AIS/instrument wires into the navigation PC and the main panel. There was a bang and plenty of smoke, and the deck was scorched near the chainplates. They finished the remaining three-week race to San Francisco with only a handheld GPS and didn’t do badly in the race.

There has been much discussion about the use of the ship’s oven as a Faraday cage to protect electronic equipment in an electrical storm. Interestingly Qingdao’s handheld GPS was in their grab bag and survived the strike, but if I had the time and forethought, I’d stash my spare electronics in the oven just in case.

Power problems

Power generation is a huge part of the planning for bluewater cruising. With so much kit on board there are likely to be problems. Indeed 5% of the fleet in the past two ARCs reported significant power and electrical equipment failures and nearly a third of the boats experience some sort of power or electrical problem.

Photo: Apex News & Pictures

Total power failure is not uncommon (again I have experienced this) and it can be precipitated by equipment malfunctions and failures as well as catastrophic issues such as lightning or fire. Much of onboard life demands power, from weather and comms to autopilots, freezers, watermakers, pumps and even some gas solenoids.

So how do you prepare for this? Most importantly, ensure you have enough water and a way of pumping it from tanks. As a guide, 300 litres is a typical consumption for two people making a modest 20-day ocean crossing with enough water for drinking (4l per person per day), washing (6l/day, so a quick rinse shower), cooking and rinsing dishes (5l/day). Consider additional supplies in case of slower progress or a tank leak.

If your satellite phone is built into the boat, you may want to consider a smaller handheld option with more flexible charging options, such as an Iridium GO! I have also used small independent solar chargers – these can be a good option but not fast. Then, if the lights do go out, you can just relish the opportunity to experience sailing as it used to be, in the days of the pioneers.

A direct hit

Lightning strikes accounted for €10m of claims in 2019 for yacht insurers Pantaenius, its third largest category by amount. High-risk areas include the Caribbean, Florida, and the Mexican Gulf, but “10-12% were in the Mediterranean, and that is coming from below 5% in the last decade”, comments MD Martin Baum.

Pantaenius puts this down to “the climatic situation, areas warming up more, but also yacht electronics are getting more complex.”

A yacht struck by lightning faces lengthy checks and repairs. A carbon mast will need to be unstepped and fully NDT tested, for example, and all wiring and electronics checked. Owners can easily lose a complete season’s sailing to repairs and bills can be huge. Repairs to a 112ft superyacht hit by lightning in Panama last year reached almost €800,000.

Pantaenius points to research that suggests catamarans are three times more likely to be hit, not only as they are over double the surface area of a monohull, but because of more difficulties with adequate grounding in the absence of a keel.

Pantaenius is considering introducing a double deductible on lightning risks for areas outside Europe unless yachts are fitted with lightning protection, and they are recommending an active system, such as the CMCE Sertec Elna, routinely used to protect airports, oil rigs and wind turbines.

About the author

About the author

Vicky Ellis is a Yachtmaster Instructor, an ARC safety inspector and a former professional sailor who skippered Switzerland in the 2013/4 Clipper Round the World Race. She now speaks on leadership and building high performance teams, and runs Cast off the Lines, preparing people for bluewater sailing.

First published in the March 2020 issue of Yachting World. In the April issue, out now, we look at rig failure and other common problems.

About the author

About the author